One life as Paris

Derek Robertson

It is not, in fact, difficult to like Paris Hilton.

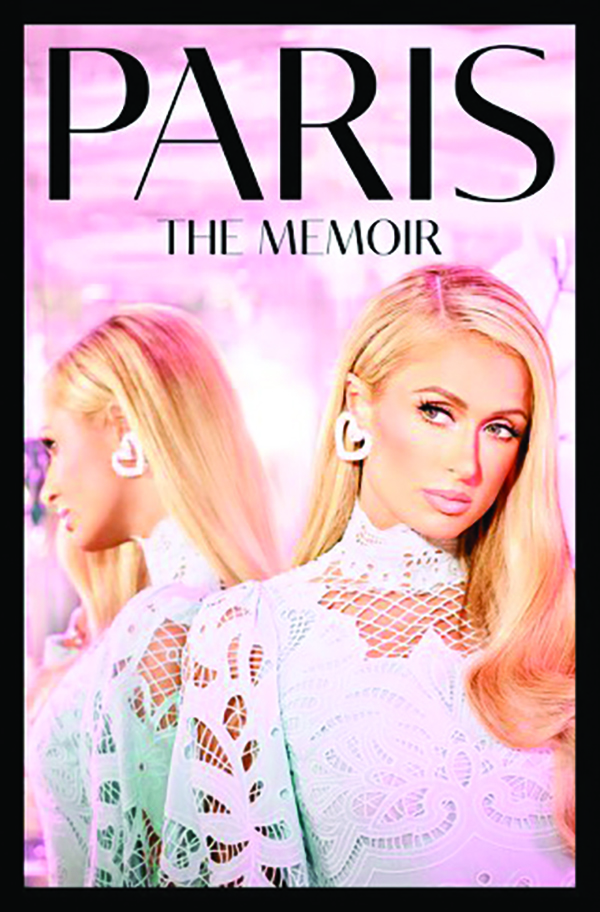

The mogul-heiress-reality television star’s mononymous Paris: The Memoir dropped last month into a cultural landscape thoroughly cratered with tell-alls from female celebrities of a similar vintage. They presume the opposite: that you, suffering a hangover from premodern, Letterman-like snark at best (and unreconstructed woman-hating at worst), harbor a perception of said women as any number of misogynistic epithets — strumpets, flibbertigibbets, sluts, whatever. Lucky for you, books such as Paris are here to help. With a bit of cultural reframing, you will realize the error of your ways and see them in their full humanity.

As strong of a case as there is for rethinking the noxious cultural assumptions of the Y2K era, Hilton provides a particularly tricky platform for doing so. At the dawn of the reality-television era, she was the embodiment of its flaws, evils, and cultural ill-omens: vapidity, unearned privilege, sheer bimbo-ness. At arguably the peak of their cultural influence, South Park creators Matt Stone and Trey Parker viciously parodied her in an episode titled “Stupid Spoiled Whore Video Playset,” in which she is depicted … in various ways unfit for description in a family magazine. John McCain depicted Barack Obama as a contemporary of her and Britney Spears in a 2008 ad. (This was not meant as a compliment.) MSNBC’s Mika Brzezinski refused to read news about her.

Which is why, if you haven’t kept up with her various adventures since roughly the time of the Great Recession, it might be surprising to read her memoir and realize that not only is it difficult to dislike her, it is nearly impossible. Credit, as you should, veteran ghostwriter Joni Rodgers, who keeps the pace lively and fills the book with a series of arresting turns of phrase. But the truly weird, singular personality on display in its pages, and refreshing lack of pretension or grievance, is a more powerful rebuttal to Hilton’s critics than you likely expect or have seen before.

The writerly collaboration bears fruit far more often than you’d expect: “The endless school day felt like being waterboarded with a vanilla milkshake.” There’s real introspection mixed in with the nearly pornographic depictions of wealth: “She sent a private jet loaded with food from Mr. Chow’s, a vivid demonstration of both the love of privilege and the privilege of love.” And when the prose turns solemn, it leaps out at you, turning you shamefaced like you’ve cracked open a junior high schooler’s diary: “We adored Princess Diana. Now she was in Heaven with Marilyn, forever young, forever perfect.” Describing Rene Magritte’s The Treachery of Images, she writes that the artist “wasn’t asking us to pretend the painting is a pipe; he was daring us to accept the smoking-hot realness of art.” Improbably, to read Paris: The Memoir is to erase any doubt that she ever considered another option.

The implicit promise of a memoir, whether it’s Hilton’s or Albert Speer’s, is to explain the why of it all. Hilton’s origin story, depicted first in the 2020 documentary This Is Paris, is undeniably tragic: Exhausted by her teenage 1990s New York City club-kid antics, Hilton’s famous parents shipped her off to a camp for troubled teenagers founded on the principles of the psychotic “therapy” cult Synanon. Horrific abuse, emotional, physical, and sexual, ensued. Hilton is now an advocate of strict oversight of such facilities, appearing on Capitol Hill to boost legislation as such alongside members of Congress, including Rep. Ro Khanna (D-CA).

The effect that Hilton describes this experience had on her is heartbreaking — and intuitive as her motivation. Having had her personality erased in what amounted to a North Korea-style work camp, she became determined to rebuild and sustain it on her terms. Reading about the experience itself is, somewhat ironically, one of the more dull parts of the memoir, as it recalls (tragically) countless previous tales of abuse. But it’s quite effective as an origin story, as well as an intriguing rejoinder to the totalizing view of “privilege” as a magical elixir that insures one against all sorrows. One could make a persuasive case that Hilton suffered precisely because of her privilege, having parents with both the means and motivation to ensure their embarrassing daughter vanished from sight until she became more pliable.

The overall arc of Hilton’s life and career, including the inevitable, gossipy details of her numerous scandals, sex and otherwise, are far less interesting than her fractured musings about life and art. Hilton opens the book with an ode to the psychiatrist Dr. Edward Hallowell, whose treatment for her ADHD she credits with helping her reframe the disorder as marking her “a primitive badass in a world of contemporary thinkers.” Amid a decadeslong increase in ADHD diagnoses, Hilton uses her experience with it as a sort of metafilter for the book’s narrative, which is littered with strange asides about The Shining, the Waldorf salad, and the ever-present club music that has powered her second-act career as a DJ.

Hilton has always envisioned herself, she describes, as part of an unbroken tradition of multihyphenate celebrity innovators that includes David Bowie, Andy Warhol, and Diane von Furstenberg. And yes, she knows what your retort will be: She doesn’t actually make anything. She’s “famous for being famous.” This is where it becomes clear Hilton is a savant as a cultural critic. She is all too aware of the act of creation involved in conjuring, in her words describing an early photo shoot, “freedom and fresh sexual energy with an undercurrent of bottled-up rage.” She doesn’t create anything? Manufacturing cultural iconography is as “real” in its impact as manufacturing bullets or Teslas, a conclusion that’s impossible to escape for anyone intent on taking culture seriously rather than as a junior partner to adult considerations.

Hilton makes the best case for her cultural reevaluation as such implicitly, not explicitly. She’s cultivated her image like a professional, yes. But the memoir is shot through with an impossible-to-fake naivete that, like her contemporary Kim Kardashian, goes a long way toward explaining the unshakable psychic bond between her and a legion of aspirational lower- and middle-class fans. She’s just like them — getting too wasted, filling her house with pets, watching Adam Sandler movies, and genuflecting to the holy trinity of Marilyn, Diana, and Audrey. Except, you know … she has money.

If those are the self-consciously “real” elements of the book, the artifice is just as important. Hilton’s description of her partnership with the photographer David LaChapelle is one of the most profound sections of the book, revealing how perfectly the two needed each other. Case in point: A 2000 issue of Vanity Fair featured LaChapelle’s photograph of a glammed-out Paris Hilton and her sister Nicky in front of a champagne-pink Rolls-Royce parked in front of an infamous La Cienega flophouse. It’s prophetic in its shovel-to-the-face lack of subtlety, hallucinatory color scheme, and edgy, ambivalent girl-power ethos. It was, as Hilton would say, the moment. His art-world savvy educated her in the raw power of her nascent image-construction project. Her feral, guileless excess fueled LaChapelle’s lifelong project to capture the tacky American sublime. DALL-E could never.

“The rise of selfie culture isn’t about vanity; it’s about women taking back control of our images — and our self-images. I don’t think that’s a bad thing,” she concludes after a long meditation on the painful life and abrupt death of print-era paparazzi culture. It’s a point that’s been made endlessly since Instagram’s birth in 2010, usually not as concisely. And it’s correct: However vapid, materialistic, or self-obsessed you might think Hilton’s artifice, there is no meaningful distinction between that artifice and her. More than femininity, sex, technology, or luxury, her project is a lifelong, self-conscious dare to accept, yes, the smoking-hot realness of art. Nothing more, nothing less.

Derek Robertson co-authors Politico’s Digital Future Daily newsletter and is a contributor to Politico Magazine.