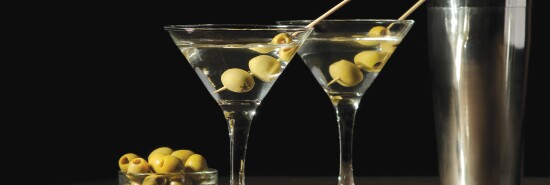

Is a martini better shaken or stirred?

Eric Felten

The answer just might be “neither.” That’s the lesson I learned when I ordered a house martini at Makoto, a small spot that was long the best and most formal Japanese restaurant in Washington, D.C. It was shuttered for a few years, but it reopened in March. Now focused on Wagyu beef, it is better than ever.

No small part of the restaurant’s recaptured success can be attributed to bar manager Corey Landolt. He isn’t the most likely mixer of drinks. For some 15 years, he was a featured dancer with the Washington Ballet, which is a good run given the notoriously short careers of dancers. All the while, he was learning a trade for his post-ballet life. “If I wasn’t performing on a weekend, I was bartending,” he says.

I recently went to Makoto and tried, not without a little skepticism, what was billed as a Japanese variation on the martini. The drink begins with an excellent Japanese gin — Roku, made by Suntory using a half-dozen botanicals found in Japan, including sakura flower and yuzu peel. Instead of vermouth, the Makoto bar combines the gin with a Japanese sochu distilled from barley. (It’s a brand called Mugi Hokka. If you can’t find it, try Fuyu sochu.)

But the technique that most matters is one that works whether making a traditional martini or the Japanese variation found at Makoto: making the drink cold without watering it down. Whether one shakes or stirs, the effort to make a martini sufficiently cold tends to overdilute the drink. That means, strictly speaking, there aren’t just two ingredients in the drink but three: first and foremost, gin; second, dry vermouth (of which there can be a little or a lot, to taste); and at last, there is the third liquid, the meltwater that comes from the ice in one’s beaker or shaker.

Martini exactitude has long been pursued. Pulitzer Prize-winning midcentury historian, speechwriter for Adlai Stevenson, Harper’s magazine columnist, anti-anti-communist, and martini devotee Bernard DeVoto was enough of a stickler that one could joke he demanded 1.845206 ounces of gin to half an ounce of vermouth. Even if one had the laboratory instruments necessary to measure out DeVoto’s preferred quantity, what about the water? DeVoto didn’t specify how much was preferable (or, from his likely point of view, tolerable).

What’s the right amount of dilution? How do you get it? These are questions that still bedevil because getting a properly arctic martini entails making trade-offs. Sure, the more one stirs or shakes, the colder the drink gets — but the more diluted it gets too.

Some strive to make martinis as cold as possible, and utterly undiluted, by keeping their gin in the freezer and their vermouth in the fridge. But that’s a mistake. Water is not something to be avoided in a martini; it is a subtle part of the finished drink, finishing what might otherwise be a harsh blast of hard liquor.

Which is where Landolt and his dancer’s precision comes into play. They’ve found the drink with 22% water added to the gin and sochu was better than the drink with 21% or 23%. In practice, that would mean combining two 750-milliliter bottles of gin with one 700-ml bottle of sochu. Calculate 22% of that 2.2 liter total and add exactly that much filtered water — 484 ml. Stir briefly and put it in the freezer for at least six hours.

The drink is ready straight from the icebox. Well, almost. Landolt pours the mix into a chilled cocktail glass and uses an eye-dropper to drip in exactly three drops of Japanese cocktail bitters. Garnish with a sprig of edible shiso flower on the rim, and this haiku of a precise cocktail has been achieved.

Eric Felten is the James Beard Award-winning author of How’s Your Drink?