The Met’s Champion succeeds as opera and woke agenda-setter

Jonathan S. Tobin

On the evening of March 24, 1962, a national television audience tuned into ABC’s prime-time program Fight of the Week for a championship bout held in New York’s Madison Square Garden. The fight was between welterweight champion Benny “Kid” Paret and Emile Griffith, the man from whom he had taken the title only six months before. It was the third fight between the pair inside of a year, and the quarrel between them had become personal due to Paret hurling the homophobic slur “maricon” at Griffith during the weigh-in earlier that day.

In the 12th round, Griffith, a native of St. Thomas in the U.S. Virgin Islands, backed the Cuban Paret into a corner. After initially stunning him with a blow that left him essentially defenseless and pinned against the ropes, Griffith landed 27 consecutive punches to the head until the referee belatedly pulled him away and ended the contest. Griffith’s flurry of punches, which were efficiently delivered in less than 30 seconds, can still shock those who watch the video on YouTube. Paret, who never regained consciousness, slipped into a coma. He lingered for 10 days before dying.

The horrifying spectacle set off a debate about boxing from which, despite the subsequent popularity of other fighters such as Muhammad Ali, it would never entirely recover, losing its perch as a mainstream national sport to become more of a niche entertainment.

Unlike the protagonist of the classic John Ford film The Quiet Man, in which a boxer played by John Wayne quits the sport and flees to his ancestral home in Ireland to find peace after killing a man in the ring, Griffith did not retire. Griffith expressed regret about Paret’s fate, but he had won back his championship when Paret fell. He kept at it for another 15 years, fighting 80 more times before being forced to quit at the age of 39 due to his declining skills. He died at the age of 75 in 2013 after suffering from the chronic traumatic encephalopathy that is an inescapable occupational hazard for boxers. During his life, Griffith was, for a time, the target for opprobrium in the press as a killer. But his day has finally arrived, albeit in quintessential 21st century fashion.

As a tragic victim who epitomizes the unhappy dilemma of closeted gay men in an era and a profession in which any hint of homosexuality was anathema, Griffith’s life is now seen as a metaphor for the casualties of the sports world’s alleged toxic masculinity. And that is the way he is depicted in the Terence Blanchard opera Champion, which had its long-awaited premiere this month at the Metropolitan Opera.

The staging of Champion at the Met is part of the transformation of the venerable institution. The post-pandemic priority of General Director Peter Gelb has been to change it from a storehouse of operatic masterpieces sung by the greatest singers in the world, its modus operandi for its first 138 years of existence, to a place where one is nearly as likely to hear contemporary pieces as classics, with the emphasis on those with minority and politically correct themes.

In the recently announced 2023-24 Met season, about a third of the announced performances will be recently written operas. Another feature of this season will be Blanchard’s Fire Shut Up in My Bones, an opera based on the memoir of New York Times columnist Charles M. Blow that opened the 2021-22 season. Still, unlike some of the other new works the Met has produced in the last two years, such as Matthew Aucoin’s miscalculated Eurydice, Brett Dean’s tedious Hamlet, or Kevin Puts’s star-studded but tendentious The Hours, Blanchard’s operas have much to recommend them. That’s true even if there’s little doubt that the main reason the Met chose them is political rather than musical, part of the company’s post-Black Lives Matter summer decision to, like so many other mainstream artistic institutions, hire a highly paid artistic commissar to police their hiring and repertory decisions.

The influence of Blanchard’s film and jazz work predominates more here than in Fire Shut Up in My Bones. It lacks the latter’s occasional soaring lyricism. But driven by its pervasive jazz rhythms and syncopation, it does move Griffith’s story, told in flashback with three singers depicting him at various stages of his life, along with dispatch, meanwhile integrating the use of dance numbers into the narrative in a more cohesive fashion. It’s never dull, which is a lot more than you can say for the operatic work of Aucoin, Dean, Puts, or even the far more celebrated Philip Glass.

Still, unlike Fire Shut Up in My Bones, which eschewed politics despite being inspired by the memoir of a leftist columnist, Champion is an opera with an agenda. It is driven by the need to portray Griffith, who was, at best, a morally ambiguous figure, as a victim-hero. Yet if Griffith is now remembered more for being the killer of Paret than as a six-time champion, the opera seeks to divert responsibility for that death in the ring elsewhere.

In some ways, Griffith was a victim. The opera depicts his conflicted introduction to New York’s gay bar scene as well as his brutal beating by thugs later in life, in which he nearly was killed after leaving such a hangout. “I kill a man, and the world forgives me,” librettist Michael Cristofer has him sing. “I love a man, and the world wants to kill me.”

Yet anyone who watches the video and sees the fury with which Griffith assailed his helpless opponent cannot entirely buy into an effort to make him, rather than Paret, the victim of the story of their fight. Still, in keeping with its desire to elevate Griffith as a martyr to homophobia, the opera also chooses to demonize Paret as a homophobic villain, exaggerating his pre-fight insult into a lengthy scene of histrionics rather than a singular, if still hurtful, act of pre-fight trash talking. The slain fighter knew no English and was himself likely also the object of racist insults, also leaving behind an impoverished widow and infant child. Even Paret’s ghost, who haunts a dementia-racked Griffith, is portrayed as a vulgar lout, robbed of his dignity even in death. The fight was a battle between two black immigrants, each with their own reasons both to embrace and to lament the sport that lionized them. But here, Griffith is made to be a stand-in for the plight of gay men in a straight world.

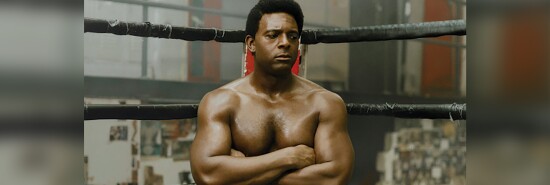

Though it is handicapped by a didactic approach, Champion still succeeds musically thanks to the work of Met Music Director Yannick Nezet-Seguin. The opera provides some outstanding opportunities for its singers. The wonderful soprano Latonia Moore, who plays Griffith’s outrageous mother, Emelda, steals the show in much the same way she did in Blanchard’s Fire Shut Up in My Bones with fabulous vocalism and a saucy stage presence. Veteran Met bass Eric Owens provides a depiction of the boxer’s dementia-driven confusion that is deeply affecting. Still, the show belongs as much to bass-baritone Ryan Speedo Greene, who plays boxing-aged Griffith, as to Blanchard. Looking every inch the boxer onstage, he sings commandingly and carries much of the drama.

Blanchard’s works might not have gotten a hearing at the Metropolitan Opera that was — a place where, not that long ago, only the greatest examples of the genre and near-masterpieces had a chance to be staged. While other contemporary composers have a more classical technique, Blanchard seems to grasp something they do not. No matter what century it was written in, an opera is musical theater. An opera can only succeed if it tells a story with music in a manner that is compelling to audiences. Neither Fire Shut Up in My Bones nor Champion is close to being on the level of the classics of the standard repertory, but they at least accomplish that much. They are worth an operagoer’s time.

Jonathan S. Tobin is editor-in-chief of JNS.org and a columnist for Newsweek. Follow him on Twitter at: @jonathans_tobin.