A home turf for great movies

Daniel Ross Goodman

On weekends in college, I would go to the local movie rental store to take out a few stacks of popular recent movies, making my way through some of the modern American classics. It wasn’t until I saw The Lives of Others at Lincoln Plaza Cinemas in the winter of 2007 that I became what you could call a certified cinephile. The Lives of Others is a transcendent German film about love, writing, and espionage set in East Berlin. It won the Oscar for Best Foreign Film at the 2007 Academy Awards, and it is one of those haunting movies that stays with you forever. It is also the kind of movie that is rarely screened these days in mainstream cinemas.

If it were released today, it would likely be available only on some streaming service, without ever having the opportunity to spark a love for cinema. But I had the fortune of coming of age before the dawn of the streaming takeover of the movies. And I had the fortune of living in New York City when Lincoln Plaza Cinemas was still in existence.

If you speak to enough New York movie lovers, you’re likely to find a good number with a similar story — a story about how one special movie in one special theater made them fall in love. And for many of these New York movie lovers, that theater was very likely Lincoln Plaza Cinemas. Located a few blocks away from the New York Philharmonic, the Metropolitan Opera, and the New York Ballet, it was the film equivalent for what those great New York institutions represent for music, opera, and ballet. I saw some of my favorite movies of all time, including No Country For Old Men (2007) and Midnight in Paris (2011), in this humble, poorly lit, basement-level theater, as well as the film that gave me my start as a movie critic — Terrence Malick’s 2011 masterpiece The Tree of Life. Like many New York movie lovers, I especially looked forward to Oscar season every fall and winter at Lincoln Plaza Cinemas, when the theater would release its latest batch of films that were sure to garner Academy Award nominations.

There was a time you might suspect you’d be in a screening with a famous movie critic and a later-to-be-famous movie critic if you went there during the right season, to the right screening. But, in truth, you could find good films playing at Lincoln Plaza Cinemas at any time of year. Lincoln Plaza Cinemas was an integral part of New York film culture.

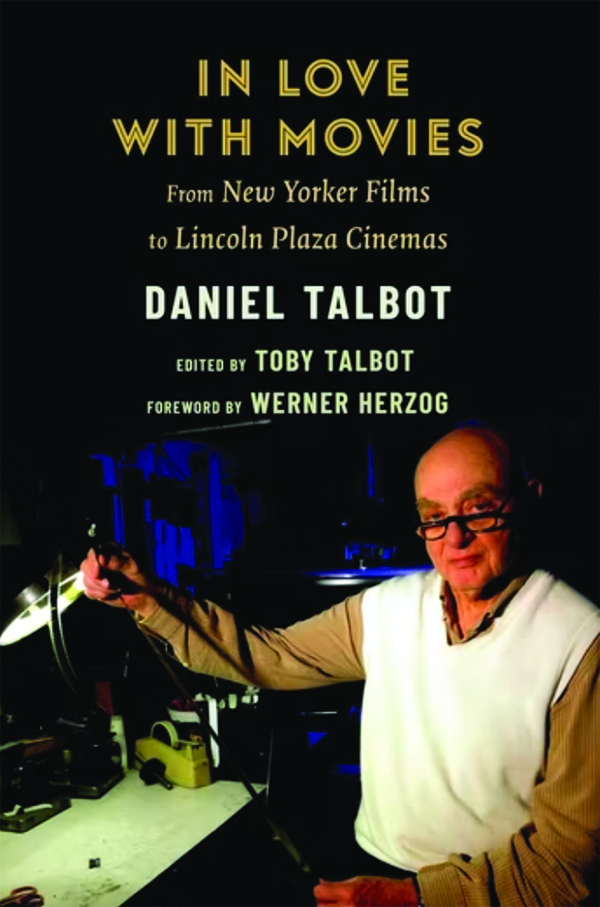

To the great sadness of so many of us New York movie lovers, Lincoln Plaza Cinemas closed in 2018 due to its landlord’s unwillingness to renew the lease. Lovers of the theater banded together and reopened it as New Plaza Cinema. Since 2018, that theater has wandered through the Upper West Side like Adam and Eve after they were expelled from the Garden, bouncing around from block to block until settling recently at the Church of St. Paul and St. Andrew on West 86th Street. But the cinema now comprises only one 74-seat theater, a far cry from Lincoln Plaza Cinemas’s six theaters of over one thousand seats and its simultaneously aspirational and cozy art-house ambiance. That cinema, like the delights of Eden, now lives on only in our collective memories. And it also lives in the wonderful new book In Love With Movies by the impresario of Lincoln Plaza Cinemas Daniel Talbot.

In Love With Movies is Talbot’s memoir from a career and a lifetime devoted to film. Talbot grew up in the Bronx during the Depression going to movies all day on Saturdays in an era when it was still not unusual to go to the movie theater in a suit and tie. Naturally, when he was dating Toby Tolpen, the woman who would eventually become his wife, he took her to the movies with him. They married in 1951 and settled in Sunnyside, Queens, within walking distance of Manhattan. Talbot first worked in publishing as a copy editor of suspense novels, where he published what he believed to be the first ever highbrow anthology on film in 1959. At that time, he was also writing film criticism for Progressive magazine.

Soon thereafter, he became manager of the New Yorker Theater, the Upper West Side forerunner to Lincoln Plaza Cinemas. The roster of people Talbot recruited to help him run the theater is a veritable who’s who list of young film and literature Turks on their ascent. When he first started out as program director of the theater, he got some tips from Pauline Kael, who would later become a legendary film critic and who was then running a small theater in Berkeley, California. He brought in Peter Bogdanovich, who would also later become an important critic and director, to run a Forgotten Films series. He brought in Jack Kerouac, whom Talbot knew before the Beat writer made it big with On the Road, to write program notes for the theater’s Monday Night Classics series’ screening of F. W. Murnau’s Nosferatu. “He came to the screening smashed, already an alcoholic,” Talbot recalls. And Andrew Sarris, another young movie aficionado also on his way toward becoming an influential film critic, did notes for the theater’s screenings of Alfred Hitchcock’s The 39 Steps and Foreign Correspondent.

Talbot ran the New Yorker Theater until 1973, and Lincoln Plaza Cinemas beginning in 1981. In Love With Movies is not a comprehensive history of either theater but a selective one. Through the book, we get a sense of how important these cinemas were not only to New York cinephiles but to America’s world of film as well. This was mostly due to Talbot’s becoming not only a capable movie theater manager but an influential film distributor. Talbot championed Robert Bresson’s work at a time when the French director was having trouble getting his films shown in the U.S. He was instrumental in increasing awareness of auteurs such as Bernardo Bertolucci, Roberto Rossellini, and Yasujiro Ozu in the U.S. Many of the films that Talbot chose to distribute and screen at the New Yorker Theater and Lincoln Plaza Cinemas would then be screened at art-house cinemas in Boston, Philadelphia, San Francisco, and Los Angeles. He was almost single-handedly responsible for the success of Louis Malle’s My Dinner With Andre (1981), convincing Malle to film Wallace Shawn’s quirky script and then developing a plan to distribute and promote it. My Dinner With Andre is now regarded as one of the touchstones of the independent film movement. Talbot had a hand in the success of many other independent films and filmmakers in the U.S., so much so that in 1991, he was honored at Cannes for his film distribution work.

In Love With Movies is almost as pleasurable to read as seeing some of these great films themselves. Talbot’s writing flows freely and easily and is filled with light, comedic touches. It is also suffused with entertaining anecdotes about directors with whom he had personal relationships, such as Werner Herzog, who wrote the book’s foreword, and enlightening apercus about how to run a successful art-house theater and how to know when a film will be a hit — you should be able to tell that “something ineffable and unexplainable exists within the film.” Perhaps his most important observation is that we would be better off without the distinction between “art house” cinema and “mainstream” movies altogether. After all, “Should we say that John Ford or Alfred Hitchcock, Orson Welles, John Huston, Preston Sturges, or Martin Scorsese didn’t make ‘art films’? The term came about because many Americans have a foggy notion that only Europeans and Japanese are capable of making artistic films while Americans make only… well, what? Crap?”

Daniel Ross Goodman is a Washington Examiner contributing writer and the author of Somewhere Over the Rainbow: Wonder and Religion in American Cinema and the novel A Single Life.