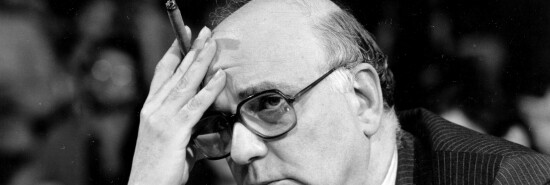

Jerome Powell’s Paul Volcker moment?

Tiana Lowe

Video Embed

As the saying goes, the Federal Reserve usually raises interest rates until something breaks. After one year and 450 basis points of tightening, something has finally broken.

Despite the federal government’s bailout of Silicon Valley Bank depositors, which Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen asserted was done to minimize the risk of financial contagion, investors are clamoring for the Fed to halt monetary tightening.

HOW BIDEN IS WORSENING THE LABOR SHORTAGE AND INFLATION

Since securing his confirmation to a second term as Fed chairman from the Democratic-controlled Senate, Jerome Powell has rebuffed investor demands, repeatedly reasserting and then following through not just on interest rate hikes but also on offloading the Fed’s balance sheet. But his resolve to refuse to finance the federal government’s spending spree has persisted so far in a period when raising rates has been relatively easy. Now, with Wall Street worrying that SVB was merely the first domino to fall, Powell must prove if he is the man for the moment, a worthy successor to his great idol, Paul Volcker.

Over at Bloomberg, economic historian Niall Ferguson expounds at length on the lessons from past banking crises, comparing the courage and integrity of Volcker’s commitment to crushing inflation to Arthur Burns, whom President Richard Nixon specifically appointed to keep the price of borrowing cheap and secure his reelection.

Burns’s bailout of the Bank of the Commonwealth “occurred between the 1969-70 and the 1973-75 recessions, at a time when inflationary pressures appeared to be abating,” Ferguson wrote. “Consumer price inflation (seasonally adjusted) had come down from a high of 6.4% in February 1970 to below 3.3% at the end of 1971. Although inflation rose back to nearly 3.8% in February 1972, however, the Burns Fed held the discount rate steady at 4.5%, down from 5% in October 1971. The rate remained there throughout 1972, even as inflation began to pick up in the second half of the year. Measured by the federal funds effective rate, monetary policy eased significantly in January and February 1972. By the end of 1973 inflation was at 9%.”

It is, or at least should be, easy to raise rates while the economy is still roaring. It is much harder to stomach the political pain and Wall Street wailing when raising rates after a financial break sparks investor panic. But as in 1984, when Volcker did what was right, raising rates even after bailing out Continental Illinois, Powell should not prioritize financial stability over his legal mandate to restore price stability.

The easiest way to square the circle is, after his show of flexibility both in the SVB depositor bailout and in liquidity swaps to other central banks, to go forward with a 50 basis point hike this Wednesday.

CPI inflation came in at 6% for February, three times the Fed’s inflation target. Core PCE, the Fed’s preferred inflation measure, actually rose last month. Real interest rates only just became positive, and that was in part due to quantitative tightening, half of which the Fed undid last week.

Raising interest rates while expanding its balance sheet may sound a bit like pressing the gas pedal and the brake at the same time. But in effect, that would allow Powell to pursue financial stability, mitigating the risk of further bank runs and collapses, at the same time as price stability. SVB was unique in how great a share of its assets was invested in Treasurys, so the rest of the big banks are at much lower risk of collapsing as the Fed continues to increase interest rates and thus depress the value of old low-interest government bonds.

Is it politically possible for Powell to pull this off? Not that Powell should care, but recall that President Ronald Reagan won 49 states during his 1984 reelection, in which Volcker had interest rates at 9% while inflation was 4%.

The markets are melting down over interest rates that have not yet hit 5%. If Powell wants to prove that the Fed stands independent from both the White House and Wall Street, he will see the job through.