Bill Nighy’s triumph

Graham Hillard

Living, the new film from South African director Oliver Hermanus, works a strange and leisurely magic. A seeming examination of bureaucratic inertia in 1950s London, it blossoms into a meditation on death, kinship, and what it means to leave a legacy. Though largely marketed on the strength of its 73-year-old star’s career-capping performance, the picture is far more than an individual exhibition designed to garner praise for its leading man. It is instead a small but potent miracle: a film that takes on our biggest subjects, risks sentimentality, but emerges with a clear-eyed vision of how even a wasted life can be restored to purpose.

The movie stars Bill Nighy as Rodney Williams, a senior functionary in a sclerotic and overmanned public works department. There, surrounded by files stacked precariously into “skyscrapers,” Williams and his team feign effort while doing their best to lose every jurisdictional fight that arises. Among the film’s most discouraging images is a shot of our hero depositing paperwork into what is essentially a garbage can. That each of the files thus misdirected contains a reasonable constituent request is obvious to all. Just as plain, however, is Williams’s utter disinterest in cutting through the red tape with which County Hall is evidently bound.

Closely adapted from Ikiru, Akira Kurosawa’s 1952 masterpiece, Living owes a secondhand debt to the 19th-century novella from which the Japanese auteur drew inspiration. Like Leo Tolstoy’s The Death of Ivan Ilyich, both Kurosawa and Hermanus equate bureaucratic paralysis with a kind of cancer of the soul. Following the novella further, the two pictures give physical form to this spiritual malignancy, chastening their protagonists with terminal diseases that bring about a period of much-needed self-reflection.

In Living’s case, this alteration in our hero’s circumstances occurs relatively early in the film with a doctor’s visit that begins with bad news and ends in grim silence. Shaken by his prognosis and determined to find a sense of meaning before he dies, Williams turns first to the pleasures of the flesh, accompanying an insomniac writer (Tom Burke) to both a peep show and a seedy pub. Though the latter scene gives rise to one of the movie’s loveliest moments, in which Williams sings a mournful Scottish ballad to transported onlookers, enlightenment clearly lies elsewhere. Borrowing again from its source texts, Living has in mind a humanistic solution to the problem of mortality. Williams must journey further if he means to uncover it.

Like most episodic films, Hermanus’s picture depends heavily on the skill of the supporting players its protagonist encounters. As Williams’s grasping son, Michael, actor Barney Fishwick brings a poignant awkwardness to the proceedings as the two men struggle to communicate freely with one another. Also effective is stage performer Alex Sharp as Peter Wakeling, a naive young man who is only just beginning his career in the civil service. Yet highest honors in this class go to Aimee Lou Wood, the breakout star of Netflix’s better-than-it-sounds Sex Education. Wood plays Margaret Harris, a sweet-tempered ingenue with whom Williams works and eventually forms a platonic connection. It is in her restrained but indisputable liveliness that we see the joie de vivre that Williams would like, however briefly, to recapture.

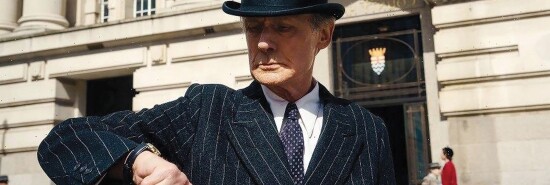

Whatever the talent of its ensemble, Living would go nowhere were it not for the superb and quietly astonishing performance of Nighy in the lead. The veteran actor has been good before, of course, in such films as Love Actually (2003) and Notes On a Scandal (2006). Nevertheless, this latest work represents the pinnacle of his screen career. A model of muted pain and yearning, Nighy dominates the film from start to finish, pronouncing, with his soft tenor voice, the official evasions and increasingly personal longings that mark his character’s progress. To see Nighy onscreen is to forget altogether that acting is being done, so effortlessly naturalistic is his manner. As I write these words, Brendan Fraser has just won the best actor Oscar for The Whale, a performance that required little more than makeup and a fat suit. The word “travesty” hardly does justice to the error.

As for the canvas on which Nighy paints, it is exceptionally well crafted by Hermanus and screenwriter Kazuo Ishiguro. The director, previously of minor South African art films, Hermanus labors here with unobtrusive confidence, allowing his department heads (especially art director Adam Marshall) to shine. Hermanus’s single trick, a title sequence presented in vintage Technicolor, provides a clever introduction to midcentury London. But note, too, the movie’s pitch-perfect locations and design: not only Williams’s beautifully labyrinthine office but an unrepaired East End bomb site that plays an important role in the film’s resolution.

What that role happens to be, I won’t reveal, even though Kurosawa fans know the answer already. Suffice it to say that Living’s Nobel laureate-produced screenplay does its job with intelligence and grace. From Williams’s post-diagnosis desolation to his final life-affirming act of virtue runs a circuitous but entirely navigable path. We believe and understand not only our protagonist’s wretchedness but the epiphany that allows him, at long last, to change.

The sum of these parts is a film that is not merely superlative but deeply moral, a judgment I haven’t had occasion to make since 2021’s already forgotten jewel, The Green Knight. Is it any accident that both pictures have their roots in great literature? I can’t be trusted to answer. Ask someone who was never an English professor.

Graham Hillard is the author of Wolf Intervals (Poiema Poetry Series) and a Washington Examiner magazine contributing writer.