The mysterious death of Edgar Allan Poe

Diane Scharper

In June 1849, when Edgar Allan Poe was 40 years old, he left his mother-in-law and aunt, Maria Clemm, in their New York home to go on a lecture tour. He planned to raise money to start his own literary magazine. It had been a stressful couple of years since his wife, Virginia, died from tuberculosis. Now, his fortune was improving. He told Clemm he would return “to love and comfort her” and not to worry about “her Eddie.” But she never saw him again.

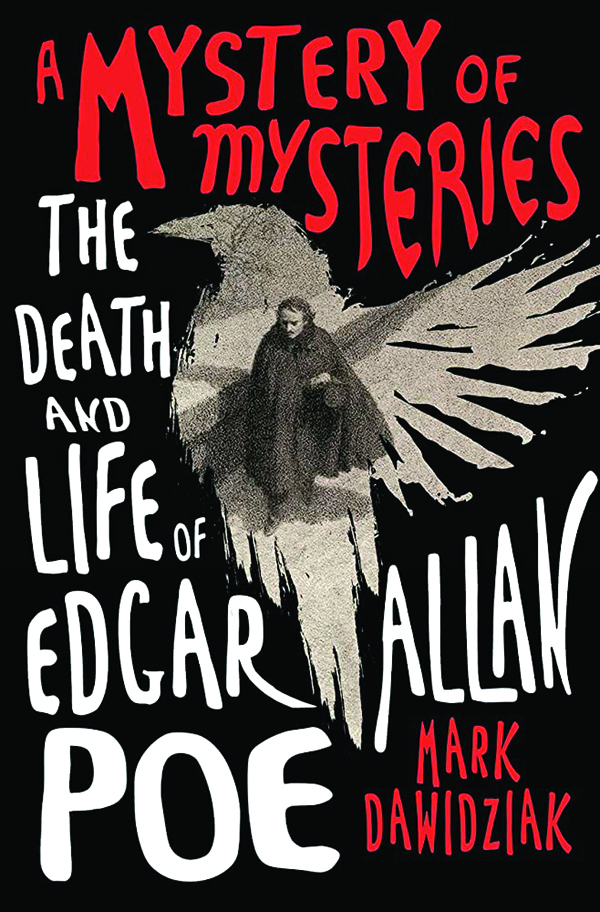

Poe is the 19th-century author of works including “The Raven,” “The Black Cat,” and “The Purloined Letter.” Although some readers conflate Poe with his frenetic narrators, Mark Dawidziak’s biography, A Mystery of Mysteries, argues that, unlike some of his characters, Poe was not irrational. He would spend weeks conscientiously revising his work to create unhinged characters or to achieve a single effect in a story or a poem that he said should ideally be read in one sitting.

Poe was respected as an editor and a critic, and he was one of the first to try to earn a living through his writing. An outspoken critic, Poe had enemies, but he also had illustrious friends, such as Nathaniel Hawthorne, who recognized Poe’s genius and praised the force and originality of his work. Charles Dickens helped Poe become known in England and Europe. It is believed that Dickens’s raven, Grip, was the inspiration for Poe’s “The Raven,” and Dickens’s “The Chimes” inspired Poe’s “The Bells.”

In addition to numerous stories and poems, Poe wrote nearly 1,000 essays, reviews, articles, columns, and critical notices. He reviewed books and served in an editorial capacity for several highly regarded magazines, newspapers, and annuals such as the Southern Literary Messenger and the Broadway Journal. In his reviews, he pointed out grammatical errors and exposed shoddy thinking. Insisting that American writers meet high standards, he slammed those who did not.

Poe died in Baltimore a few months after he left Clemm. No one knows what killed him. Some suspected suicide. But according to Dawidziak, suicide is unlikely since Poe was optimistic about the future. Others suspected illness. Poe had become engaged to Sarah Royster Shelton in Richmond at the end of September 1849, about two weeks before he died. Shelton was concerned about Poe traveling to Baltimore because he had a fever and seemed ill.

After six days when his whereabouts were unknown, Poe collapsed on a rainy Oct. 3, delirious and seemingly drunk outside Gunner’s Hall, a Baltimore tavern and polling place. On Oct. 7, he died at Washington College Hospital, where attending physician Dr. John Moran made a record of his symptoms and several years later created another record that contradicted the first.

Poe suffered two deaths, as Dawidziak sees it: a physical death as well as the death of his reputation as a great writer. Pop culture merchandised him as a psychotic with a witchy face on items such as refrigerator magnets, T-shirts, coffee cups, and even socks.

Dawidziak hopes his biography will find the genuine Poe behind the hype and acquaint 21st-century readers with Poe, the professional writer, loving husband to his wife, Virginia, and devoted son-in-law to Maria Clemm.

Poe had a hard life. His father abandoned Poe’s mother, Eliza, and his older brother, Henry, and younger sister, Rosalie. Soon afterward, Eliza died from tuberculosis, and the children were placed in foster families. Poe did not get along with his foster father but loved his foster mother, Frances, who died of tuberculosis. Poe dropped out of the University of Virginia and later West Point because of money and drinking problems. He married his 13-year-old cousin who, several years later, also died of tuberculosis, as did Poe’s brother, Henry. Poe could never make sufficient money from his literary career to provide a comfortable living for his wife and her mother. His money troubles may have been partly due to his penchant for alcohol.

But, according to Poe experts, we don’t know how severe his alcohol problem was. Some experts say Poe had hypoglycemia, and a small amount of alcohol could intoxicate him. Others, pointing to Poe’s productivity, say that Poe’s drunkenness is exaggerated. Still others say that substance abuse hung over his adult life like a curse.

Dawidziak refers to the views of about 50 Poe authorities from Dr. Moran to Patrick Hansman, a forensic psychologist, to J. Gerald Kennedy, Poe biographer, to actor Vincent Price and author Stephen King. Physicians, museum directors, historians, academics, and writers share their theories concerning Poe’s demise. They range from cholera to alcoholism, drugs, latent tuberculosis, rabies, robbery, a brain tumor, and an illegal voting practice called cooping.

Dawidziak structures his text in parallel timelines, with chapters covering the last three months before his death alternating with earlier periods. The method seems unnecessarily difficult to follow, but at book’s end, everything comes together. A timeline would help.

Dawidziak believes that without additional evidence such as exhuming Poe’s body and finding “a hatchet sticking out of his back,” his death will remain a mystery. But Dawidziak has some interesting speculations.

Cooping is one of them. Election irregularities were rife in Baltimore (nicknamed Mobtown), and cooping was a popular method of ensuring a win by one’s desired candidate. Thugs kidnapped their victim, plied him with alcohol and drugs, moved him from polling place to polling place, and forced him to vote for their political choice.

Rabies is a less probable theory of death. There were no leash laws, and dogs roamed Baltimore city streets in 1849. No rabies vaccines existed, and rabies was prevalent. But Poe did not have hydrophobia (a sign of rabies) as some had suggested.

Dawidziak nods to John Evangelist Walsh’s theory (from Midnight Dreary, The Mysterious Death of Edgar Allan Poe) that Sarah Royster Shelton’s brothers followed Poe to Baltimore and beat him nearly to death because they disapproved of her planned marriage with Poe — which convinced me.

After Poe’s death, the Rev. Rufus Griswold and other literary enemies attacked Poe’s reputation. Griswold objected to Poe’s drinking and the immoral content in his stories. He also wanted revenge for Poe’s negative reviews. Writing Poe’s obituary for the New York Tribune, Griswold began, “Edgar Allan Poe is dead…. This announcement will startle many, but few will be grieved by it.”

There were some who were not grieved. These included American writers such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, who referred to Poe as The Jingle Man. Poe, however, disdained the Transcendentalists and called them Frogpondians, a jab at their croaking moralism.

Most European writers admired Poe. French poets, such as Charles Baudelaire, claimed Poe was a genius and that Americans were not capable of appreciating him.

Today, most Americans respect Poe as the father of detective fiction and one who raised the genre to the level of literature. They see him as an early modernist with a talent for understanding the human psyche. This is in part due to efforts by scholars such as Dawidziak, who convincingly argue that the closer one looks into Poe’s death, the more he comes alive.

Diane Scharper is a poet and critic who teaches the Memoir Seminar for the Johns Hopkins University Osher Program.