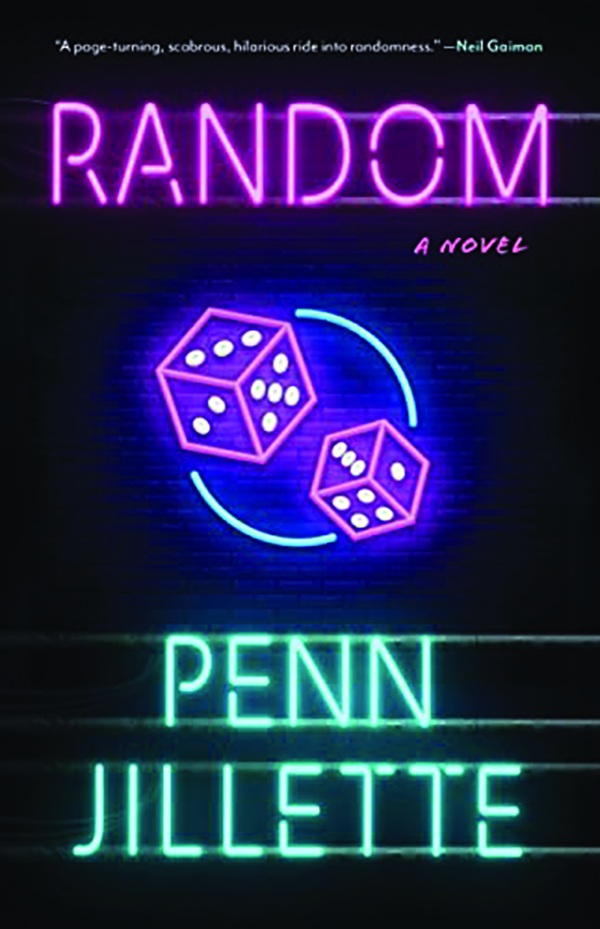

America’s top magician writes a novel

Jacob Grier

Magicians don’t like leaving things to chance. Even when a performance seems casual and impromptu, their tricks are carefully planned and under control. Chance can make a trick go wrong. Sometimes, it’s just a card trick; sometimes, it’s a matter of life and death. A handful of magicians have died performing the bullet catch, a trick in which they appear to catch a bullet in their teeth. The illusion is a signature showpiece for the magical duo Penn and Teller, both of whom are still among the living.

At a recent book talk in Portland, Oregon, Penn Jillette credited this to careful planning. For this trick in particular, he says, his stage staff is instructed to halt the show immediately if he or Teller deviates even slightly from the script and choreography. It’s a point of pride for him that in decades of Penn and Teller performances, no one has ended up seriously injured.

Jillette’s new novel Random, written during a pandemic-induced break from performing, took him into the head of a character who has a very different relationship to chance, one that he finds a bit scary. The unlikely protagonist is Bobby Ingersoll, a 20-year-old nobody who drives a billboard truck up and down the Las Vegas Strip advertising live nude dancing girls. This is a good enough gig for Bobby until his deadbeat father’s massive gambling debts come due, putting him in the sights of a very bad dude who’s going to murder his whole family if they don’t pay up.

Bobby has no money and no realistic way of coming up with the 2 1/2 million dollars he needs to keep his family alive. His only hope is chance. Luckily, he’s in Vegas, where opportunities to take a chance abound. Recounting exactly what happens next would spoil the immense fun of reading the book. Suffice it to say that the unlikely events that unfold transform Bobby’s life. He becomes a disciple of random, leaving his decisions henceforth to rolls of the dice.

As Jillette explains in the preface, “Completely committing to random would be a superpower.” If you’re acting strategically, someone might outsmart you. But no one can outsmart you if you’re acting at random. An additional aspect of the theory: “Committing to and acting with passion on a decision are often more important than which decision is made.” Imagine if Hamlet simply rolled the dice on whether to avenge his father’s death in Act One. The play would be a lot shorter, and less of the cast would end up dead.

Bobby becomes the anti-Hamlet. Whenever the slightest doubt creeps in, he consults his dice and commits fully to the decision they make for him. It can be a small thing, such as which drink to order at Starbucks. Or it can be something big, such as spontaneously becoming a private investigator. This takes the plot in some weird directions and confuses the hell out of Bobby’s antagonists. Some threads lead nowhere, while others end up intricately, improbably connected. Think Dog of the South meets Seinfeld. Jillette’s yarn is absurd, eccentric, and very funny.

I should mention that it is also very, very raunchy. As one might expect from a Penn Jillette hero, Bobby Ingersoll is good-hearted but not hung up on religion or sexual mores. Fifty pages in, I was emailing my editor to ask our policy on printing a slang phrase for a towel used to wipe up ejaculate because the prop was referenced gratuitously often in the text. Sex and bodily fluids crop up as frequently in Random as they do in real-life Vegas hotel rooms. Be warned, and maybe don’t pick this for your church book club.

Yet behind all the sex, violence, and ridiculous situations is a potentially seductive way to live. Like in an election or a sports match, whenever we make a decision, only one part of us wins. “We all contain multitudes but winner takes all, and real desires are just ignored and eventually forgotten,” Jillette narrates as Bobby’s new life philosophy crystallizes. “Random could shake things up a bit. He would let the sincere parts of him, sincere desires and actions, happen, even though they wouldn’t otherwise cross the threshold to win. Random would make him completely himself.”

Despite the title, the possibilities assigned to the dice aren’t truly random; they’re all options that at least some part of Bobby’s psyche finds appealing. Rolling a pair of dice offers 11 different outcomes across a bell curve of probabilities. A seven is more likely than a two or a 12, so he can stack the odds. You can too if you want to try it. You’re pretty sure you want a beach vacation in Hawaii? Assign that three through 11. But a small part of you wants to try clubbing in Berlin? Give that two and 12. Roll the dice. You’ll probably end up sipping pina coladas, but just maybe, you end up in black leather at Berghain.

Is this a good way to live? Jillette traces the idea to a satirical 1971 novel called The Dice Man, which he was introduced to 30 years ago by a show business associate. Neither of them liked the book, but both found the idea intriguing. The associate had, in fact, used it to turn her life around, emerging from a period of paralyzing trauma by committing to following the dice. The dice enabled her to act when she otherwise lacked the will to get off the couch. Years later, she was still using them occasionally; it was how she and Jillette ended up on the same show in the first place.

Jillette never adopted the idea himself, but it stuck with him as a gripping thought experiment, and two of his friends actually ended up living by the dice for a while. He doesn’t endorse this, but their stories, he admits, are fantastic. In the spirit of the novel, I tried it out myself for his talk in Portland, letting the dice decide whether I would have the night to myself or invite an online match for a first date. I weighted the odds toward the date, covering the middle of the distribution. The dice had other plans; I rolled a two and enjoyed a solo steak dinner instead.

I’ll never know if this was the optimal outcome, and it was certainly less exciting than Bobby’s adventures in Random, but I’ve kept a pair of dice rattling around in my laptop bag ever since. Jillette would advise leaving the meaningful use of them to fiction, but it’s a testament to his storytelling that the temptation to shake things up by rolling on more decisions persists. What could go wrong?

Jacob Grier is the author of several books, including The Rediscovery of Tobacco, Cocktails on Tap, and Raising the Bar.