Genius musicians and their scolding critics

Eric Felten

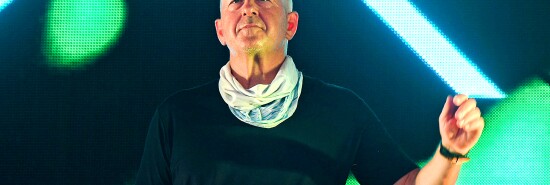

Leave it to the New York Times to ruin a good time. With all the troubles in the world, the paper finds a way to take something unobjectionable — Goldman Sachs CEO David Solomon’s side hustle as a DJ mixing and remixing beats — and turn it into a tut-tuttable moment. The New York Times feigns concern that Goldman is headed for wrack and ruin just because the company’s CEO takes some time out of his schedule for the musiclike enterprise that is DJ-ing.

Not getting very far with that assertion, the writers of the story switch instead to the argument that Solomon is abusing his corporate power, that he uses his status and wealth to hoover up gigs that, were the music business operated on principles of unsullied merit, should really have gone to someone else. Clutching its pearls, the New York Times raises “questions about whether his opportunities” as a mix master “have come about because of his talent or his position as the leader of Wall Street’s most elite investment bank.” The New York Times lacks evidence of any particular malfeasance, and so the paper turns to insinuendo. For example: “Mr. Solomon’s hobby occasionally brushes up against his day job in ways that could pose potential conflicts of interest.” My, but that’s an awful lot of maybe packed into a single sentence. Solomon’s DJ gig “occasionally brushes up against his day job in ways that could pose potential conflicts of interest.” Hard-hitting stuff.

All of which raises questions about whether it is possible the paper of record is having us on. Does Solomon’s wealth and power present to him opportunities that others don’t get? I know it’s hard to believe. The next thing you know, they’ll expect us to believe that Sofia Coppola starred in The Godfather Part III because she auditioned best.

There’s nothing odd about people with serious, time-consuming jobs succeeding at serious, time-consuming pastimes. Physics brainiac and Nobel laureate Werner Heisenberg was musical: He managed to find time to sneak in some piano while inventing quantum mechanics. Doobie Brothers guitarist “Skunk” Baxter was a credible game theorist. Physicists and violinists Albert Einstein and Max Planck were said to play duets together.

What does it take to be successful at the highest level? “You have to be determined and work hard,” according to David Julius, who recently won a Nobel Prize for his work in medicine. “But I think emotionally you have to be relaxed and enjoy the process.” Being a scientist is “not so different than being an artist. You’re responsible for your own creativity. You have the freedom to fail to succeed.”

Over the last decade, psychology professor Kevin Eschleman has been researching how extracurricular activities affect people who have boatloads of serious work to get done. Interviewed by NPR in 2014, Eschleman said, “We found that in general, the more you engage in creative activities, the better you’ll do.”

“Organizations may benefit from encouraging employees to consider creative activities in their efforts to recover from work,” Eschleman has argued. “It becomes incredibly more valuable if it is different from what you’ve been doing most recently in your work environment.” For an investment banker, donning the old headphones would seem to count admirably.

If you want to see what concomitant careers in business and music really look like, consider composer and insurance executive Charles Ives. His business career began at Mutual Life, but he soon founded his own firm, Ives & Co., and became a pioneer in estate planning, writing, among other guides, a 1918 booklet titled Life Insurance with Relation to Inheritance Tax. Hardly the stuff one would expect from the preeminent American composer of avant-garde modernism.

If Ives hadn’t been a well-to-do businessman, there might never have been a performance of his mind-bending orchestral work Three Places in New England. The second movement was written to sound like two marching bands coming from different directions and playing at different tempos. As they seem to pass one another, dissonances come and go. It is an astonishing act of polyphonic creativity. And it might never have been heard if Ives were a typical starving artist. Not only did Ives put up the money to have Three Places performed, he paid to have it published, too.

Maybe more musicians should be corporate executives.

Eric Felten is the James Beard Award-winning author of How’s Your Drink?