The preposterous Norman Mailer

Peter Tonguette

The woke among us may have lived with a book, movie, or public figure all of their lives, but at some point, they allow themselves to be jarred by what they had previously taken for granted: Nabokov’s Lolita is about what? John Wayne said what? George Carlin told a joke about what? The inherent unfairness of this exercise is not considered. All that matters to the woke is that they are more righteous than those who lived, worked, and made art Before.

We’re all a little tired of hearing about their findings. Today another painter is ruled problematic by a New Yorker essay for indulging the “male gaze,” the Manhattan magazine’s newest hire from Kenyon having apparently just heard about Paul Gauguin. Tomorrow it will be a ponderous opinion essay in the Washington Post about what race of millionaire sex bombshell actress may pretend to be a cartoon robot in a movie or a take in the Atlantic about how Lady Gaga is a cultural appropriator. (Each of these examples is real.)

So long as the entire exercise of criticism is not exhausted by moralizing at the past, however, it can make sense to be at least a little horrified by what someone once did, said, or thought. Before there was cancel culture, there was the good old-fashioned critical reassessment — a perfectly legitimate enterprise.

Few literary figures of the last century are more deserving of such scrutiny than novelist Norman Mailer (1923-2007), whose lifetime of outre behavior, outrageous statements, and questionable judgment, personally and professionally, deserve an honest reckoning. In fact, one reason to think of Mailer for reexamination is that he was not merely a thoughtcriminal or breaker of artistic norms; he was a violent criminal and a friend of violence. He stabbed the second of his six wives, Adele. He headbutted Gore Vidal behind the scenes of The Dick Cavett Show. And he aided in the release from prison of a murderer whom he judged to be a literary talent, Jack Henry Abbott.

Nonetheless, or possibly because of what a rule-breaker he was, he seems a very likely candidate for rehabilitation by the otherwise admirable anti-woke resistance, whose first instinct is to rush to the defense of any rascal it encounters. To that resistance, I say: Watch out. Yes, Mailer was a formidable if inconsistent writer. The Executioner’s Song is a masterpiece. And his excesses can easily be excused as examples of the sort of masculine pugnaciousness currently under attack by the Left. It will be especially tempting to take up Mailer’s cause since his works are sure to be increasingly sidelined from the mainstream. Just last year, his longtime publisher, Random House, declined to put out a gathering of his essays. (Skyhorse, the independent publisher of choice for the canceled, inherited the volume in question, A Mysterious Country, which is out this month.)

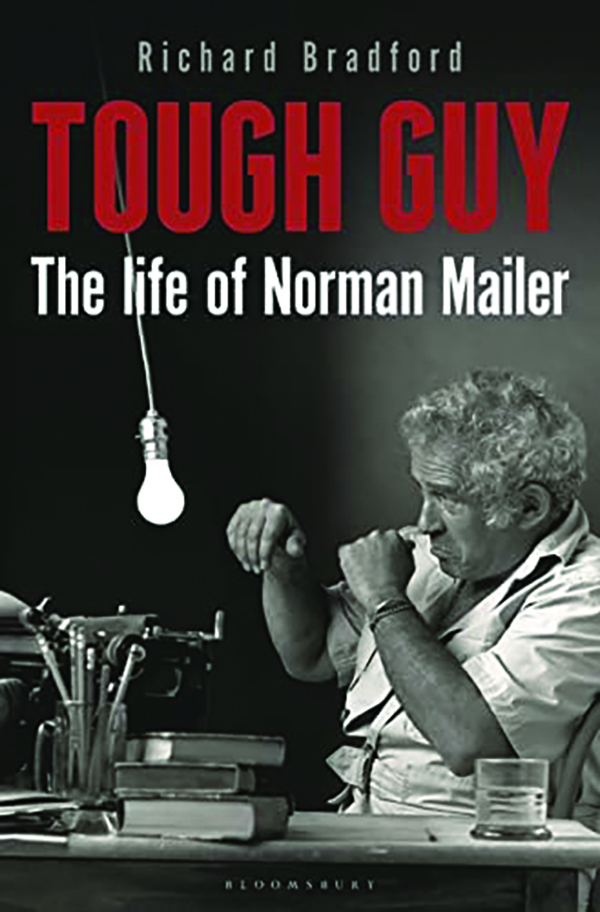

A good illustration of the risks of elevating Mailer to sainthood is found in a new biography. Richard Bradford’s Tough Guy: The Life of Norman Mailer is a slender volume that tends to summarize huge amounts of information in single pages and, as such, compares unfavorably with the sweep and scope of J. Michael Lennon’s definitive biography of Mailer. On the other hand, Bradford’s hasty approach — his eagerness to make quick judgments and get on with the story — has the advantage of plainly and clearly stating Mailer’s profound limitations.

Early in the book, Bradford makes typically quick work of an altogether astonishing encounter between a young Mailer, then cocksure with the success of his brilliant World War II novel The Naked and the Dead (1948), and Dorothy Parker. “Parker and her tiny poodle were introduced to Bea, Mailer’s pregnant first wife, and Karl, his gigantic, restive German Shepherd,” Bradford writes. “Mailer did his best to restrain Karl, who after taking a sniff at Parker’s dog made a frenzied decision to eat it.” Concludes Bradford, “As reports of Mailer’s ostentatiously bad behaviour became commonplace, the boundary between Karl and Mailer began to fade.”

Indeed, Bradford offers plenty of evidence that Mailer, by all rights, belonged in the doghouse for much of his life. At times, the book resembles a kind of inventory of Mailer’s infidelities, bad habits, and highly debatable pronunciamentos. We learn that Mailer and his second wife, Adele, the one whom he would stab in 1961, traveled to Mexico in search not only of their beloved marijuana but mescaline, with which they experimented liberally and always rather pretentiously: The couple, Bradford writes, “treated the terrifying effects of the drug as a process of countercultural initiation.”

Indeed, Mailer’s desire to unshackle himself from the bonds of normal society — his famous abhorrence for plastics, contraceptives, television, and other modern innovations is detailed here — seems to have been the wellspring for his most odious conduct. Prior to the stabbing incident, Bradford writes, “Mailer appeared to be experimenting with various forms of physical antagonism,” including “staring matches” with women. At least at the time, Mailer even perceived the stabbing itself in perverse, self-serving terms. “Do you know that I watched you being wheeled into the operating room, and I’d never seen you look so beautiful,” Mailer is said to have told his wife at the hospital. “Do you understand why I did it? I love you and I had to save you from cancer.” It goes without saying that the “cancer” to which Mailer refers is — ahem — psychic, not physical.

Bradford makes clear that this episode, which resulted in Mailer being dispatched for a time to the Bellevue Hospital and hastened the inevitable demise of his marriage to Adele, did not satiate the author’s appetite for combat. In his notorious 1970 film Maidstone, Mailer and actor Rip Torn are seen in a famous on-camera scuffle that included the author being whopped on the head and the actor being bitten on the ear. There’s little doubt that the conditions for such a melee had been set by Mailer. (“Had Torn been charged with assault,” Bradford dryly notes, “he would probably have been the first person to be found not guilty by reason of postmodernism.”)

And, years before he headbutted Vidal on Cavett’s talk show, we read of Mailer turning up at Truman Capote’s Black and White Ball in a “dirty gabardine raincoat and a shabby, unwashed suit” and proceeding to invite a number of male guests to “step outside.” There is even a kind of companion episode to the Vidal incident: While waiting with Mailer to appear on another talk show — this time, Merv Griffin’s — Pete Hamill recalls dodging multiple punches thrown by the literary giant. “Not hitting you, Pete, takes something out of my character,” Mailer offered by way of explanation.

To say Mailer shouldn’t be canceled is a step short of saying he ought to be lionized or emulated or viewed as a kind of guru for today’s young and disaffected. (One worries about followers of, say, Jordan Peterson who might stumble upon Mailer’s warnings about the “womanization” of America.) As late as 1995, when he wrote a mostly forgettable book on Lee Harvey Oswald, Mailer remained all too besotted with the figure of the violent renegade, the scoundrel, the nonconformist — the exact sort of civilization-destroying rogue he so often saw himself as and wished himself to be. “Oswald, then, is Mailer’s quintessential visionary malcontent, the hipster of ‘The White Negro’ and Rojack of An American Dream,” Bradford writes, connecting the dots.

In hindsight, that Mailer continued to secure huge publishing deals — one of the most amusing of which was $1 million secured for a novel that was grandly but vaguely promoted as concerning “the whole human experience” — and remained attractive to women is a cause for astonishment. When courting his last and most devoted wife, Norris, Mailer sent her “a crate containing every one of Mailer’s hardback publications, signed by him.” Well, that’s one way to win a woman’s heart. Bradford may not be a first-rate stylist or a biographer of great depth, but he has a gift for making Mailer look and sound preposterous — and rightly so.

Peter Tonguette is a contributing writer to the Washington Examiner magazine.