Dahl that glitters

Peter Tonguette

When I was growing up, I worked my way eagerly through the works of Maurice Sendak, and then E.B. White, and then Beverly Cleary. By the time I finally reached the novels of Roald Dahl, however, I knew I had found my happy — that is to say, naughty, rascally, puckish — place.

Dahl, the son of Norwegian parents who was born in Wales in 1916 and died in 1990, wrote what seemed to my 7-year-old self an endless series of fantastical, engaging books that were at once delicious and malicious. Charlie and the Chocolate Factory did not merely allow the child reader to enter a dream world of boundless chocolate but also indulged other, more malevolent fantasies, such as when the hoggish Augustus Gloop is deposited in a vat of liquid cocoa.

James and the Giant Peach, The BFG, and Matilda each had the same spirit of unrepentant devilishness, though my favorite of all was The Witches. My appreciation of this account of ghoulish harridans possessed by the idea of turning children into mice was enhanced by the extraordinary 1990 film adaptation directed by Nicolas Roeg and starring Anjelica Huston. Roeg understood that a movie about witches should make those witches as nasty as possible.

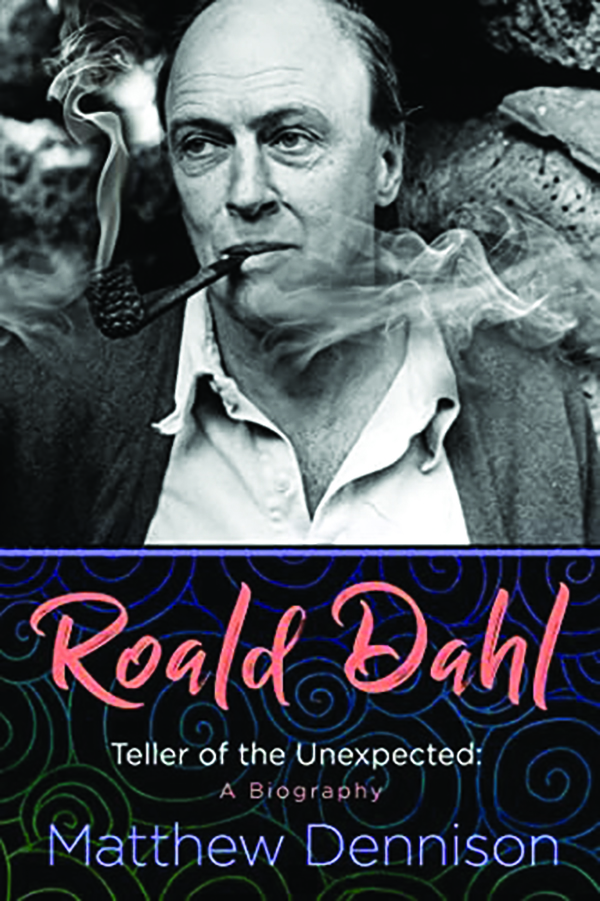

Of course, fairy tales and stories aimed at children have always trafficked in the scary, but the nature of Dahl’s unique and uniquely enrapturing fiendishness is explored in a slim but perceptive new biography of the author, Roald Dahl: Teller of the Unexpected, by Matthew Dennison. Dennison locates the source of Dahl’s narrative sensibilities in an unusually dramatic childhood: “Personal experience, beginning with the unremembered traumas of his father and sister’s deaths, would convince Roald of the ubiquity of caprice in human lives.” Equally consequential was the atmosphere of storytelling that pervaded the Dahl family. “Nursery rhymes, fairy tales and folklore provided his first introduction to unanticipated, frequently fearsome outcomes, tropes that played their part in shaping his fictional vision,” Dennison writes.

Dahl’s miserable stints at English boarding schools instilled anti-authoritarianism, an essential trait for a children’s book author. “We were caned for doing everything that it was natural for small boys to do,” he wrote in 1977, though Dennison credits his schooling with imparting some important literary principles, including the advice of his English master, John Crommelin-Brown, who advised: “Always use the short word instead of the long one.” Dennison continues: “[Dahl] remembered his English teaching as focused on building sentences that captured precisely what the writer intended, one aspect of his own succinct and pithy manner afterwards.”

Succinct and pithy, yes, but let us never overlook Dahl’s florid imagination, equally as capable of summoning a child’s nightmares as his dreams. As Dahl said of children and the worlds they like to escape to, “They love being spooked. They love suspense. They love action. They love ghosts. They love the finding of treasure. They love chocolates and toys and money. They love magic.”

Surprising for a writer so attuned to the preferences and predilections of young people, Dahl took a long and winding road to settling on actually writing children’s fiction. The Gremlins, a 1943 storybook about the insubordinate little creatures who stir up trouble in the RAF, sprang from an unlikely abortive film project with Walt Disney. Yet Dahl remained focused on short fiction aimed at grown-ups for close to 20 years after that until the intervention of his agent, Sheila St. Lawrence. The seed planted, Dahl let his imagination run wild. “Roald had found himself looking at a cherry tree,” Dennison writes. “What would happen, he wondered, if the cherries were to grow and grow and not stop growing? He asked the same question about apples and pears. And then he thought of a peach.”

James and the Giant Peach, when published in 1961, was a fulsome triumph, though it coincided with a period nearly as tumultuous as any during Dahl’s youth. Among the children born from his marriage to actress Patricia Neal, one child (Theo) suffered a potentially catastrophic injury, and another (Olivia) died after falling ill with measles. Neal herself was felled by cerebral aneurysms. In each case, though, Dahl drew on his inner reserves of resourcefulness. He helped develop medical technology that saved Theo, sought to understand the circumstances of Olivia’s illness and death, and practically browbeat Neal to recover her faculties and her strength. “The key thing was not to get depressed and feel sorry for yourself,” Dahl said. “Do something. Anything was better than nothing.” Dennison concludes that Dahl became persuaded of his “ability to shape events by force of will.”

Dennison paints a portrait of a man who lived and wrote in bold strokes. “Competitive, including with himself, he needed his writing to be successful, and calibrated his success in dollars,” writes Dennison, who gives a full account of one of Dahl’s most nakedly commercial endeavors: as a screenwriter in the 1960s of a James Bond movie and Chitty Chitty Bang Bang. Dennison is right to regard Dahl’s 1975 novel Danny, the Champion of the World as self-aggrandizing: “Danny’s love for his Roald-like father is straightforward and wholehearted, and his admiration embraces the man as well as the parent.” We believe Dennison when he writes that Dahl aimed to answer each piece of correspondence from his youthful fans.

Yet Dahl’s immoderate nature permitted him to make horrible mistakes, too. Despite the gallant support he gave to an ailing Neal, Dahl left his first wife for a younger woman, Felicity Crosland, whom he married in 1983. That same year, Dahl made a series of vile, crude antisemitic remarks that tarnished his reputation, and rightly so. To his credit, Dennison doesn’t flinch from, or attempt to explain away, this mighty flaw in Dahl’s makeup.

Notwithstanding his personal limitations and errors in judgment, Dahl, whose service in the RAF and career in British intelligence is also covered at length, remains one of those rare writers whom a child can follow into maturity: His short story collections, including Kiss Kiss and Switch Bitch, are some of the best of the last century. Yet, no less than those grown-up works, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory and The Witches and so many others still bewitch the misanthropic child each of us once was.

Peter Tonguette is a contributing writer to the Washington Examiner magazine.