The media find themselves once again under public scrutiny following dubious reports from legacy outlets about federal activity in Minnesota, devastating layoffs, and the news of a former CNN darling indicted by a federal grand jury.

Those events come amid a troubling backdrop. Trust in the press hit a record low in October 2025 at 28%. Americans, particularly those on the Right, view the media as a punching bag — rabidly biased, hunting not the truth but Republicans, out of touch with America and Americans, and bent on inflaming existing ruptures in the nation’s social fabric.

For those perhaps Pollyannaish enough to hope that an institution important enough to be protected by the first constitutional amendment offered by our nation’s founders could be more than a punchline, the situation seems bleak. But despite how it feels in the ever-online, nonstop world of American politics, we shouldn’t write off the possibility of return just yet. The press have come back from extinction before.

The Republican president, and many of his supporters, call the legacy media “the enemy of the people.” The list of real grievances is long. The media led a yearslong crusade attempting to prove that President Donald Trump was a Russian asset and have invented conspiracy theories about and tied to him and Republicans at every turn. It isn’t lost on the public that these same journalistic voices collectively covered up the cognitive decline of former President Joe Biden. The errors and omissions cut seemingly uniformly in the direction of the Democratic Party.

Beyond their own failures, systemic forces weigh on the self-described “defenders of democracy.” Advertising revenues, long the backbone of media financing, are in freefall. Once-august newspapers are being bought up by private equity firms and sold for parts.

And there are new challengers — Substack, where outlets can be built in a year that rival esteemed newspapers; podcasts that reach and influence millions; X, formerly Twitter, whose owner declared that its users were “the media now”; YouTubers who can bring federal action with a single video. These entities and individuals don’t play by the legacy media’s rules — able to churn out content more quickly, with fewer content guardrails, for good and for ill.

It’s easy to wax poetic about all the ideal improvements that could be made to fix the media. A Scott Jennings in every panel discussion. A conservative in every newsroom. But recent efforts at increasing viewpoint diversity in the press have been miserable failures. New CBS News Editor-in-Chief Bari Weiss rose to a household name only after she was run out of the New York Times by a staff that called her a Nazi for what the paper would later call her well-known habit of questioning “aspects of social justice movements.” The COVID-19 pandemic and a national convulsion on issues of race in the years that followed caused the press to drift further from the reality that many people saw around them.

But those declaring the end of the legacy media may be getting ahead of themselves.

Discussion about declining trust in the media usually starts from about 1970, and the polling indicates a precipitous drop since the days of three primary news channels and uniform coverage that marked that era. It can be easy to imagine an idyllic mainstream press of yore, undercut by bias in recent decades.

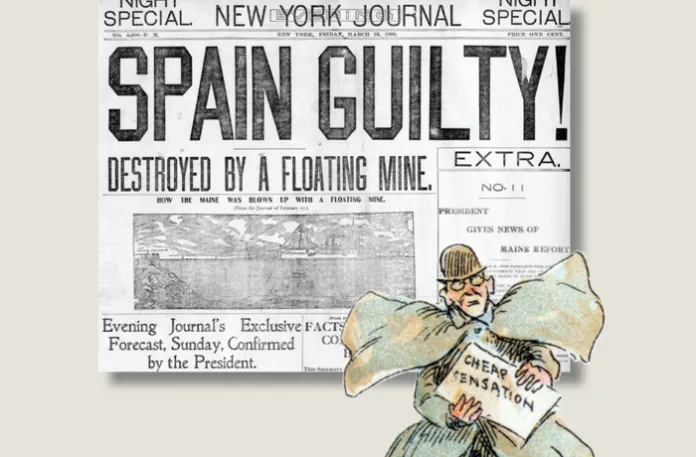

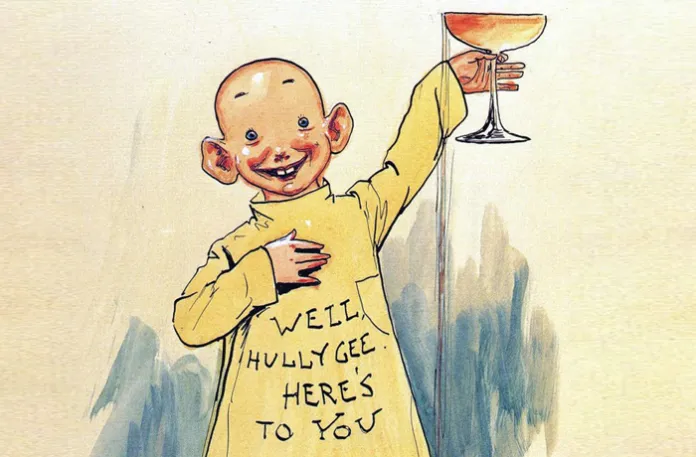

But that ignores the evolution of the institution, once marked by openly partisan hatchetmen using newspapers as personal and political weapons and sensationalists selling snake oil. This so-called “yellow journalism” came to dominate the industry, with shoddy reporting, partisan fiction, and utter drivel overtaking the media industry up until the turn of the 20th century.

From there, the media were captured by the Office of War Information, tasked with producing and placing material in support of the war effort, with the media acting as willful stooges. That was obviously a noble cause, but a free and fair press holding power to account simply didn’t exist. Thereafter, much of the media was co-opted by the FBI under J. Edgar Hoover. It wasn’t until the 1970s that a bludgeoned, embryonic version of what we think of as the “mainstream media” crawled into existence, newly invigorated by President Richard Nixon’s Watergate scandal.

The early days weren’t perfect. Monolithic coverage buried inconvenient truths. Political parties took advantage of stodgy rules of decorum and expected standards. But the institution of the media largely reflected the public at the time, as former NPR editor Uri Berliner has described. But the media’s rails really started to come off when so many other rails did: around 2016, when The Apprentice host Donald Trump became President Donald Trump.

###

After years of intractable resistance to the idea that the media’s way of conducting themselves was a death wish, at least some outlets appear willing to fight to survive. The latest case is CBS News’s decision to hire Weiss, founder of the Free Press, a Substack publication with 1.5 million subscribers.

Weiss’s ascension has been met with uniform opposition from her compatriots in the legacy press. But far from turning the outlet into a MAGA front, she’s invested in doing the type of reporting people are actually interested in rather than a 24/7 focus on Trump’s latest outrage. And she’s doubled down on doing more rigorous journalism, absent the advocacy that has come to dominate so many outlets, recognizing that the old business model won’t survive.

There have been bumps, as is to be expected with a new executive. And conservatives may well take issue with some of Weiss’s politics and managerial style. But the recognition from CBS that it desperately needed something new, and went out and found a compelling voice to do so, is encouraging.

The goal isn’t, and shouldn’t be, to create a clone of Fox News, but an outlet that competes with old guard news stations for viewer interest — something Weiss has done at the Free Press.

Other outlets are starting to wake up to these financial realities, too. In 2023, CNN undertook a now-failed effort by Chris Licht to make the outlet’s coverage more relatable. With ownership still unsatisfied by the station’s performance, CNN reportedly could soon come under the same ownership as Weiss’s CBS. The Washington Post just announced it was slashing hundreds of jobs in and tied to the newsroom. The new direction is concerning — why, when the outlet is failing to provide a good product to millions of possible local readers, would the outlet reduce its Metro desk, cut its vaunted sports coverage, and lean into politics? Did the management of the paper learn nothing from what the Trump-as-media-meal-ticket phenomenon has done to the press? — but any response to the current destruction-level threat is better than the press’s response to date.

And this type of creative destruction, especially with new media outlets such as the Baltimore Banner waiting in the wings, might be precisely what the institution of the press need right now, in a fractal media environment where audiences no longer crave the newspapers of yesteryear.

This cycle of self-inflicted destruction and painful rebirth is precisely what ended the last era of dishonest reporting. The old yellow journalism of the late 19th century didn’t give way because newsrooms were moved by their better angels or journalistic integrity. It ended in large part because the race to the bottom eroded the bottom line for wealthy outlet owners such as William Randolph Hearst. None other than the New York Times stepped into the void created by yellow journalism to offer fact-based, so-called “grey” journalism — “all the news that’s fit to print,” as the saying goes. Readers bought in. The New York Times’s circulation exploded. Other outlets soon followed suit. That provided more interest and revenue to launch the age of “muckrakers,” journalists who blew the whistle on government fraud and dangerous and unethical business dealings — akin to how the best journalists often operate today. And these two areas of focus dominate the headlines today, too.

There’s only so much that can be done to attempt this sort of shift from without. Solutions to the deeply entrenched legacy media of today should therefore be rooted in the press’s perception of self-interest.

More legacy outlets, if for nothing other than their own survival, need to follow CBS in recognizing that they don’t know everything and are, in fact, deeply and dangerously blinkered by newsrooms staffed almost uniformly by people who see the world the same way.

And news outlets, or perhaps their owners, should also recognize that, done well, there is money to be made in journalism. Tens of millions of people still reliably read newspapers and magazines — 22% of Americans pay for some form of media consumption, a number that has doubled since 2014, even as trust has cratered. It isn’t a loss of appetite for news driving readers away.

Recognizing how much would-be consumers resent the product will be necessary to combat the media’s most existential threat: the largest voices in the newsrooms and leadership of the legacy press, who have been resistant to change for years. The “cathedral” of top journalists with expensive pedigrees, deep-blue biases, and sensibilities out of touch with everyday people is the rot at the core of the legacy media.

Members of the media are substantially more liberal than the general public, a phenomenon considerably more obvious in the upper echelons of papers and outlets.

Outlets are riddled with petty backbiting, off-the-record sniping at coworkers, and an unwillingness to admit that declining trust isn’t someone else’s fault.

Too often, reporters moonlight as activists for the issues they purport to cover — a reality cast into stark relief by former CNN host Don Lemon’s indictment for his “coverage of a protest” where a grand jury found he actually denied worshippers their freedom of expression. In near unison, the legacy media have reported the fiction.

This helps explain why newsrooms such as the New York Times have been engulfed by struggle sessions over outlets’ decisions to publish widely supported conservative arguments, or permit conservative voices a seat at the table, or allow anyone to so much as question liberal sacred cows. For the press to regain an iota of trust among the public, people must have confidence that these operations aren’t entitled daycares. Strong leadership willing to throw away the pacifiers would help.

And real accountability could help make an institution famous for refusing to concede its errors more responsive when the facts land in the opposite direction.

Conservatives are right to be skeptical that the media will change. But this is precisely how the old era of yellow journalism ended: outlets focused on becoming more credible because they couldn’t sell their product; because readers would no longer pay for political hatchetry and sensationalist nonsense, seeking instead real news, from all perspectives, on the topics that matter. As New York Times publisher Adolph S. Ochs declared in 1896:

Give the news, all the news, in concise and attractive form, in language that is parliamentary in good society, and give it as early, if not earlier, than it can be learned through any other reliable medium; to give the news impartially, without fear or favor, regardless of party, sect, or interests involved; to make the columns of THE NEW-YORK TIMES a forum for the consideration of all questions of public importance, and to that end to invite intelligent discussion from all shades of opinion.

Those of us on the Right sometimes forget that the media are, for all their sins, a consumer good, governed by a market that responds to its participants. And as the success of Substack makes clear, people are still willing to pay for something a cut above internet slop.

A CONSERVATIVE CASE FOR A WAR TAX

And to those who might cheer the death of the legacy press, it’s valuable to remember why we care about what the media do so much. Any country, but particularly the United States, needs a well-operating free and fair press — to report on what’s happening around the world, to hold power to account, to investigate malfeasance effectively, including the tens of billions of dollars in welfare fraud across the country. While the absence of local media hurts a community, part of what’s needed is to wait and allow natural selection to play out, as it did at the end of yellow journalism.

There’s a reason the First Amendment protects journalism. There’s a reason the institution’s recent decline in quality incenses so many. But this might only be the end of one unseemly epoch, not the end of the institution.

Drew Holden is the managing editor of Commonplace and author of the Holden Court Substack.