As the snow settles on the great Greenland war that never was, the cracks in the Atlantic alliance widen like melting ice packs in the Arctic spring. The “rules-based international order,” that white whale of the golden age of globalization, is declared dead — if it ever existed in the first place. We hear that President Donald Trump has opened a new and dismal age of brute force, though political orders are always underpinned by threats of violence. We also hear, especially from Trump, that the Western alliance is reviving and that the slackers of European NATO are following American orders to rearm — while European leaders and the Canadian prime minister tell their nations that they must now form a “middle-tier” between Washington and Beijing.

The architecture of alliance structures remains in place. But the façade that has crumbled for three decades has finally cracked. In the decades after 1917, the United States became the world’s preeminent anti-imperial and liberal power. In the years since 2016, it has become an exponent of Machtpolitik, power politics. The liberal system that the U.S. built after 1945 is buckling, the institutions that masked the underlying architecture of force crumbling. The emerging future is the forbidden past: the real-time return of the old great-power politics of empires, spheres of influence, and “offshore balancing,” the use of allies, clients, and “middle-tier” alignments as levers against enemies and rivals.

In the 21st century, America will either be relegated to the horizon of a Chinese-dominated Eurasia or become history’s biggest offshore balancer, exploiting its alliances and advantages to secure the ability to act independently and project itself globally. Either way, America will become an empire in all but name, competing with the historic empires of Russia and China, and possibly also Turkey. India and Israel are emerging as pivot states, and Iran will too. Meanwhile, the pillars of America’s Atlantic security system are wavering as Europe falters and Canada breaks away. The urgency of the moment explains why, when Trump went to the World Economic Forum at Davos, Switzerland, on Jan. 21, he dropped the f-bomb that has been banned in Europe since 1945.

A great piece of ice

“I won’t use force,” he told the WEF. “I don’t have to use force.” The U.S., Trump said, needs the “right, title, and ownership” of Greenland in order to keep its “very energetic and dangerous potential enemies at bay.” Never one to avoid mentioning brute facts brutally, Trump reminded the world that no one else is in a position to resist American interests in the Arctic and no one else is willing to underwrite Europe’s security.

Russian and Chinese companies are circling Greenland’s reserves of critical minerals and rare earth elements. The melting Arctic ice is opening a seasonal route between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Greenland, a semi-autonomous Danish territory, cannot defend itself, and Denmark cannot defend it. The only Western power capable of securing Greenland is the U.S. American missiles and early-warning systems have been stationed on Greenland since 1953 because that “big, beautiful piece of ice” guards the polar approaches to the U.S. The U.S., Trump said, will augment North America’s protection with a Golden Dome — like Israel’s Iron Dome missile defense system, only in gold.

A few hours later, Trump met privately with Mark Rutte, the Dutch secretary-general of NATO. Afterwards, Rutte announced that they had reached the “framework of a future deal” on Greenland. Trump withdrew the tariffs that would have come into effect on Feb. 1 to punish the eight European states that had sent symbolic military observers to Greenland. Greenland, European officials suggested, would cede mining rights to American corporations and territory to new American military bases on terms similar to the 1960 treaty by which Britain permanently secured sovereignty over Akrotiri and Dhekelia on the Mediterranean island of Cyprus.

In 2018, then-Danish Prime Minister Lars Løkke Rasmussen told the Danish Parliament that Greenland “must make it clear to itself and the Danish government” on whether it wanted to remain part of the Danish commonwealth or declare independence. Now, however, Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen asserted that “we cannot negotiate on our sovereignty.” Greenlandic Prime Minister Jens-Frederik Nielsen said he did not know what was in the deal but used Frederiksen’s language of “territorial integrity,” “international law,” and “sovereignty,” and echoed her call for NATO to be involved.

A NATO spokesman denied that Rutte had offered “any compromise to sovereignty.” But Frederiksen’s call for a “permanent presence for NATO” on Greenland could be describing Britain’s air base at Akrotiri on Cyprus. Meanwhile, Trump talked up a deal with “no time limit” that grants the U.S. “everything we want at low cost.” It looked like the Danes and Greenlanders had been bullied into surrender, with the terms to follow. The lawyers will negotiate the rest — and negotiations, as Trump likes to say, are there to be renegotiated.

Mid-tier crisis

After a decade of Trump, America’s NATO allies know his game. He says something outrageous to tip the table over, then resets it on his terms. The outcome adjusts an existing balance in the U.S’s strategic favor, but the tactic erodes trust. The Greenland episode was typical. The volume of Trump’s bark seems to have counted for more than the modest bite he had in mind. The same went for his disgracefully false claims about NATO allies’ commitment in America’s imperial follies in Afghanistan and Iraq — claims that elicited a rare Trump reversal by social media post.

America’s NATO allies also see opportunities when Trump induces a crisis. When he sets American patronage in play, he floats the value of the patronized. When he shows that treaties are the fictions that mask the reality of power, he suggests that the less powerful can renegotiate, too. The performative disgust of America’s allies resembles that of Captain Renault in Casablanca. “I’m shocked, shocked to find that gambling is going on here,” Renault says, as the croupier hands him his winnings.

America’s allies are playing the margins. France usually plays the best hand in this game. At Davos, French President Emmanuel Macron advocated “rebalancing” with China. With the U.S. and the European Union at odds on tech regulation, Macron called for Sino-European tech convergence. “China is welcome, but what we need is more Chinese foreign direct investments in Europe in some key sectors, to contribute to our growth, to contribute to our technologies and not just to export,” Macron said, wearing aviator-style mirror shades to cover a burst blood vessel in an eye. They were not Ray-Ban aviators but a 20th-century American technology transfer, knocked off by Maison Henry Jullien.

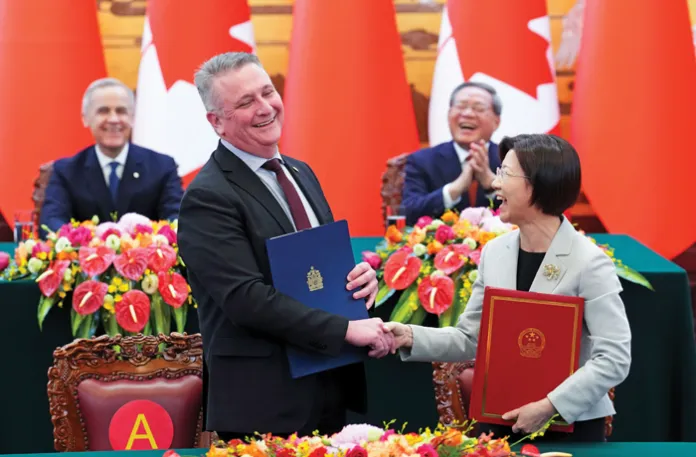

Before going to Davos, Canada’s unelected prime minister, Mark Carney, went to Beijing for the first visit by a Canadian premier since 2017. There, Carney secured what he called a “preliminary but landmark” trade deal. Chinese President Xi Jinping praised Canada’s “turnaround.” Carney explained that he needed to position Canada for “the world as it is, not as we wish it” in what he called, in a dizzying inversion of President George H.W. Bush’s line, a “new world order.” In Beijing, Carney proposed “two-way energy cooperation” with China, which is already second to the U.S. among Canada’s trade partners, and to “accelerate Chinese investment” in Canada.

“Today, I will talk about a rupture in the world order,” Carney told the WEF at Davos, “the end of a pleasant fiction and the beginning of a harsh reality.” American allies always knew that “the story of the international rules-based order was partially false,” but the going was good under “American hegemony.” But the multilateral “architecture” has been undermined by great powers using “economic integration as weapons, tariffs as leverage, financial infrastructure and coercion, supply chains as vulnerabilities to be exploited.”

Carney pursued the theme of a world turned upside down into moral inversion. He cited Czech dissident Vaclav Havel’s 1978 essay “The Power of the Powerless.” A shopkeeper puts a card reading, “Workers of the world unite,” in his window to “signal compliance.” Havel called this “living a lie.” The implication is that the American-led economic and security system is a tyranny like the Soviet Union was.

For “middle powers” such as Canada, Carney said, the frameworks of integration have become “the source of your subordination.” Canada’s answer, Carney said, was “diversifying abroad” through trade deals with China and Qatar while exploiting the American-run sources of subordination to project interests in Greenland and Ukraine. The middle powers must “create a third pact”: more “rebalancing” toward China and away from America.

On Jan. 28, Keir Starmer and 60 British business leaders landed in Beijing. It was the first visit by a British prime minister in eight years, since Theresa May took a 50-strong delegation to Wuhan in 2018. “On this delegation, you’re making history,” Starmer told the businessmen. “You’re part of the change that we’re bringing about.”

European vacation

Carney’s proposal that mid-tier powers combine into an independent bloc to exploit tensions between America and China is an unrealistic response to an obvious reality. It is unrealistic because the mid-tier powers share little in common beyond a predicament and a desire to cash in on Chinese trade while they can. It is unrealistic because a Canada that orients its energy exports toward China is a threat to what the National Security Strategy of December 2025 called the “hemispheric” dominance that is the foundation of American security. Yet Carney’s cant is realistic in identifying the crack-up of one era and the return of the old geopolitics.

That geopolitics has forced the U.S. to reconstruct the domestic foundations of hard power. The explicit doctrine of hemispheric dominance is the culmination of post-2016 policies that went from Trumpian heresy to Biden-era orthodoxy, such as onshoring key supply chains, reviving the industrial base, and expanding domestic mining. The demand that NATO “free riders” pay their way to allow the U.S. to “pivot” to pressing challenges in Asia goes back to Barack Obama’s presidency and has been repeated with bipartisan regularity.

The Europeans refused to accept the news that their American-funded vacation from history was over until Russia’s second invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. The Biden administration refused European requests to put American soldiers on the ground or deploy American jets to create a “no-fly” zone. Instead, it played the offshore balancer. It sent weapons and money to ensure that Ukraine did not lose and Russia did not win. This balance of destruction did not collapse Russia’s economy and regime as expected. It led to the formalization of a Sino-Russian alliance.

The Europeans struggled to form the “mid-tier” alliance that Carney now recommends. Britain resumed its historic strategy of being Europe’s offshore balancer, seeking to prevent the emergence of a dominant power on the continent, and backed Ukraine heavily. But Germany’s economy was hamstrung by the cessation of Russian gas supplies, so Germany did as little as possible. France flipflopped, with Macron launching solo peace initiatives and then calling for European troops on the ground. The only consistent response came from the bloc of EU states between the Baltic and Black seas. These were the successor states to the old Central Europe for whom history had never gone away.

The European vacation from history is over, but a security vacuum persists. Still, like the French-led response when Turkey menaced Greece in January 2020, the varying European responses to the invasion of Ukraine showed how, as America offshores its European interests, the old patterns of microalliance and temporary alignment are returning to Europe. The strategic risks to the U.S. of NATO allies dividing in their efforts to rule are clear and present.

Look east

A strong Europe under American patronage serves America’s interests. A strong Europe capable of acting independently will, sooner or later, challenge American interests and maximize its leverage by “rebalancing” between the U.S. and China. The same goes for Canada, which, despite all geographical evidence, appears to think it is in western Europe, and for the Latin American oligarchies that have cultivated economic ties with China as a counterweight to American hegemony.

Europe is not going to become strong any time soon. If anything, it may slide into catastrophic weakness. The societies of Europe’s two nuclear powers, Britain and France, and its largest economy, Germany, are riven by the effects of mass immigration from the failed states of the Muslim world and Africa. The EU has regulated its members’ economies into a flatlined coma. The Eurozone’s share of the global economy shrank from 22% in 2004 to 14.8% in 2025. We are less likely to see Europe surging back to global eminence as a pivot power than we are to see it collapsing and taking down America’s Atlantic security system as it goes.

Can American security interests still be sustained through traditional channels? NATO remains the only effective means for parrying Russia, but NATO is also a Trojan horse for the neoimperial expansionism of Islamist Turkey. One reason that Europe is vulnerable to Turkish pressure is that the EU’s political development has ended far short of its targets of economic and strategic autonomy. That failure to build a postmodern empire of ideals and regulations encouraged Washington to manage the Ukraine crisis through peer-to-peer contacts between capitals, rather than via the EU government in Brussels. This dynamic feeds the emergence of mid-tier coalitions that, in an increasingly competitive global system, will be impelled to leverage their position against their American patron, as Carney, Macron, and Starmer are now trying to do.

The core of the European conundrum is, as the Trump administration recognizes, “civilizational.” The Europeans who are most committed to remaining European are also those who need America the most. It is in the American interest to bolster the central European states of “NATO east.” Britain will sign up to this, especially once its Labour government is gone. But France and the EU apparatus in Brussels will oppose any initiative that reduces their diplomatic monopolies. Germany will be aware that if old realities are back, then its interest lies in allying with Russia.

WAR FOR THE TOP OF THE WORLD: ALLIES PANIC AS TRUMP EYES GREENLAND

Stabilizing America’s interest in Europe means strengthening Europe’s eastern front under American leadership. After World War I, Polish leader Jozef Pilsudski proposed creating an Intermarium, or “Between the Seas,” federation in Central and Eastern Europe. A smaller version was realized in 1991, when the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia formed the Visegrad Group. These states are the gateway to the Eurasian heartland, which will be a key site of the new great power competition.

As the old international system breaks down, the U.S. must reconstruct one offshore imperium from the materials of another. Middle-tier coalitions are more than a transitional element in the new power politics of competition. The emerging world order is quasi-imperial in that it is structured by resource extraction and supply lines, not the old-style possession of territory. In that order, middle-tier coalitions will function much like pivot states. The U.S. has sponsored its own middle-tier coalitions in the Middle East with the Abraham Accords and in the Indo-Pacific with the Quad — the U.S., India, Australia, and Japan — the informal Squad, with the Philippines replacing Japan, and the India-U.S.-Australia trilateral. It will need to do the same in central Europe if it is to become history’s largest offshore balancer.

Dominic Green is a Washington Examiner columnist and a fellow of the Royal Historical Society. Find him on X @drdominicgreen.