The newest Game of Thrones spinoff has nothing at all to say about the Wall, the Starks, the Martells, the Tullys, the Dothraki, the Iron Islands, or the North. The only dragon we see is a handsomely constructed puppet, made, if I had to guess, of papier mache. Are we really in Westeros, the site of HBO’s multibillion-dollar fantasy IP?

The short answer — we are — is accurate but not the whole tale. Whereas the original series took as its source material thudding tomes of faux-medieval mayhem, HBO’s A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms is based on a modest novella. Not quite a comedy but certainly no labyrinthine saga, the show is perhaps best described as a Westerosi tone poem, a work of admirable depth that rarely glances beyond the nearest rise. Is it any good? Surprisingly, yes. But don’t expect geopolitical convolutions and intrigues. If Game of Thrones and its prequel, House of the Dragon, were great dynasties crushing all before them, A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms is a mere man-at-arms on a horse.

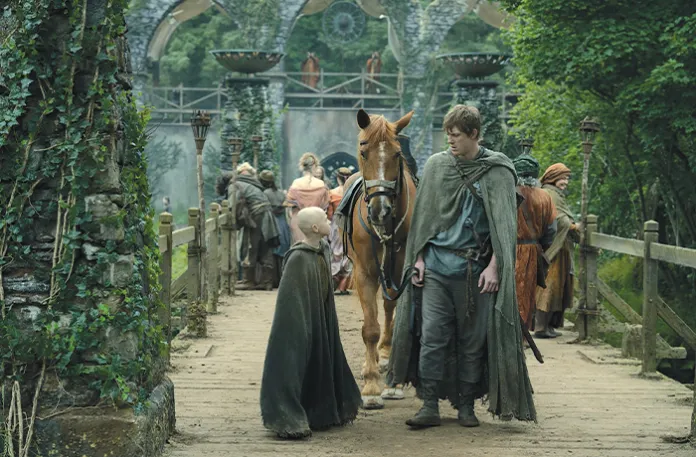

The show stars newcomer Peter Claffey as Ser Duncan the Tall (“Dunk”), a “hedge” knight, so named for his unattachment to any noble house. Recently bereft of his mentor, Ser Arlan of Pennytree (Danny Webb), Dunk is wandering the countryside when he encounters a stray 9-year-old at a roadside inn. Is Egg (Dexter Sol Ansell), as the boy asks to be called, the simple orphan and hangabout whom he claims to be, or is a more interesting game afoot? No matter. Before we can advise him against it, Dunk takes Egg into his service as squire, and the pair set off for a jousting tournament to make their fortune.

Among the production’s most obvious idiosyncrasies are its episode count and average run time. Coming in at a svelte half-dozen installments, A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms parcels out its action in 30-minute portions, a noticeable scaling back from, say, Game of Thrones’s 80-minute series finale. One reason for this leanness is that the program doesn’t even try to maintain the TV drama‘s traditional structure. Those looking for “A,” “B,” and “C” plots will search in vain. Rather, the series lingers patiently on Westerosi manners and mores: a dance-hall frolic or a stage show of balladry and fire. It isn’t until the fifth episode that we get so much as a peek at Dunk’s considerable fighting prowess, some early fisticuffs notwithstanding. Even then, the show is no more interested in the clashing of swords than it is in the children who loot the field after the battle.

Like the best high fantasy, A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms keeps one eye trained on the common folk, never letting the viewer forget that even the harshest suffering takes place, as Auden had it, “while someone else is eating or opening a window or just walking dully along.” When, midway through the pilot episode, an innkeeper mutters that she “never knew a joust to change the price of eggs,” Dunk barely looks up from his ale pot, so axiomatic is the charge. A knight of the realm, our protagonist may one day commit great deeds or protect the innocent, but he will do so in a world in which crops must be raised and taxes paid. Indeed, it isn’t until the end of the season that Dunk does anything of political consequence or note. For most of the show’s run, he is just one more bumbler, doing his level best to keep his belly full and the rain off his head.

Needless to say, Dunk’s likability is not, then, a mere function of his heroism. It is bound up instead with Claffey’s startlingly good work as a humble man thrust into increasingly dire circumstances. Like fellow Irishman Paul Mescal (in my opinion the finest actor in the world), Claffey makes much of the seeming discordance between his vulnerability and bulk, approaching the role with an open-faced kindness that mutes his strength without ever quite letting us forget it. Playing against Ansell’s Egg, the 29-year-old is by turns stern, forgiving, demanding, compassionate, and brotherly, a combination surely designed to seduce even the hardest-hearted of viewers. Take into account Dunk’s own dour training, amusingly explored in flashback, and the man is practically a saint. Who wouldn’t want to traipse the fields in his pleasant, self-effacing company?

Who, that is, but the squeamish or strait-laced among us? Whereas Game of Thrones signaled its adultness with an unblushing passion for sex, A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms does so with bawdiness, a tone and color more than a little reminiscent of (but obscener than) Monty Python. If scatological humor and mile-long prosthetic phalluses are your bag, you will watch the new series in a state of bliss, understood at last by the people behind the camera. For the rest of us, it is a relief when everyone finishes and zips up. There is, after all, a tournament to be won.

It is only a minor spoiler to say that A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms sends its heroes down more winding paths than the jousting lists. Along the way, they meet such friends or foes as Ser Lyonel Baratheon (Daniel Ings) and Prince Baelor Targaryen (Bertie Carvel), two excellent supporting players who do much to give the action shape and form. As ever, though, the dragon is in the details, and the production’s mastery of those is wonderful to behold. A longtime fan of creator George R. R. Martin’s universe, I have spent many happy hours in Westeros. But I have never felt more at home there.

Graham Hillard is an editor at the James G. Martin Center for Academic Renewal and a Washington Examiner magazine contributing writer.