In Death by Lightning, the new Netflix miniseries helmed by Mike Makowsky of Game of Thrones fame, President James Garfield and his assassin, Charles Guiteau, are opposite poles of the national character, forever united through one of those lurid, violent spectacles for which we Americans have such an enormous tendency and talent. In lesser hands than Makowsky’s, the converging twain of Garfield, portrayed by venerable dramatic wingman Michael Shannon, and Guiteau, played by Succession’s Matthew Macfadyen, might sink into lazy archetypes, producing a cleanly cynical story about how the worst of us is ever hurdling into bloody collision with the best of us. It is Makowsky’s careful shading of what is “best” and “worst” in the American animal that rescues Death by Lightning from any tedious moralism. It is one of the few truly outstanding originals that Netflix has ever made.

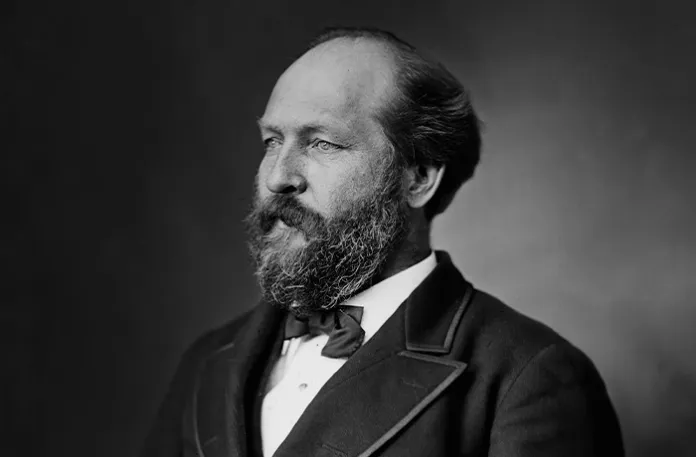

For sheer Americanness, few historical figures top Garfield, briefly our 20th president. He rose from rural poverty to become a heroic Civil War general, an admired congressman, a champion of equality for African Americans, an enemy of political graft, and the commander in chief. His life and career tell us the best possible story about ourselves, at least if you leave out the very end. Our worst image of ourselves, the one we fear to be as true and as compelling as our self-conception of limitless possibility and decency, tells us that there is nothing more American than getting senselessly gunned down by a fame-seeking psychopath.

When Lightning opens in the summer of 1880, Guiteau is an itinerant thief and conman sweet-talking a panel of New York magistrates. Out in the Ohio countryside, Garfield is leaving his adoring wife and children for the Republican convention in Chicago. The 50-year-old congressman and former Union Army officer, hero of the Battle of Middle Creek, has been stuck with the unenviable duty of giving an endorsement speech for the doomed presidential candidacy of Ohio Sen. John Sherman, the pro-reform Half-Breed faction’s obligatory protest against the rival Stalwarts, who back a third term for the corrupt and elderly President Ulysses S. Grant. The lead Stalwart isn’t Grant but the conniving New York Sen. Roscoe Conkling, a tyrannical flim-flammer played with great relish by Boardwalk Empire’s Shea Whigham. Conkling’s power comes from his control over the customs house of the New York City port, the source and physical location of three-quarters of all federal revenue.

Conkling is a human weasel, with only money and power to motivate him. Garfield is serious, retiring, and quiet in private, almost a cipher. He says he does not want to be president, and flies into a rage at the first convention delegate to vote for him. But in Lightning, and perhaps in real life, a presidential character overwhelms any conscious will. In four-and-a-half minutes of scorching convention hall oratory, Garfield summons “a fire of freedom,” speaks to the “immortal pillars of justice and truth,” and dreams of “a man who … embodies all that is good about this place.” Shannon’s Garfield is almost terrified at the power of his rhetoric, at his sudden investment with the charisma of a national leader, and at the realization that he isn’t talking about Sherman but about himself. After a 35-ballot deadlock, Half-Breed leader and Maine Sen. James Blaine cuts a deal with Conkling without Garfield’s knowledge or consent: Garfield will get the nomination if Chester A. Arthur, senior-most Conkling henchman and chief duty collector at the port of New York, is named his running mate. Thus, a handcuffed Garfield is dropped near the apex of American political power without quite knowing how or why he got there. Garfield suspects he’ll be a weak president if he wins in November, hemmed in by Conkling and Arthur, but he tells his wife Lucretia that the presidency is nevertheless “a chance to fix all the things that terrify me about this country.”

Shannon’s Garfield is reserved and proper, an idealist but also a figure of the 19th century. Macfadyen’s Guiteau has the manic quality of a Will Ferrell protagonist, and talks like someone much closer to our own time. Makowsky does not settle on a single interpretation of Garfield’s killer. Maybe he’s an incel — in a flashback, we learn that Guiteau was the only person who couldn’t get laid at John Humphrey Noyes’s utopian sex cult in Oneida, New York. Maybe Guiteau is an obsessive Garfield fan, perhaps the only person who sees the president as something more than a political accident or a tool. “I’m here because I believe in change,” he announces to a roomful of senior Garfield campaign advisers. Perhaps Guiteau is a 19th-century Groyper, a loser who found a twisted political outlet for his lonely rages. “Do any of you have any idea how many more of us there are like me, who have never had a taste for politics till now?” Guiteau bellows at Garfield staffers in the most quietly terrifying line of the series.

One of the show’s best qualities is that it shows how unfair and hostile the world must seem from the perspective of a true psychopath. Every door is shut in Guiteau’s face — every door but one. Guiteau, who spoke at a couple of pro-Garfield rallies, believes he is entitled to a job in the administration and scores a sitdown with the president. This meeting never actually happened, but then again, Prince Hal probably didn’t kill Hotspur in single combat at Shrewsbury either.

“Help me succeed like you did,” Guiteau pleads, shaking and stammering before his hero, whom he will soon see as his one and only enemy. “I’m begging you, tell me how I can be great too.”

“You misinterpret me,” the president replies. “We’re all only men. It is God, not I, who is great and who grants us purpose.”

FEAR ITSELF: REVIEW OF ‘IT: WELCOME TO DERRY’

Here are two American voices, talking past each other. Sadly for us, it is Guiteau’s, the voice of the bitter megalomaniac possessed with a violent belief in his own worth, that our contemporary ears are more attuned to. Garfield is a figure from an ideal world of faith, obligation, and honor. His answer doesn’t satisfy Guiteau, and frankly, it doesn’t really satisfy us either. It’s doubtful that any president of any of our lifetimes has lacked a comprehensive inner theory of their own greatness. Garfield is simply too pure to last, and when he’s shot, he’s too pure not to have to suffer for two months as he’s slowly butchered by the worst of 19th-century medicine.

The synthesis between our story’s two poles is Vice President Chester A. Arthur, played with alternating pathos and bathos by an excellent, atypically wide-ranging Nick Offerman. How many of you have paid any thought to our moustachioed 21st president, butt of an immortal Simpsons joke? Watch Lightning and you, like Lisa, will contract a mean case of Chester A. Arthuritis, a disease as unlikely as the presidency of its namesake. Against all odds, this depressive, boorish drunk, lately a glorified tax collector and political goon, morphs into a real statesman, the president who ended the New York stranglehold on the federal coffers, reformed the U.S. civil service, and began a buildup of the Navy, except that the odds of such transformations aren’t actually so steep around here. “I am not fit to be a president,” Arthur frets to Conkling after Garfield is shot. “That’s the beauty of America, my friend,” Conkling replies. Garfield is the murdered ideal, but the mundane realities of our nation are a wonder unto themselves.

Armin Rosen is a Brooklyn-based reporter-at-large for Tablet Magazine.