Money has shaped the justice system for centuries through common law tort principles that balance financial restitution with moral accountability. But over several decades, that balance has collapsed. Wall Street and other big investors are now allying themselves with trial attorneys to take stakes in litigation outcomes. They have entered the courtroom through third-party litigation funding and accelerated the decline of justice from a pursuit of truth into a profit-driven enterprise.

What began as a system designed to make victims whole has become one in which financiers gamble on corporate risk aversion and human suffering. By stripping away the ethical restraints that once guided tort law, monetized justice has created a moral hazard, turning the courtroom into something between an amoral casino and an extortion racket.

The first steps toward the perversion of our justice system came five years before Saul Alinsky advised community organizers to “pick the target, freeze it, personalize it, and polarize it.” The behavior of many litigation law practitioners is akin to that of Alinsky’s Rules for Radicals, a primer on militant strategy and tactics.

In 1966, the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure were rewritten to create the “opt-out” class action, in which affected people are automatically included as part of a lawsuit unless they withdraw. This rule change opened the door for a new generation of mass tort lawsuits. In Alinskyite fashion, a key strategy was to turn defendants into villains.

Billion-dollar judgments against asbestos, breast implant and contraceptive device manufacturers, among others, followed. Companies were left bankrupt. Thousands of jobs have been lost. And trial lawyers developed a playbook to manufacture new claims.

“Don’t wait for the next big tort. Build it,” Mike Papantonio told the spring 2025 Mass Torts Made Perfect conference. “If you want to build a new project, you better build it around a story, a human story that the average American juror can relate to. That’s where it starts. That’s how you win.”

For decades, trial lawyers had to use their own money to “build” the stories needed to freeze, personalize, and polarize litigation targets. But now, thanks to another set of rule changes, ones imported from overseas, trial lawyers have endless resources to pour into television and social media campaigns attacking their targets. It is called third-party litigation financing. And it has enabled trial lawyers to spend over $131 million on television ads alone targeting Monsanto and its herbicide Roundup. The campaign was so successful that Bayer AG bought Monsanto and retired the name. The Monsanto brand was essentially sued out of existence.

If you went to law school as recently as even a decade ago, the concept of lawyers using money from Wall Street investors to fund litigation sounds like something that ought to be regarded as a per se violation of the Model Rules of Professional Conduct.

Rule 5.4(a) clearly states, “A lawyer or law firm shall not share legal fees with a nonlawyer” except in a number of specifically enumerated exceptions, including the death of a lawyer and sharing fees with a nonprofit organization. Rule 5.4(b) prohibits forming “a partnership with a nonlawyer if any of the activities of the partnership consist of the practice of law.”

Rule 5.4 exists to protect the professional independence of lawyers and thus of the tort system by preventing nonlawyers from exerting control or influence over legal judgment or the attorney-client relationship. By limiting law firm ownership and management to licensed attorneys, the rule is supposed to ensure that lawyers remain accountable solely to their clients and to the quality of their legal work, unaffected by profit motives or business pressures from outside investors. Lawyers are supposed to base their advice entirely on the client’s best interests and the requirements of the law.

A plain-text reading of Rule 5.4 would make third-party litigation financing unethical. But lawyers don’t get paid to follow rules — they get paid to manipulate them for financial benefit to themselves, their clients, and now, their investors. That is exactly what has happened with the regulation of third-party litigation funding over the past 20 years.

The loosening of the rules against third-party litigation started in Australia in the 1990s when the parliament passed a law allowing companies in bankruptcy to accept money from investors to finance the pursuit of preexisting legitimate claims. But the practice quickly leached beyond the context of bankruptcy. In a landmark 2006 case, Australia’s high court allowed third-party investors to finance legal claims of tobacco retailers who had been charged illegal licensing fees by tobacco wholesalers. The court reasoned that since retailers and investors were “of full age and capacity” to bargain fairly, there was no reason to bar such agreements.

The number of class action lawsuits promptly exploded in Australia, increasing by 200%. It is estimated that almost 65% of all Australian class action suits are now financed by investors.

Similarly, in Britain, 1990s legislation permitted contingency fee arrangements between lawyers and clients, a practice long accepted under American common law since the 1800s. British lawyers then began asking why others couldn’t also fund litigation. By the early 2000s, courts began approving third-party funding agreements. By 2009, British litigation finance firms were going public — firms such as Burford Capital listed on the London Stock Exchange through initial public offerings.

The timing was perfect for the burgeoning global litigation-finance industry. As the 2008 financial crisis rendered many traditional investments unprofitable, securitized legal claims offered investors a new and coveted stream of predictable returns. With its business model perfected overseas, Burford pushed the envelope in the United States. Some states, such as New York, had already loosened state bans on third-party litigation financing, and with that foothold in place, billions poured into other states to push their courts into allowing the practice as well.

Minnesota was typical. In 2012, a woman named Pamela Maslowski was injured in a car crash and retained a lawyer to sue the driver. Two years later, Maslowski contracted with a New York third-party litigation funding firm that had offices in Minnesota. She received $6,000 from this firm, Prospect Funding Holdings, in exchange for interest in her claim. The contract entitled Prospect to recover $6,000, a $1,425 processing fee, and 60% annual interest.

When Maslowski settled 14 months later, Prospect demanded $14,108 from her. Maslowski then sued in a Minnesota court, claiming her contract with Prospect was void as a matter of public policy, which it had been at the time under Minnesota law. Prospect tried to get the case removed to a New York court and tried under New York law, where third-party funding was legal. But both the Minnesota and New York supreme courts agreed this would undermine Minnesota’s choice not to follow New York down the third-party litigation path.

Minnesota’s court of appeals sided with Maslowski, holding that as far back as 1897, the state had followed the common law rule of champerty, defined as “an agreement between a stranger to a lawsuit and a litigant by which the stranger pursues the litigant’s claims as consideration for receiving part of any judgment proceeds.”

“The general purpose of the law against champerty and maintenance” is to “prevent officious intermeddlers from stirring up strife and contention by vexatious or speculative litigation which would disturb the peace of society, lead to corrupt practices, and pervert the remedial process of the law,” the appeals court quoted from the 1897 Minnesota case.

“In other words,” the appeals court continued, “the prohibition on champerty and maintenance is aimed at discouraging ‘intrusion for the purpose of mere speculation in the trouble of others.’”

Prospect appealed to the Minnesota Supreme Court, a body whose seven justices were all appointed by Democratic governors. Trial lawyers are among the most generous money donors to Democratic politicians. The Minnesota Supreme Court, stacked with Democratic nominees, overruled more than 100 years of precedent because “societal attitudes regarding litigation have also changed significantly.”

The majority reasoned, “Many now see a claim as a potentially valuable asset, rather than viewing litigation as an evil to be avoided,” noting that the size of the litigation financing industry had already grown to $100 billion in jurisdictions where it was legal. “It is also possible that litigation financing, like the contingency fee, may increase access to justice for both individuals and organizations,” the court continued, although it offered no empirical evidence to support the claim that Minnesotans lacked access to the justice system.

The Minnesota Supreme Court dismissed worries that third-party litigation funding would increase lawsuits. “It is also unlikely that companies like Prospect will fund frivolous claims because they only profit from their investment if a plaintiff receives a settlement that exceeds the amount of the advance — an unlikely result in a meritless suit,” the court wrote. “Litigation financing companies have claim valuation procedures to avoid this very problem.”

This is either an intentionally obtuse or alarmingly naive statement. One can debate when exactly a claim becomes “frivolous,” but the amount of money lawyers have to file such claims is, of course, a factor. If a lawyer is considering taking a client on a contingency basis on which the client only has a 10% chance of winning $100,000, and the lawyer estimates it will cost him $10,000 to win the case, the expected value of such a case ($100,000 x 10% = a $10,000 probable payout compared to the $10,000 litigation cost) would be zero.

But with hedge fund money, the lawyer could find many more similar clients, and since the issues would be similar, the math changes. With an upfront investment from a third party, the lawyer can find 100 clients with similar claims and similar payouts, but now his litigation cost per client is down to $5,000. Economies of scale turn what was a frivolous case not worth pursuing with one client into a $500,000 profit opportunity; (the expected payout of the 100 cases would be $1,000,000 total with a litigation cost of just $500,000).

This is what we see in third-party litigation funding. In 2022, 70% of third-party litigation funding went to mass tort portfolios. Thanks to third-party funding, American courts are being flooded with long-shot, low-merit cases that would not have been brought in the past.

Once Wall Street got a taste of the profits possible from third-party litigation funding, finding existing cases to latch on to wasn’t enough. New harms needed to be created to meet investor demand.

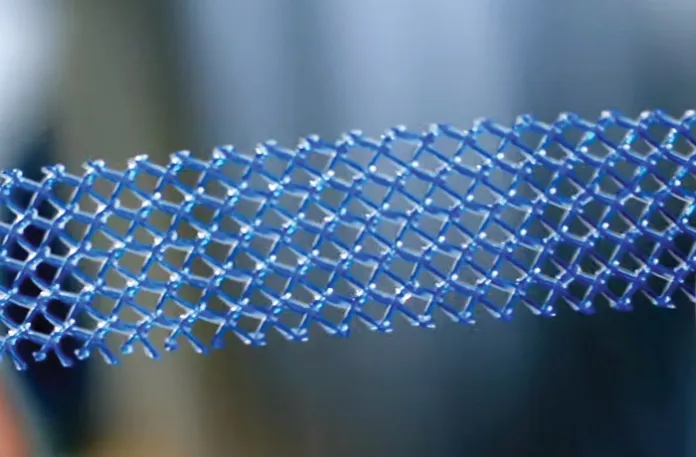

In 1996, Boston Scientific became one of the first medical device companies to secure Food and Drug Administration approval for pelvic mesh implants designed to support weakened pelvic tissue in mothers after childbirth. Johnson & Johnson secured approval for its device in 1998.

These devices were successful for most women, but about 15% did experience nonlethal health problems associated with them, and in 2013, the manufacturers started to defend claims in court.

Plaintiff lawyers quickly discovered that women who had the devices surgically removed received far higher settlements than those who did not. Third-party litigation funders saw a profit opportunity and swooped in, financing extensive marketing and recruitment efforts to recruit new plaintiffs and push them into surgery without consulting their primary doctor.

Mothers with the device received cold calls from marketers who had obtained detailed reports of their medical history. They were promised big payouts if they flew to faraway cities to have their devices removed, even if they had not complained to their primary physician. “Scaring a patient who has limited to no symptoms into removal is just dangerous and irresponsible,” Dr. Victor Nitti told the New York Times.

But that is exactly what the third-party litigation funding industry was doing. Thousands of women from across the country were given cash up front to undergo unnecessary surgery, only to be hit with a big bill from financing firms once the medical device firms paid out. The lawyers scored big and no doubt bought themselves yachts and homes in the Caribbean. Investors also made a killing. But the mothers were often left with far less cash at the end than they originally thought they would receive.

Creating and maximizing harm for profit is not the only bad behavior third-party litigation funders have brought into our justice system. They are also taking litigation decisions away from clients, discouraging settlement, and prolonging litigation.

When the wholesale food distributor Sysco Corporation sued beef, pork, and poultry processors for antitrust violations in 2019, its lawyers suggested signing an agreement with the world’s largest third-party litigation financier, Burford Capital, to help finance its claims. After Burford invested more than $140 million in the suit, Sysco began to receive settlement offers and wanted to accept them. But Burford did not.

After Sysco attempted to accept settlement offers from defendants, Burford sued Sysco to enjoin them from finalizing settlements, and an arbitrator sided with Burford. A federal court later found that not only did Burford want to prevent settlement so it could maximize profits in the Sysco litigation, but Burford also had other investments in similar cases. If Sysco were to settle for what Burford considered too little, it would not only lower Burford’s returns in that case but would also do the same for all the other antitrust cases in its portfolio. This is exactly the type of harm the common law rule against third-party funding, which Minnesota’s Supreme Court casually tossed aside, was designed to prevent.

Perhaps the greatest potential for harm from third-party litigation funding comes from overseas. Not only could a malicious foreign actor such as China use third-party litigation funding to impose costs on U.S. competitors, but through the litigation system’s discovery process, it could gain access to sensitive intellectual property and trade secrets.

That appears to have happened already in one case in which Delaware Federal District Court Judge Colm Connolly made it a standing order in his court for plaintiffs to disclose any third-party litigation funding agreements. Because of Connolly’s order, an American firm called Staton Techiya disclosed that its patent case against Samsung Electronics was being funded by the Chinese government-controlled PurpleVine IP. Multiple plaintiffs have since pulled their cases from Connolly’s court because they did not want to reveal their foreign funding sources.

“Third-party litigation financing is not a traditional investment. It does not produce anything. It just generates litigation. It takes bets on the outcome of litigation, with the investors counting odds,” George Mason University Antonin Scalia Law School professor Donald Kochan recently testified before Congress. “This kind of influence fundamentally changes traditional dynamics in the litigation system. It is the casino-ification of our civil justice system.”

“Courts should not become just a playground for investment and gambling,” Kochan continued. “We need to maintain a civil justice system outside the market if we are to preserve the civil justice system as a predictable, neutral, and accessible system that serves the market. In order to preserve the effectiveness of our nation’s courts to serve as necessary and neutral forums that facilitate the market, the court system must be insulated from market forces.”

Ideally, Congress would take action to ban third-party litigation financing from our courtrooms. The justice system functioned fine without it for over 200 years. We can easily go back to forcing lawyers to finance their own lawsuits. Unfortunately, none of the legislation currently in Congress would do that.

Legislation has been written but not passed, and it focuses more on creating transparency in the industry through reporting requirements and closing some tax loopholes enjoyed by third-party financiers. Rep. Darrell Issa’s (R-CA) Litigation Transparency Act would require all parties in federal civil cases to disclose any third-party funding agreements. Meanwhile, Sen. Thom Tillis (R-NC) and Rep. Kevin Hern (R-OK) have introduced the Tackling Predatory Litigation Funding Act, which imposes a tax on profits received by third-party funders from litigation, effectively treating them as ordinary income rather than capital gains.

If we are going to allow third-party litigation financing, a reporting requirement is absolutely essential. How are judges supposed to make decisions about what discovery requests are reasonable if they don’t even know the true resources available to each party? How are they supposed to determine if a class action settlement is fair if they don’t know all the parties with a financial interest in the case?

But why accept and normalize this corruption of the legal system? Third-party litigation financing does not create or produce anything of value, even though it generates billions of dollars for predatory lawyers and their financial backers. It certainly does not make our country any more just. It is a parasitical practice draining vitality from the economy and eroding our justice system, sometimes at the behest of foreign entities. Why is this tolerated at all?

There is, of course, no reason to trust either Congress or the courts to fix a system that encourages that traditional species known as “shyster lawyers.” Many members of Congress, principally the Democrats, are helped to stay in their jobs because of donations supplied by the plaintiffs’ bar. And it was the courts that created the problem in the first place, partly by lumping cases together in class actions to deal with them all faster, and partly when many judges are elected and suffer the same conflicts of interest as do members of Congress.

THERE IS NO FIRST AMENDMENT RIGHT TO DOX LAW ENFORCEMENT

Democrats have always been the favored political party of trial lawyers, and the same is true of third-party litigation financing firms. Burford Capital, the world’s largest third-party litigation financier, gave almost $100,000 to Democrats in the 2024 cycle, including to then-Vice President Kamala Harris’s campaign. The money Wall Street pours into third-party litigation financing is thus used first to take money away from productive investments by American companies, and then it is funneled to lawyers and financiers, and then some of it is given to the Democratic Party. It is a cycle of corruption and waste. It should be banned entirely.

In the end, third-party litigation funding is not justice. It’s Saul Alinsky’s playbook with Wall Street’s bankroll. What Alinsky once urged activists to do — “pick the target, freeze it, personalize it, and polarize it” — is now the business model of modern trial lawyers and financiers. Lawsuits are no longer about truth or fairness but about turning companies into villains to extract settlements. Hedge funds bankroll the outrage, lawyers craft the narratives, and juries are the weapons. Foreign powers exploit the same tactics to wound U.S. firms and steal their secrets. This isn’t justice — it’s organized, monetized activism. Congress should end it, not mend it.

Conn Carroll is the commentary editor of the Washington Examiner.