In Focus delivers deeper coverage of the political, cultural, and ideological issues shaping America. Published daily by senior writers and experts, these in-depth pieces go beyond the headlines to give readers the full picture. You can find our full list of In Focus pieces here.

Lawmakers in Washington are sounding the alarm over little-known shareholder watchdogs that they say are quietly shaping decisions at the nation’s largest companies.

The two players at the center of the storm are Institutional Shareholder Services and Glass Lewis, which dominate nearly the entire proxy advisory market. Both companies play an outsize role in guiding how major institutional investors such as BlackRock, Vanguard, and State Street vote on everything from executive pay and board seats to hot-button policies tied to climate policy and workplace diversity.

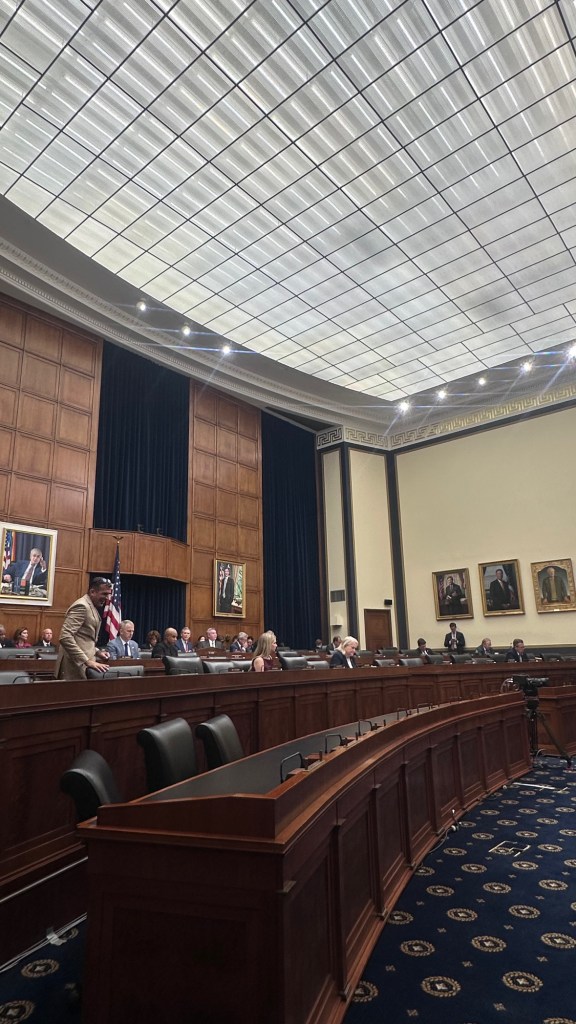

What started as a simple “cheat sheet” for busy investors has, according to critics, morphed into a system where ISS and Glass Lewis effectively steer corporate decision-making. That influence boiled over at a heated House hearing last week, where Republicans accused the firms of acting like unelected regulators.

Much of the fight centers on Rule 14a-8 of the Securities Exchange Act, which lays out the process for shareholders to put proposals on a company’s proxy ballot. Republicans say the rule has been stretched far beyond its intent, enabling activists to force votes on divisive social issues that have little to do with shareholder value. Democrats counter that 14a-8 is one of the few tools ordinary investors have to hold corporate boards accountable.

Rep. French Hill (R-AK), who chairs the House Financial Services Committee, argued the firms’ influence has ballooned in recent decades, raising doubts about whether they still serve investors.

“We’ve seen the shareholder proposal process diverted away from the critical business strategy focus and instead become a tool for advancing proposals to distract from companies’ missions, leading to an erosion of shareholder value and costly burdens on companies,” Hill said during the hearing on Wednesday.

Other Republicans piled on, saying the proposal process has been hijacked. Rep. Marlin Stutzman (R-IN) pointed out a Cummins proposal to link executive pay to climate goals, a diversity, equity, and inclusion data-reporting resolution at Eli Lilly, and a request at Coca-Cola for a report on the risks the company faces from state abortion restrictions. Rep. Lisa McClain (R-MI) was more blunt: “Two proxy firms should not be deciding how trillions of dollars in shareholders’ votes are cast.”

Shareholder activism has already left its mark on some of the country’s best-known companies. After repeated pressure from investors, Amazon agreed to conduct a racial equity audit of its workforce practices, a move overseen by an outside law firm. Tesla’s $56 billion pay package for CEO Elon Musk became another flashpoint, with both Glass Lewis and ISS urging shareholders to vote it down. Another corporate heavyweight, JPMorgan Chase, faced proposals demanding more detailed disclosures about its fossil-fuel financing, while companies such as Coca-Cola and McDonald’s have been pressed on workplace policies ranging from abortion access to gender-affirming care.

Stutzman said the trend underscores how a small group of activists can use proxy firms to drive corporate agendas.

“I’m a free market guy, and I believe companies need to be able to pursue their mission, not be socially directed by a small group of shareholders,” he told the Washington Examiner. “These firms are the ones that are the real financial winners, and the companies are the ones that have to navigate issues they don’t really want to deal with.”

Critics warn that big asset managers can push companies into cultural fights. BlackRock, which owns nearly 15% of Cracker Barrel, often follows guidance from ISS and Glass Lewis. Last month, the chain dropped its famous “Old Timer” logo for a new look, drawing fierce backlash from customers, conservative critics, and even President Donald Trump. Within weeks, Cracker Barrel reversed course.

“If they want to rebrand themselves and say, ‘This is who we are,’ fine. But customers will let them know very quickly if they don’t like it,” Stutzman said, noting that Jaguar Land Rover’s CEO faced similar criticism, stepping down after a rebrand critics derided as “woke.”

Democrats countered that Republicans exaggerated the firms’ sway and misrepresented how the shareholder process works. Rep. Sean Casten (D-IL), former CEO of Turbosteam Corporation, dismissed the hearing as “really dumb” and accused Republicans of inventing a “boogeyman that doesn’t exist.” He stressed that shareholder proposals are strictly advisory, not binding, and said it was misleading to suggest proxy advisers could dictate corporate decisions.

“Shareholders are actually the people who own companies … executives serve at their pleasure. They are custodians of shareholders’ investment, but they are not actually the people in charge,” Casten said. “This is not freaking complicated … the law says [shareholder proposals] are advisory. They get factored in, and then we have a high-functioning board.”

New York City comptroller Brad Lander, who testified as a witness, emphasized that shareholder proposals are essential tools for accountability and long-term value. Lander, who oversees $300 billion in pension assets, pointed to past campaigns on executive pay clawbacks, insider trading, and board access that began as shareholder resolutions and later became standard practice or Securities and Exchange Commission policy.

“These tools help protect the retirement security of New York City’s teachers, cops, firefighters, and nurses,” he said. “Shareholder proposals and engagement strengthen accountability and ensure that U.S. markets remain the most trusted and resilient in the world. Let’s not screw that up.”

Lawmakers also raised alarms about who owns the proxy advisory giants. ISS, founded in Maryland in the 1980s, is now majority-owned by Deutsche Börse Group, the German exchange operator that runs the Frankfurt Stock Exchange. Glass Lewis was acquired in 2021 by Peloton Capital Management, a Toronto-based private equity fund. The two firms control about 97% of the U.S. proxy advisory market.

Rep. Warren Davidson (R-OH) questioned why such influential players have never been reviewed by the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States, which screens foreign takeovers for national security risks.

“In a world where we’re laser-focused on foreign influence in critical sectors like tech and infrastructure, why aren’t we properly screening foreign companies that control corporate governance in our country?” he asked, warning that European or Canadian ownership could import different political priorities into U.S. boardrooms.

Witnesses echoed those concerns, pointing to the influence of European-style “double materiality” standards, which consider both a company’s effect on the outside world and on shareholders, in proxy adviser recommendations.

“They’re inappropriately importing European standards of investing into the standards they are then imposing in the recommendations they give to companies … applying an entirely different investment theory to U.S. companies,” said Ferrell Keel, a partner at Jones Day.

Ron Mueller of Gibson Dunn added that the shareholder proposal process has become professionalized, with advisers “not just asking for information. They’re trying to influence outcomes.”

The firms reject the charge that they wield unchecked power. ISS pushed back on the criticism, stressing that it does not control which proposals appear on corporate ballots or how investors ultimately vote. “Corporations and their investors … make those choices,” a spokesman said in a statement to the Washington Examiner, adding that ISS provides “rigorous, fact-based research, analysis, and recommendations” based on clients’ voting policies. The firm also noted that it is registered with the SEC under the Investment Advisers Act and said a framework for regulating proxy voting advice already exists. Glass Lewis declined to comment.

The debate over how to check that influence now shifts to regulators and the courts. Federal regulators have wrestled with how far to go in policing the industry. In 2020, the SEC adopted rules aimed at adding transparency and giving companies a chance to rebut proxy firm recommendations. Two years later, former SEC Chairman Gary Gensler reversed course, rolling back those measures. More recently, a federal appeals court narrowed the agency’s reach even further, ruling that proxy advice does not count as a “solicitation” under federal law, a decision that limits the commission’s ability to regulate the firms.

States have tried to wade in as well. In Texas, a new law requiring proxy advisers to disclose when their recommendations relied on “non-financial factors” such as environmental, social, and governance considerations was set to take effect Sept. 1. However, on Aug. 29, a federal judge granted ISS and Glass Lewis a preliminary injunction, siding with their argument that the statute violated the First Amendment by compelling speech, among other claims.

A source familiar with the agency’s thinking said legislative changes that explicitly authorize the SEC to regulate proxy advisers under the Exchange Act would be the most effective fix. SEC Chairman Paul Atkins has long been critical of proxy firms, and the source added that the commission shares lawmakers’ and industry groups’ concerns about the firms’ influence and lack of accountability.

LAWMAKERS DEMAND OVERSIGHT OF PROXY GIANTS DRIVING ESG IN CORPORATE AMERICA

That tug-of-war has sharpened calls in Congress for a legislative fix, especially after recent court decisions. Rep. Bryan Steil (R-WI) told the committee he has repeatedly introduced bills to rein in what he called the “duopoly” of ISS and Glass Lewis, arguing both firms should be held to stricter disclosure standards. Rep. Ann Wagner (R-MO) promoted her Corporate Governance Examination Act, which would require the SEC to study the proxy process regularly to guard against what she described as “unnecessary politicization.”

But Lander cautioned that rolling back shareholder rights would backfire. He noted that past proposals helped drive reforms later codified by the SEC. New limits, he warned, could “gut” accountability tools that protect long-term investor value.