The dishwasher was made in America, though there is some dispute over who did it. That’s because there are two rival American inventors of the dishwasher, with dueling patents. Credit comes down to which model of creation you find more persuasive: genius or tinkering.

The genius was a man named Joel Houghton, who invented and patented a mechanical dishwasher in 1850. The tinkerer was a socialite and widow named Josephine Cochrane. Though she consulted Houghton’s design and had help with her own model, it was arguably her insights and persistence that made dishwashers a success.

The perhaps slightly embellished sales pitch went that after a party in Cochrane’s home in the 1870s, she noticed that far too many of her dishes were chipped from servants attempting to clean them. She tried to cut replacement costs by taking matters into her own hands at the kitchen sink. While working through those dishes, she thought, as so many have thought over the years, that there must be a better way to do this.

Cochrane’s upbringing may have played a role in her belief that getting away from the hand-washing of dishes could be anything more than a soap dream. She had a civil engineer father who built bridges in Ohio. “Cochrane, thus, may have had creative tendencies in her family,” explains a biography of her on the website of the Lemelson-MIT Program, which aims to incubate future inventors.

The MIT bio goes on to admit that Cochrane “was not formally educated in the sciences” and that she knew as much. She brought in a mechanic and eventual business partner, George Butters, to help design, prototype, and later run the factory for her dishwashers.

Cochrane applied for the patent on the final day of 1885 and was granted it just after Christmas the following year. “My invention,” she wrote on the application, “relates to an improvement in machines for washing dishes, in which a continuous stream of either soap-suds or clear hot water is supplied to a crate holding the racks or cages containing the dishes while the crate is rotated so as to bring the greater portion thereof under the action of water.”

American society took notice in a hurry. Cochrane, an Illinois resident, entered her dishwasher at the World’s Fair in Chicago in 1893. It took home a blue ribbon for “best mechanical construction, durability and adaptation to its line of work.”

The Daily Picayune of New Orleans effused that “women of the future” would remember Cochrane fondly, for she had set them “free from the most slavish and disgusting task of housekeeping — dishwashing.”

Finding a market

Smart technology dishwasher manufacturer Candy highlights similarities between the Houghton and the Cochrane dishwashers in its own potted history of the device. Both were initially hand-cranked and sprayed water on the dishes inside some sort of chamber. With Houghton’s dishwasher, the chamber was a wooden barrel.

Yet only the Cochrane dishwasher, with a low-set circular design that resembled a metal still, bothered to heat that water and spray it at the dishes with some velocity, as a sort of pressure washer. Those changes made it more “functional” than its predecessor and, thus, more sellable — to the right buyer.

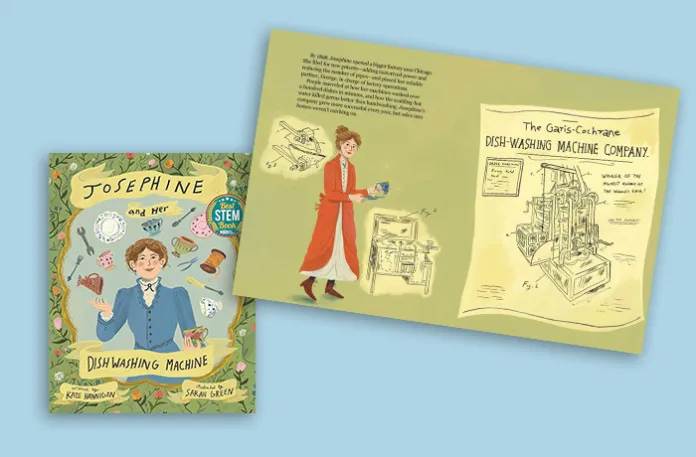

The engaging children’s book Josephine and Her Dishwashing Machine, written by Kate Hannigan and illustrated by Sarah Green, admits that while “orders began pouring in from hotels, restaurants, and even schools and hospitals,” with continuous growth in the commercial space, “sales into homes weren’t catching on.”

The price point was high, which held sales back. Cochrane’s machines sold for about $800 per unit around the turn of the 20th century. That would be somewhere between $25,000 and $30,000 per unit in today’s dollars. Very few households, then or now, could afford that kind of sum for an appliance, even if it did save on time, chipped dishes, and skincare.

When Cochrane died in 1913, at 74, from complications following a stroke, there was a growing commercial market for dishwashers in the United States. It did not yet add up to a mass market, however, thus manufacturer Candy’s contention that Cochrane’s dishwashers enjoyed only “moderate success.”

“Josephine didn’t worry” about that but rather worked to improve her product continuously for a future when households could buy in on a large scale, Hannigan argues. “It is a good world, and getting better every day,” Cochrane is quoted as saying before the jump to our present, more luxurious moment.

“Eventually her dream of dishwashers humming in home kitchens came true,” Hannigan writes, with colorful illustrations of several uses of clean china in the background as an inviting proof of concept. “Instead of standing elbow-deep in the sink, women and men and even children had more time to do the things they loved,” such as flower picking and cake frosting. And we had Cochrane’s tinkering largely to thank for it.

A sudsy dream, still

But not so fast, Pollyanna. Liberation from time and pruning through mass dishwasher ownership is a dream that remains only partly fulfilled. And the U.S. government may be one of the culprits holding it back through a regulatory ratchet that could make your plates spin.

A survey of the U.S. Energy Information Administration from 2015 compared dishwashers with other major home appliances, including microwaves, stoves, and clothes washers and dryers. It found that dishwashers “are both less pervasive and less likely to be used when available.”

Of the 80 million U.S. households that had dishwashers at the time, “16 million (almost 20%) did not use their dishwasher,” the agency found. In total, “a little more than half (54%) of all U.S. households both have a dishwasher and use it at least once a week.”

That is a curious gap between ownership and usage that was unmatched by other appliances. Microwave ovens, which came along much later, enjoyed more widespread ownership and usage, both above 90%, in spite of urban legends about how microwaves will explode your pets and lower sperm counts.

Why would so many people have home dishwashers but not use them? There are three main explanations for that gap, and the first two are nonpolitical. The first reason has to do with how the U.S. government defines “households.” Singles who live alone and technically count as households often have more disposable income. Many of these people are more likely to eat out for most of their meals, which means little to no running of the dishwasher.

Yet a surprisingly large number of dishes that are washed end up being washed by hand. One report by green energy consultant David Jagger for Energy Solutions weighs in on why that might be so: “The reasons for hand-washing when a dishwasher is available vary, but cultural differences, distrust in technology, and personal preference are often cited.”

Our second reason for the dishwasher gap, “cultural differences,” might strike many as an odd one for not using a dishwasher, at least on a larger scale in present-day America. Still, while looking into the claim, I talked with Maria Simpson, a Democratic political strategist from Virginia. One does not divulge a woman’s age, but she’s my rough contemporary, and I’m 46.

Simpson shared a story from her childhood in the U.S. as a second-generation American. “My father was an immigrant from Europe,” she told me. “When he saw that our house had a dishwasher, the first thing he did was forbid us kids from using it.”

Her father banned dishwasher use because he “genuinely believed that allowing his children to use household appliances would make us lazy, so he made us do all dishes by hand,” she said. These days, she loves her dishwasher and said the “sight of a sponge and dish soap is repulsive to me.”

Asked in a follow-up question if she considers Cochrane an entrepreneurial proto-feminist hero, Simpson texted back that she was driving and wrangling a child at that very moment, but, “Good God yes.”

Dishwashers around the world

The American dishwasher experience differs in degree from the rest of the world. Somewhere between 70% and 80% of U.S. households own a dishwasher, even if many of them do not use it regularly. In many other countries, a far greater percentage of households do not even have that option yet. Though the gap is closing.

Former Florida restaurateur and expat Jeff Eicher reminded me of this while I was interviewing him about the commercial end of dishwashing. He remarked, “It’s funny you should bring this up since there are very few dishwashers in private homes here in Panama,” where he lives. With very few exceptions, “dishwashers are not installed in even the larger homes. No disposals either.” He added, “I have to admit that I miss that convenience.”

Cochrane’s company played a part in making America the world leader in spreading her mechanized convenience to the masses. After her death, the company was acquired by KitchenAid, now a part of the larger Whirlpool Corporation that manufactures dishwashers on a large scale. It had sales last year of $16.6 billion for all appliances.

Overall, there is a robust market with rising demand for dishwashers worldwide. Estimates diverge on the exact size of the market, but they agree that current sales come to tens of billions of dollars every year.

However, here’s a fun experiment: Take a country such as the United Kingdom and try to guess the percentage of households that have dishwashers. That figure is currently just above 50%, extrapolating from available data. (It had ownership at 49% in 2018, up from 18% in 1994, according to Statista.)

Chalk part of the worldwide trend up to price. Global incomes are coming up, and this is increasing the purchasing power of billions of consumers. The price of dishwashers, along with most appliances, has seen a long-term, shallow downward trend, making such purchases even more affordable.

How affordable? Whereas the first dishwashers would have run $25,000 or more in today’s dollars, you can now buy a countertop model for $250, a hundredfold decrease in price, or a standard 24-inch wide model for $400, according to the website HomeGuide. Installation costs are also typically fairly low.

Restaurants conquered

The story of the dishwasher tracks well with the general story of technological progress, but only up to a point. You have the inventor creating the thing, refining it, and selling it to high-rolling early adopters who are willing to take a chance and pay a premium. You also have larger market adoption that follows, though there are still some difficulties to be worked out at that stage.

Most early adopters of dishwashers were institutions such as restaurants that could turn that investment into savings on labor costs, product loss, and time management. It took fewer people to run the dishes than to wash them by hand, the dishes would last longer, and the whole thing was over and done quickly, which could cut down on the size of the dish stockpile needed to pair with food.

Even today, restaurants are significantly more likely than residences to have dishwashing machines — and use them. Those industrial-grade ones are both costlier and bulkier than domestic models.

“A typical restaurant dishwasher setup involves a conveyor-type machine” that uses “lots of water,” Eicher informed me. He has been out of the restaurant game for 10 years but used to own three restaurants — Bergamo’s, Charlie’s Lobster, and La Grille — and has kept his eye on industry trends.

“Nowadays, most operators use cold water machines with a chemical disinfectant rinse,” which covers most dishes. However, Eicher said the “best of these still leave spots and an odor that is unacceptable for wine glasses,” which is why many barkeeps do those by hand.

He reckoned that “hot water systems are much better, but they are more expensive to run” and added that “because health inspectors require the first run they measure to be at high temperature, you have to run a booster heater at the dish machine.”

The price for commercial dishwashers runs from the low thousands of dollars to tens of thousands of dollars, depending on the size and complexity of the dish problem the machines are supposed to tackle. Commercial dishwashers also make quite the racket. “Since they are open on the two sides the conveyor runs through, you really have to make sure the restaurant is designed to not have the installation near any dining room door,” Eicher said.

The retired restaurateur admired the efficiency of these machines, which “can run a full rack in a couple of minutes,” but balked at the prospect of ever installing anything like that in a home. The machines are loud, require “constant attention,” and “produce very high humidity in the space in which they operate,” he warned.

Still, commercial dishwashers continue to deliver something like the experience of Cochrane’s first dishwashers, which was deftly captured by Hannigan: “People marveled at how her machine washed over a hundred dishes in minutes, and how the scalding hot water killed germs better than hand-washing.”

Still stuck on rinse

Yet the mass adoption of Cochrane’s miracle machine has slowed in its birthplace in recent decades, and the question nags: Why? Enter politics, of the regulatory variety.

Recall that “distrust in technology and personal preference” were two reasons people gave to green energy consultant Jagger for hand-washing instead of using their dishwashers. In many cases, the two reasons amount to the same thing, with the same cause.

When it comes to washing dishes, many people prefer to brute-force it by hand because they don’t trust the technology, and in most cases, not for some arbitrary reason. They don’t trust the technology because it has gotten relatively worse.

“An older model dishwasher will use approximately 10 to 15 gallons (37.8 L to 56.7 L) of water per load,” explained Home Water Works, a project of the Alliance for Water Efficiency, whereas newer dishwashers use “3.5 gallons or less per cycle.”

Home Water Works chalks the reduction in water usage up to “technological advances,” but regulations have played a large role in the decline of water volume. Four rules passed by the U.S. Department of Energy between 1987 and 2012 ratcheted the amount of water that could be used per load ever downward, and the Biden administration proposed a fifth rule.

If all this rulemaking simply meant lower water usage, consumers would likely cheer at the lower water bills. However, the price, according to many users, has been dishes that aren’t as clean after demonstrably longer cycle times. “Dishwashers used to wash all the dishes in under one hour,” Jeffrey Tucker complained, writing in the Daily Economy. “Now they take two hours, three hours, and four hours, and still don’t get the dishes clean.”

Boosters dispute the decline in dishwashers, but their case is a weak one. “New dishwashers have energy-saving technology, AI-based washing cycles, and IoT-activated features that attract consumers with a high degree of technological affinity,” reports Renub Research in a bullish survey of the global market for dishwashers.

Modern dishwashers have more digital bells and whistles than predecessor models, granted. Some technology geeks may indeed be attracted to these features, though there are trade-offs here, and steep ones, as many normies will also find these features absolutely infuriating.

Some allegedly smart dishwashers need an app to start them. Misplace your phone, and good luck getting those dishes done in time for that party. Other dishwashers (from experience) can lock you out if you accidentally brush up against the wrong series of buttons, and force you to go spelunking through internet forums to figure out how to unlock the bloody thing.

Dishwashers of the future

There may yet be hope of a better, sudsier future for dishwashers. There is, first of all, good evidence that the worst of it has passed, at least when it comes to regulations.

A decision in early 2024 from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit, Louisiana v. U.S. Department of Energy, came in response to a suit that 12 state attorneys general brought against the Biden administration’s Department of Energy. The judges were not kind to the DOE rules for dishwashers and other appliances.

Among other things, the three-judge panel ridiculed the DOE’s argument against standing as a new “Government-always-wins rule,” speculated it was “unclear that DOE has statutory authority to regulate water use in dishwashers” in the first place, and further found that the DOE’s initiatives to conserve electricity and water through restricted usage per load had overwhelmingly backfired.

The judges found that the standards “make Americans use more energy and more water for the simple reason that purportedly ‘energy efficient’ appliances do not work. So Americans who want clean dishes or clothes may use more energy and more water to preclean, reclean, or hand-wash their stuff before, after, or in lieu of using DOE-regulated appliances.”

This ruling came at roughly the same time last year as the slim GOP majority in the U.S. House of Representatives was trying to make hay with what Republicans called “appliance week.” This was a week dedicated to the passage of several bills that would ease regulations on prominent appliances. Bills include the Stop Unaffordable Dishwasher Standards Act, aka the SUDS Act, the Refrigerator Freedom Act, the Liberty in Laundry Act, and the Hands Off Our Home Appliances Act.

Eventually, the bills all passed the House and were passed onto the Senate, where they all died a quiet death in the Committee on Energy and Natural Resources, now run by Sen. Mike Lee (R-UT). That was more or less expected. The point at the time wasn’t to make the change but to make way for change in the event that Republicans ended up in control after the November elections, which is what ended up happening. In his second, nonconsecutive term, President Donald Trump didn’t waste time pursuing a strategy critics derided and boosters cheered for called “Make Dishwashers Great Again.”

THE CARJACKING HEARD ROUND THE WORLD

Trump signed an executive order on his first day declaring it the policy of the U.S. to “safeguard the American people’s freedom to choose from a variety of goods and appliances, including but not limited to lightbulbs, dishwashers, washing machines, gas stoves, water heaters, toilets, and shower heads, and to promote market competition and innovation within the manufacturing and appliance industries.” He followed that with another executive order in May that would roll back water usage restrictions.

The president had tried something similar in his first term, but it came late in the day and was rolled back by the Biden administration before manufacturers could crank up production. This time, consumers are likely to get a crack at buying higher-powered, water-guzzling dishwashers before the next president is ushered into office.

Jeremy Lott is the author of several books, most recently The Three Feral Pigs and the Vegan Wolf.