It goes without saying that Abraham Lincoln was one of America’s greatest presidents. The strengths he brought to the job included intelligence, inspired leadership, unmatched rhetorical power, and a steady hand in dire times. No political leader is perfect, of course. Lincoln made mistakes during his astonishing journey from a small log cabin near Hodgenville, Kentucky, to the White House. But his quest and determination to ensure that people from all walks of life had freedom, liberty, and the ability to pursue the American dream remains a constant source of inspiration and admiration.

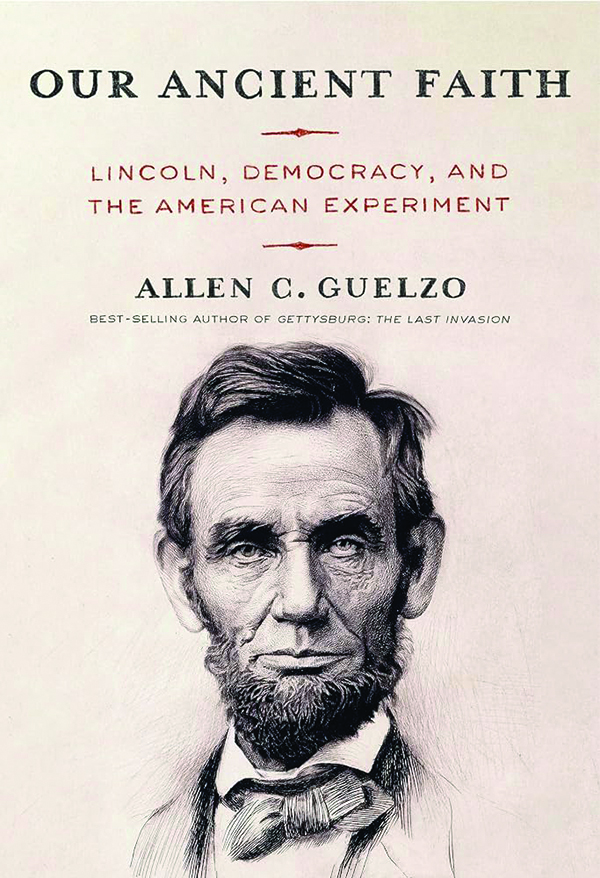

“Generations have looked up to him as the man who not only preserved the Union,” another great president, Ronald Reagan, said on Lincoln Day on Feb. 12, 1984, “but helped us realize that true democracy is an evolving process.” Today, with various groups fighting over how to “strengthen democracy” or claiming that “democracy is on the ballot,” even as they cheapen the common understanding of what the word even means, it is more important than ever to look to history to understand this political concept. And here, the insights of the wise, self-educated, small-town Illinois lawyer about democracy can serve as a crucial guide. In his new book, Our Ancient Faith: Lincoln, Democracy, and the American Experiment, Allen C. Guelzo shines a new light on Lincoln’s powerful vision for true democracy.

Guelzo, a Princeton University historian, is one of the world’s foremost scholars on the 16th U.S. president and Civil War. He has authored 16 books, including Abraham Lincoln: Redeemer President and Lincoln and Douglas: The Debates That Defined America. A three-time recipient of the prestigious Lincoln Prize, he is often included in panel discussions and documentaries focusing on Lincoln’s life and career.

“The word democracy only occurs 137 times in the collected writings of Abraham Lincoln,” he points out. That’s not a significant tally for someone as prolific as Lincoln. Yet what Lincoln said about democracy stands out. “No other word described what he saw as the most natural, the most just, and the most enlightened form of human government,” Guelzo wrote. “Nothing, he said, could be ‘as clearly true as the truth of democracy.’ And nothing demonstrated that truth more clearly in Lincoln’s mind than the American democracy, which embodied ‘the greatest living principle of all democratic representative government.’”

Several themes from Lincoln’s body of work tie directly into the growth and development of democracy, which he once described as “my ancient faith.” In a chapter related to human liberty, Guelzo examines Lincoln’s important distinction between slavery and democracy. This was to illustrate what he believed “democracy was not, and that contrast hinged on the point of consent.” In other words, consent was a duality of “how sovereignty was exercised” and “what drew a line of separation between freedom and enslavement.” Slavery was forced upon black people, who were treated as inferiors and unequal in a country that was supposed to promote equality and equal opportunity. Lincoln correctly understood that consent “was exactly what was absent from the slave’s labor, either at its beginning or ending.” What made slavery wrong, to Lincoln, was then exactly what made it undemocratic: “The master not only governs the slave without his consent; but he governs him by a set of rules altogether different from those which he prescribes himself.”

Chapters concentrating on democracy and race, as well as democracy and emancipation, cover some unusual and controversial topics involving Lincoln. Guelzo, for instance, elaborates on the bizarre phenomenon known as “Thirteentherism.” Some black and African scholars actually don’t believe Lincoln was the Great Emancipator who freed the slaves. Rather, he’s often “condemned as a racist whose interest in freeing American slaves was dictated purely and cynically by his desire to reunite the American Union and who included not just blacks but ‘Indians and Mexican greasers’ in his catalogue of unwanteds.” Their position is unfounded, and Guelzo swats it away as “one of the greatest shifts in historical self-consciousness that has occurred in American life.”

When it came to the abolitionist movement, Lincoln once told his friend John Roll that he was “mighty near one.” Yet during his debates with Stephen Douglas in the 1858 Senate election in Illinois, all the way to his sometimes tense discussions with prominent black leaders like Frederick Douglass, he made his views known but was always careful with the language he used. Lincoln would ultimately conclude that emancipation was the best course of action and that “liberal democracy can wear away even the irrationality of race.” As Guelzo nicely put it, “Democracy is the regime of reason and law, not unreason and passion, and race is no more a reasonable consideration in understanding either the natural rights that inhere in all human beings or the civil rights that define democratic laws than the color of one’s hair or the length of one’s inseam.”

The book’s epilogue explores a topic that is as impossible to be certain about as it is impossible to resist speculating about: What if Lincoln had lived? The United States would have been very different had John Wilkes Booth’s April 14, 1865, assassination attempt at Washington’s Ford’s Theatre failed. Guelzo guesses that Lincoln’s extended leadership would have considered several paths to enhance democracy, including black voting rights, black economic integration, and land ownership. How Lincoln would have dealt with the “bureaucratic miasma” that affects American democracy and all democracies, the federal judiciary’s possible intervention related to legalities involving free black people and the Emancipation Proclamation, and additional layers of resentment against his presidency is impossible to determine.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

“In a Lincolnesque future,” Guelzo prophesies, “democracy will exhibit three characteristics.” These would have been recovering consent, embracing equality to the point that “no privileged groups claim superior sanction for power,” and a “democracy of citizens, in which citizen is the highest title it can bestow.” This would have meant no slaves or masters in Lincoln’s moderately conservative vision for democracy.

What a fascinating experiment it would have been had it ever come to fruition. Maybe it still can.

Michael Taube, a columnist for four publications (Troy Media, Loonie Politics, National Post, and Epoch Times), was a speechwriter for former Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper.