“I saw a Rohmer film once,” said Gene Hackman in Arthur Penn’s classic mid-’70s neo-noir Night Moves. “It was kind of like watching paint dry.”

Funny as it is, this line is the cheapest of cheap shots — in part because Penn’s movie, starring the moody, recalcitrant Hackman as Detective Harry Moseby, is itself so thoroughly, indulgently entertaining when set beside the chaste, high-minded films of French filmmaker Eric Rohmer (1920-2010). It isn’t so much that what Hackman says is right but that it sounds right.

Over the course of his filmmaking career, Rohmer attended assiduously to the religious conundrums, ethical confusions, and, above all, amorous longings of comely, chitchatty young people. His best films are the so-called Six Moral Tales, including The Bakery Girl of Monceau (1963), La Collectionneuse (1967), and the world-famous art house sensation My Night at Maud’s (1969), starring Jean-Louis Trintignant as Jean-Louis, who, having set his cap for a proper young woman he encounters at Mass, finds his views needled by wayward nonconformist Maud (Francoise Fabian). It must be admitted that to admire Rohmer, then, requires training oneself to look at movies less as sources of diversion than edification, purification, even sanctification.

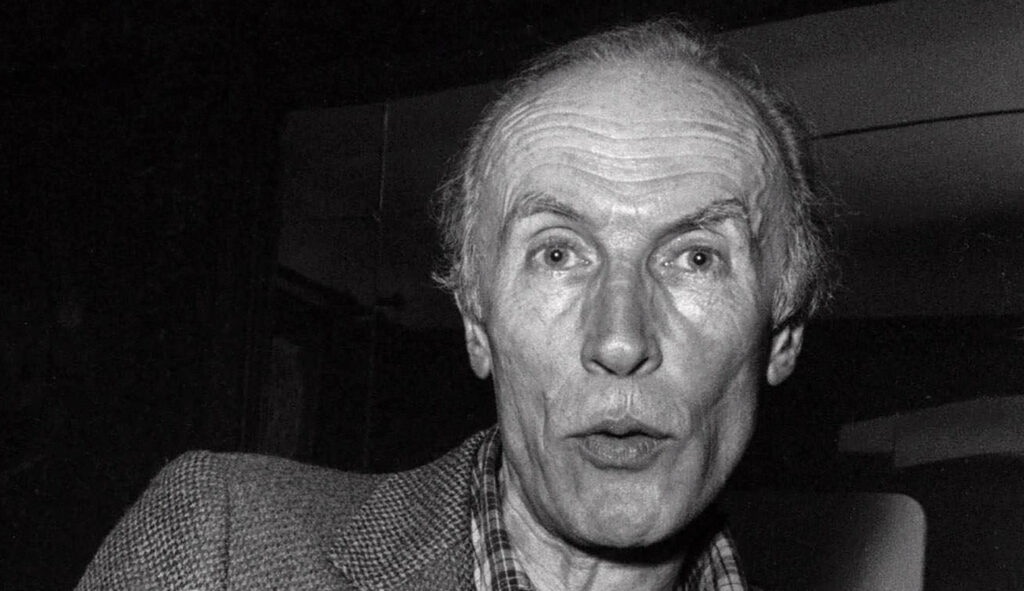

Born in Tulle, France, as Maurice Schérer, Rohmer first came to attention as a member of the fraternity of French film critics notable for their insurrectionist instincts. At Cahiers du Cinema, the journal he contributed to and later edited, Rohmer and fellow aesthetic revolutionaries Godard, Truffaut, and Chabrol waged war on the prestigious, officially sanctioned cinema of France and took up arms for the far more déclassé but infinitely more expressive films coming out of Hollywood. “No, Hitchcock is not simply a technician, but one of the most original and most profound authors in the whole history of cinema,” Rohmer wrote back then.

Yet, by the time that he made his first feature film, 1962’s The Sign of Leo, Rohmer had largely submerged his radicalism — as well as his enthusiasm for punchy, forceful directors like Hitchcock — in lieu of a style notable for its plainness and patience. Because Rohmer had sufficient respect for his characters to allow them to work through — to literally talk out — their problems, his films are profoundly unhurried. The experience of watching Rohmer’s films is certainly not like watching paint dry, but it could be described as being akin to watching the clouds roll by. And because Rohmer favored filming in real locations, often in the city streets or bucolic countryside of his native land, his films often unfolded beneath actual drifting clouds — and amid the wind, snow, or the setting sun.

These qualities are on vivid display in Rohmer’s “Tales of the Four Seasons,” a tetralogy of eros-oriented comedy dramas that play out during specific periods of the year. The four films in the cycle — A Tale of Springtime (1990), A Tale of Winter (1992), A Tale of Summer (1996), and A Tale of Autumn (1998) — have just been released on 4K UHD and Blu-ray by the Criterion Collection. The set is the ideal entry point for viewers new to Rohmer. In presenting his protagonists’ romantic odysseys in the context of the ever-changing seasons, Rohmer does not merely offer pretty backdrops but a proper context for life’s dramas: one can become terribly exercised by affairs of the heart, but the Earth will complete its orbit around the sun no matter who is sleeping with whom.

The most touching of the batch is the first, A Tale of Springtime. Anne Teyssedre stars as Jeanne, a philosophy teacher whose sober, sensible nature is seized upon by her young acquaintance Natacha (Florence Darel). Aggrieved at her divorced father for having become infatuated with a young lover, Natacha nominates her newfound pal Jeanne as a more proper companion for her parent. In its scenes of romantic scheming, the film sounds like the stuff of farce, but Rohmer maintains a moderate, even tone that allows us to see a glimpse of ourselves in Natacha’s flailing matchmaking: how often do we treat loved ones like pawns on a chessboard.

Crucially, Rohmer does not stand in judgment of calculating, confused protagonists like Natacha. Along with John Farrow, Rohmer was perhaps the most famous and most theologically serious of all Catholic directors. But in the manner of a benevolent god, he embraced his characters in the fullness of their misdeeds and mishaps, hoping that they would eventually redirect themselves to that which is good. Nowhere is this spirit of absolution more apparent than in the second film in the quartet, the majestic A Tale of Winter.

In this film, an entirely undisciplined young hairdresser named Félicie (Charlotte Véry) gets herself into a heap of trouble: she not only has an assignation with a virtual stranger but, upon parting, manages to misstate her address and thereby seemingly guarantees they will be forever lost to each other — something she realizes only after she has become pregnant by him. Yet Rohmer finds a way to redeem Félicie’s heedlessness and hedonism. After giving birth to her daughter, Félicie adopts an ascetic, self-denying lifestyle: retaining the hope that her former lover will reenter her life, she resists romantic opportunities with other men — a decision fortified when she wanders into a church and, while her daughter is distracted by the Nativity scene, says a prayer that ultimately receives an affirmative answer. That Rohmer could locate the miraculous in the quotidian contexts of a single-parent hairdresser pining for her ex reveals not only the depth of his faith but the extent of his empathy. A Tale of Winter is one of the great films of the last quarter century or so.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Rohmer accepted the world as it is, which is one reason why he eschewed the fancy photography and distracting editing popular among his New Wave peers, especially Godard. His films are not travelogues of scenic places but near-documentaries of ordinary places: a functional highway, a drably furnished flat, a weedy vineyard. Nonetheless, they attain a certain dignity through his attentive camerawork.

Less profound than Spring or Winter is A Tale of Summer, which centers on the choice of lovers available to a young musician named Gaspard (Melvil Poupaud). This minor film is nearest in spirit to, say, Richard Linklater’s Before Sunrise: a divertimento on youthful amour and not much more. Altogether statelier is the concluding A Tale of Autumn, in which a widowed winemaker, Magali (Béatrice Romand), becomes a kind of project for her friend Isabelle (Marie Riviere) and her son’s significant other Rosine (Alexia Portal), who gang up to contrive a potential spouse for the forlorn woman. When Isabelle places a personal ad intended to attract a man for Magali, she describes her friend as seeking “a man who appreciates moral and physical beauty” — in effect, Rohmer’s description of himself. Taken together, “Tales of the Four Seasons” reminds us that stories of romantic striving and scheming can make for thrilling moviegoing.

Peter Tonguette is a contributing writer to the Washington Examiner magazine.