Lawrence of Arabia: My Journey in Search of T.E. Lawrence is the first biography I’ve read in which the author explains what it’s like to kill a man: “I had often shot at people hundreds of yards away — vague shapes behind rocks who were busy firing back — but never before had I seen a man’s soul in his eyes, sensed his vitality as a fellow human, and then watched his body ripped apart at the pressure of my finger.”

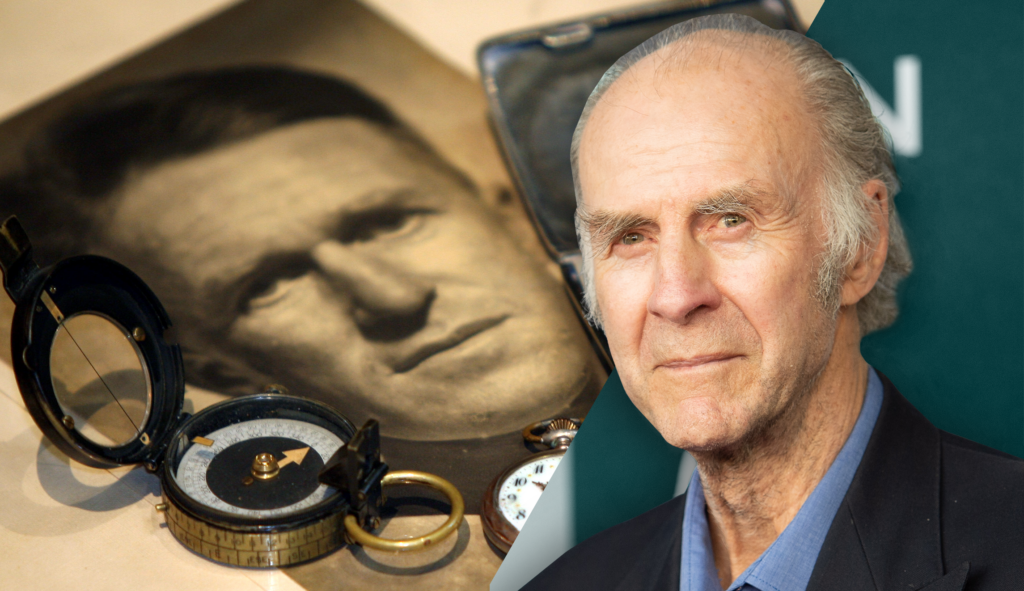

But Ranulph Fiennes is not a typical biographer. Fiennes, a distant cousin of the Hollywood actor Ralph, is something close to a household name in his native Britain, where he is frequently described as “the world’s greatest living explorer.” His exploits merit the title. Fiennes has no fingers on his left hand because, in 2000, he suffered frostbite during a failed solo attempt to walk to the North Pole. (After returning to England, he amputated the necrotic bits himself in his shed using a power saw.) In 1969, he piloted a hovercraft 4,000 miles up the Nile. From 1979-1982, he led a two-man expedition to complete the first, and to date only, surface circumnavigation of the Earth across the North and South poles. In 1993, he and a collaborator became the first men to cross Antarctica on foot, unsupported. In 2003, four months after suffering a heart attack, Fiennes ran seven marathons on seven continents in seven days.

Those feats have given Fiennes the credibility to write biographies of explorers such as Ernest Shackleton and memoirs with titles such as Living Dangerously. The conceit here, in Lawrence, is to pair a biography of the hero of the Arab Revolt with Fiennes’s military experiences leading a reconnaissance platoon during the Dhofar rebellion in southwest Oman in the late 1960s. That 12-year civil war pitted the Omani Sultanate, backed by its former British rulers, against Marxist guerillas supported by communist South Yemen.

Lawrence, who had a conflicted relationship with his enormous celebrity in his own time, is one of the rare figures of the First World War who continues to fascinate the popular imagination and garner serious historical attention. No history of the modern Middle East could plausibly be written without him.

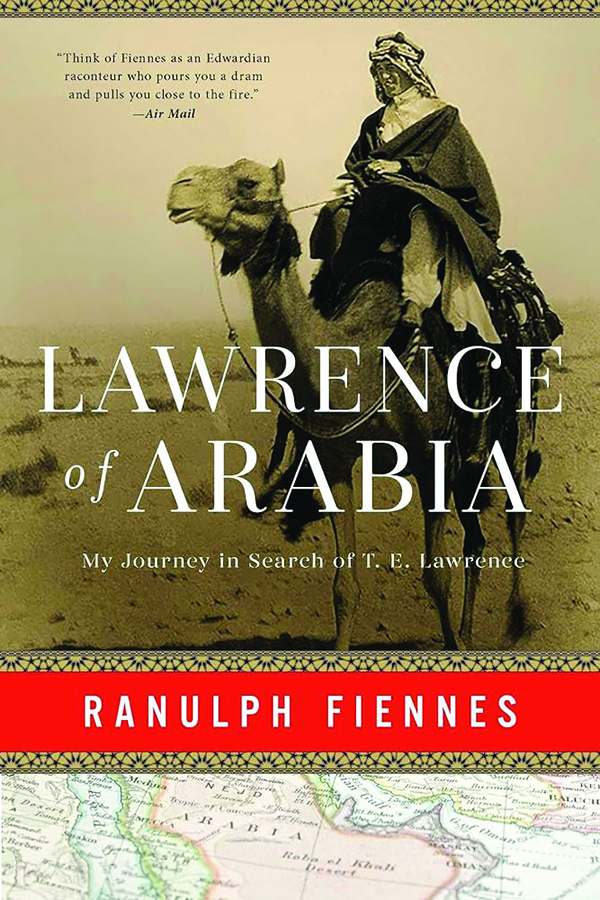

Fiennes’s new biography is a highly readable entrant among the scores of Lawrence biographies that have proliferated since his early death in a motorcycle crash in 1935 at the age of 46. Fiennes’s primary innovation is to compare the events of Lawrence’s life with his own experiences in Oman. Reflecting on how Lawrence, as an Englishman, tried to accommodate the cultural and religious sensitivities of Arab tribesmen under his command, Fiennes recounts telling one of his men about the Apollo 11 moon landing.

“The following morning, I told one of our men this momentous news. ‘What!’ he exclaimed. ‘It cannot be. The moon is a holy place known only to the Prophet. No man can go there. No aeroplane can carry enough petrol.’ I explained as best I could what a spacecraft was, and when he saw that I was definitely not joking, the man grew angry, glaring skywards. ‘The blasphemers! How dare they trespass on holy ground. I will pass the word about, and tonight we will shoot many rounds at the moon.’”

While Lawrence’s memoir Seven Pillars of Wisdom is a masterpiece, at 660 pages, it can also be tiresomely detailed. The authorized biography of Lawrence, an invaluable resource, is even more of a doorstopper at nearly 1,200 pages. Lawrence is an efficient tale, clocking in at 300 pages of generously sized font.

What Fiennes gains in readability and the personal credibility of someone who has fought deep behind enemy lines with Arab irregulars, he sometimes lacks in skepticism. As one of the characters in David Lean’s epic 1962 film Lawrence of Arabia says of Lawrence, “He was a poet, a scholar, and a mighty warrior. He was also the most shameless exhibitionist since Barnum & Bailey.” What continues to intrigue anyone who studies Lawrence is trying to separate the fact from the legend, his true beliefs from his self-deceptions, and what might have been mere embellishment from outright fabrication.

Lawrence’s repressed homosexuality and expressed masochism — after the war, he paid a man to whip him over the course of 12 years — is central to these questions about his motivations and actions. His dedication at the start of Seven Pillars, “To S.A.,” suggests that personal love was at the root of his devotion to the Arab cause. While Lawrence never confirmed the identity of “S.A.,” it is all but universally accepted as Selim Ahmed, a teenage boy Lawrence lived with at an archaeological site in northern Syria before the war and who died sometime around 1916, before the two could be reunited.

While Fiennes discusses Lawrence’s homosexuality and masochism extensively, he also accepts at face value one of the oddest episodes that Lawrence describes in Seven Pillars. Lawrence claimed that in November 1917, while on a lone reconnaissance mission in an enemy town, he was captured by the Turks, subjected to an attempted rape by the Turkish governor, stabbed, beaten, and whipped, was allowed to escape, returned to his encampment at Azraq in eastern Jordan, and then rode by camel to Aqaba nearly 200 miles away, all within the space of six days.

Fiennes gives this episode enormous weight, claiming that it might have spurred Lawrence to massacre surrendering Turkish troops later and to excuse the sack of Deraa when his troops captured the city in September 1918. “He knew this was an accepted Arab practice, while some were so scarred by their treatment by the Turks that they now barely saw them as fellow human beings,” Fiennes writes. “After his treatment in Deraa, there must also have been a part of him that was happy to see the town razed to the ground.”

The problem is that many of Lawrence’s biographers argue, persuasively, that the entire episode could not have happened. James Barr, in his 2009 book Setting the Desert on Fire: T.E. Lawrence and Britain’s Secret War in Arabia, 1916-1918, points to inconsistencies in the basic narrative and forensic analysis of Lawrence’s diary — Lawrence apparently destroyed the page covering the relevant days — that suggests that he didn’t travel to Deraa at all and instead remained in Azraq. Scott Anderson, in his 2013 history Lawrence in Arabia: War, Deceit, Imperial Folly and the Making of the Modern Middle East, agrees that the account in Seven Pillars is implausible but concludes that “there are strong indications that something happened in Deraa.”

Based on Lawrence’s private correspondence, Anderson proposes the disturbing theory “that Lawrence surrendered to his attacker’s advances in order to avoid being tortured — or at least to bring it to an end.” “If he escaped the worst of physical torture, it came at the price of a complex constellation of psychological ones,” Anderson writes.

It may be unfair of me to expect Fiennes to deal with historiographical and psychological questions like this, but his treatment of the sack of Deraa also points to some of the problems with his political and military analysis. One cannot help but wonder, for example, what the main Arab army was up to or what its accomplishments were while Lawrence seemingly led every front-line action with dozens or small hundreds of men. Likewise, Fiennes repeatedly notes that Arab tribes and villages like Deraa were possibly suspect, remained loyal to the Turks, or resisted the advance of “the Arabs.”

The fact is that the entire notion of the “Arab” Revolt was something between a misnomer and a political fiction created by Lawrence and the British in an effort to thwart French territorial claims and to justify installing Hashemite rulers in Jordan and Iraq. As Lawrence’s superiors were well aware, the “Arab Revolt” never truly materialized. The bedouins who rose out of loyalty to Sharif Hussein or under the influence of British gold were vastly outnumbered by their fellow Arabs in the towns and cities of Palestine, Jordan, and Syria who stayed loyal to the Ottomans right up until they were overtaken by the half-million strong British expeditionary force.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Fiennes is on much firmer ground in describing Lawrence’s contributions to the theory and practice of irregular warfare. He points out that it was Lawrence who first noticed that lightly armed, fast-moving cars could supplant the camel as the supreme engine of desert warfare. Even the advent of tanks and airplanes has not made that revolutionary tactical development obsolete, as seen when the Islamic State largely overran swathes of Iraq and Syria with a fleet of Toyota pickup trucks.

While not breaking any new ground in the controversies surrounding Lawrence, Fiennes’s biography is an excellent primer for those unfamiliar with the exploits of one of the great figures of the 20th century and a straight-talking refresher for anyone who doesn’t want to get bogged down in the endless minutiae of the four-year campaign to smash the Ottoman Empire.

Andrew Bernard is a correspondent for the Jewish News Syndicate.