There’s a legend, most recently propagated in a song from the musical Hamilton, that upon surrendering at Yorktown, the British army played the tune “The World Turned Upside Down,” an English bar ballad written over 100 years prior.

368 pp., $32.00

Though likely apocryphal, the story fits. The world had changed when Gen. Cornwallis laid down his sword to the Americans. In the aftermath of American independence, conceptions of sovereignty and loyalty, freedom, and nationhood became more malleable. International treaties brokered by some of America’s most revered diplomats declared thousands of square miles of North America to now belong to the new United States. Yet, on the ground, the removal of British forces left only a fledgling federal bureaucracy with only a modicum of control.

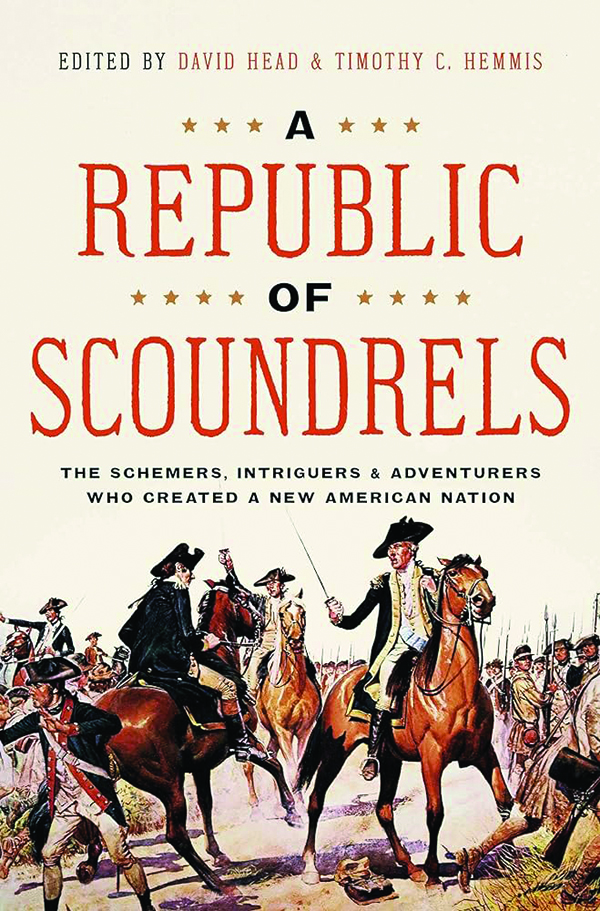

The topsy-turvy world for Americans living in a new republic, often remembered as a time when the Founding Fathers placed virtue and honor at the forefront of leadership and set the example for future generations to follow, also created opportunities for other, less scrupulous men who can be labeled as scoundrels. Edited by David Head and Timothy C. Hemmis, A Republic of Scoundrels: The Schemers, Intriguers, and Adventurers Who Created a New American Nation examines this other side of the founding generation — those in the family tree of American revolutionaries who we’d rather forget about.

Like today in places such as Eastern Europe or the Middle East, instability in government offered ample opportunity to the self-interested who were willing to take risks and bend the rules to their own benefit. As Hemmis writes in the book’s introduction, “Into the uncertain political and commercial environment stepped self-interested men who saw their chance to improve their social status, fatten their pocketbooks, and burnish their legacies.” Indeed, the 12 stand-alone essays in A Republic of Scoundrels tell fascinating stories involving betrayal, treason, murder, theft, and several other sordid aspects of building a new nation that too often gets swept under the rug of history.

Many of the “scoundrels” discussed in A Republic of Scoundrels are instantly recognizable — Benedict Arnold, Charles Lee, Aaron Burr — while others, such as James Wilkinson (who betrayed his country to Spain while serving as a territorial governor), Henry Lyon (the first person convicted under the Alien and Sedition Acts who was reelected to Congress from jail), and even the infamous murderer Jason Fairbanks, remain less known to the general public but still made a dramatic impact on the early republic. They, too, deserve attention for the roles they played in revealing and manipulating the inner workings of the culture that followed the Revolution.

Each essay demonstrates how social norms, conceptions of honor, and self-interest shaped decisions during the turn of the 19th century, and each one offers new ways to think about the founding generation. The scoundrels described in all of the essays took advantage of the situations created by living in a new, democratic nation still working to develop order out of chaos.

This was especially true in Kentucky and Arkansas, which was then considered the American West. Several essays throughout A Republic of Scoundrels describe how the regional division in the early United States revolved around the differences between the East and the West rather than the North and the South, the latter often portrayed as America’s battleground over the country’s original sin of slavery.

Hemmis’s article discussing Burr’s plot for insurrection and his trial for treason portrays this division perfectly. Anyone interested in learning more about the vice president’s descension into treachery following the killing of Alexander Hamilton would do well to start with “An American Scoundrel On Trial: Aaron Burr and His Failed Insurrection, 1805-1807.” There’s enough there for Lin-Manuel Miranda to write a sequel.

Other particularly strong essays in a book chock full of them come from James Kirby Martin writing about Benedict Arnold and Mark Edward Lender discussing Charles Lee. Both do an excellent job of humanizing two of the more notorious characters from the American Revolution. The two authors reveal the context and motivations for their subject’s actions, complicating the traditional narratives that have cast them as villains and showing, in the words of Martin, that “the Revolutionaries did not represent one big, happy family but a quarrelsome bunch.” You’ll still likely come away thinking of Arnold as American Judas, but at least his betrayal will make more sense.

Shira Lurie’s discussion of Matthew Lyons, who might be called Congress’s first rabble-rouser, and Craig Bruce Smith’s examination of the first sensational murder trial to grip the nation are also entertaining reads that will introduce readers to two “scoundrels” whom you won’t be able to help but compare to more modern counterparts.

There’s much to learn from A Republic of Scoundrels. Today, our politics have seemingly become dominated by scoundrels. From Donald Trump apparently monetizing his run for president and the scandalous emails from Hunter Biden’s laptop to a senior senator allegedly hiding gold bars like Tony Soprano while a member of the House was expelled for essentially embodying the word “scoundrel,” it can often seem without hearing the stories of history’s unvirtuous as though previous generations were inherently more moral than our own. A key strength of A Republic of Scoundrels is how it dispels nostalgia.

A Republic of Scoundrels reveals that dealing with these sorts of scoundrels is a likely side effect of living in a free, democratic society. Our culture often rewards people playing the angles, even when they’re less than honorable, after all. These essays also remind us that, in the end, it’s pain that’s worth pursuing.

Scoundrels have been with the United States since the beginning. Reading about Thomas Jefferson dealing with a traitorous vice president while multiple people tried to form new nations out of Florida and a governor profiteering from land speculation in Tennessee is oddly comforting. We’ve been here before, survived, and even prospered.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Carl Paulus is a historian from Michigan and author of The Slaveholding Crisis: The Fear of Insurrection and the Coming of the Civil War.