Among all the available definitions of cinema, few are at once truer and more politically incorrect than the one offered by Jean-Luc Godard. “The history of cinema,” the director of Breathless, Contempt, and Weekend once said, “is boys photographing girls.”

In its day, Godard’s remark undoubtedly inspired a thousand dissertations on the evils of the so-called male gaze. And in ours, it would be used as an example of the way directors objectify, exploit, or deny agency to women. No amount of woke hand-wringing, though, can fully obscure the fundamental truth of Godard’s insight. Since the earliest days of movies, directors have used the tools of cinema to present their ideal visions of femininity: D.W. Griffith was enchanted by the chaste dignity of Lillian Gish, Howard Hawks was beguiled by the salty offhandedness of Lauren Bacall, and Francois Truffaut was entranced by the ambiguous allure of Jeanne Moreau.

Talking about this should be no more controversial than discussing the women in the portraits of Pierre-Auguste Renoir or the representations of the Madonna in the masterpieces of Michelangelo, da Vinci, or Titian. That the idea of an artist of one sex offering his beau idéal of a member of the opposite sex is seen as something degrading rather than something exalting is one of the perversities of our age.

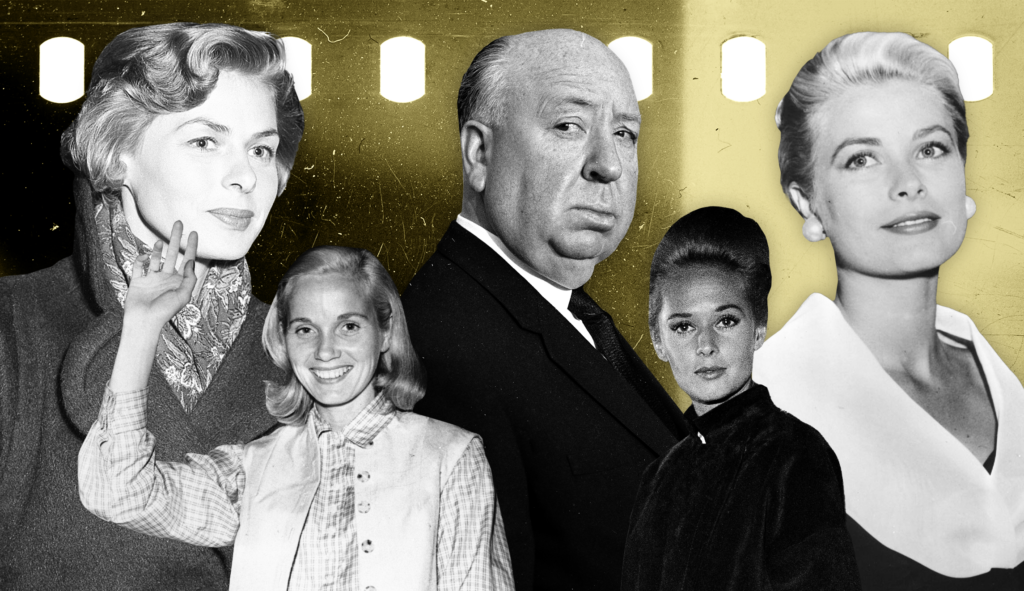

Now we come to Alfred Hitchcock, who, more consistently and obsessively than most, had a certain image of a perfect woman in mind and spent his career bringing that woman to life with a series of brilliant actresses in a series of masterly motion pictures: Ingrid Bergman in Notorious, Grace Kelly in Rear Window, Eva Marie Saint in North by Northwest, and most explosively, Tippi Hedren in The Birds and Marnie all conformed to the Hitchcock preference for icy, reserved, untouchably beautiful blondes.

To a striking, possibly unnerving degree, Hitchcock had firm, fully worked-out ideas about what the serial killer in his darkly perverse film Frenzy would have called “his type of woman.” “I feel that the English women, the Swedes, the northern Germans, and Scandinavians are a great deal more exciting than the Latin, the Italian, and the French women,” Hitchcock told Truffaut during one of their interview sessions. “An English girl, looking like a schoolteacher, is apt to get into a cab with you and, to your surprise, she’ll probably pull a man’s pants open.”

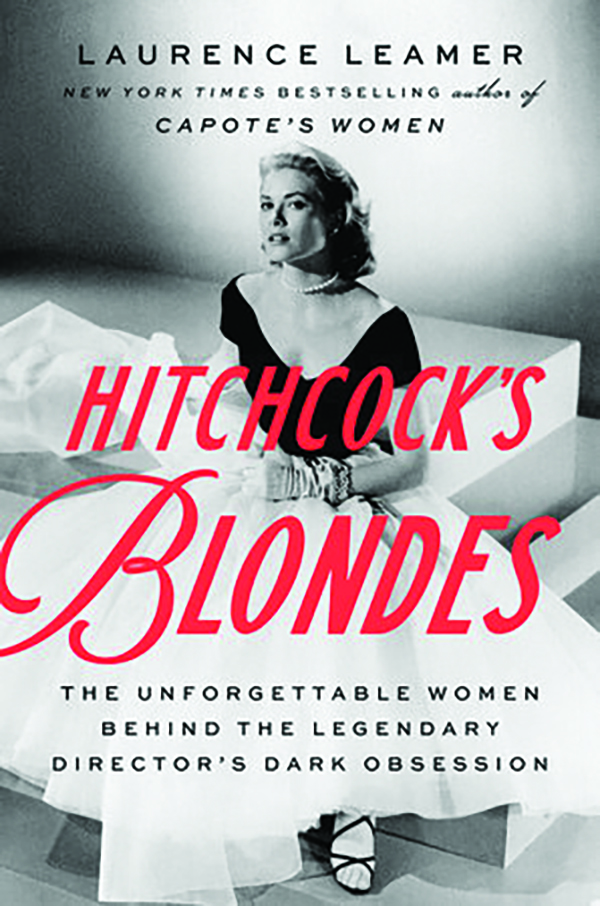

To invoke the title of another Hitchcock, the director’s rich and strange attitudes about the female of the species are reckoned with in an engaging new book about his films, Hitchcock’s Blondes. Without ever breaking entirely fresh ground in a subject so well-trod, author Laurence Leamer has the not insignificant virtue of being unafraid of the director and his baldly stated sexual obsessions and romantic preoccupations.

“To Hitchcock, blond women were the epitome of female beauty, and he fixated on them,” Leamer writes. “Blondes, to his eye, were not just some quirk of genetic nature; they were superior beings, Valkyries with coolness as pure as the Arctic snows encasing fiery inner beings that, to the right man, opened up in lusty wantonness.”

What’s more, Hitchcock was neither a simple idealizer of women (as was Griffith) nor a mere voyeur in the manner of, say, Russ Meyer. (Notably, the sole Hitchcock film that tackled voyeurism directly — Rear Window — served as a warning about the dangers of leering.) Instead, Hitchcock again and again returned to the same template: a woman of physical refinement engaged in activity that was treacherous, murderous, or otherwise ill-advised. “The director had no interest in squandering his films on saintlike women,” Leamer writes, adding, “He purified these women in his films by making them suffer until he redeemed them.”

By Leamer’s reckoning, Madeleine Carroll from The 39 Steps was the first actress to fulfill the director’s dream vision. “Hitchcock loved female beauty with unmitigated passion, and it was there before him in Carroll,” Leamer writes. “But such perfection needed to be taken down a peg.” The plot called for Carroll to be handcuffed to leading man Robert Donat, so Hitchcock made sure the two performers got used to the prop. “Hitchcock left his stars encased in handcuffs for hours, separated from everyone else on the set,” Leamer writes. This can sound awfully close to sheer perversion, but Leamer is a sensible, levelheaded writer who recognized that the director was not simply being cruel but going for an effect: “Through their adversity, Carroll and Donat bonded in ways they could never have in the stylized pattern of the set, and their attraction and mutual concern played out on the screen.”

Perhaps the actress who served longest and happiest as Hitchcock’s idée fixe was Grace Kelly, who was, in Leamer’s words, “the fully realized model of Hitchcock’s fantasy woman.” Yet because Kelly had Hitchcock’s preferred combination of qualities — cool looks and inner passion — in real life, she qualifies as a full partner in the crafting of this screen persona; her Main Line Philadelphia manners and looks notwithstanding, she had developed a reputation as a woman who freely engaged in on-set romances. She was also gamely unfazed by Hitchcock’s ribaldry, which included telling off-color jokes and reciting randy limericks. “I went to a girls’ convent school — I heard all these things when I was 13,” Kelly once told the director.

Amid all this talk of Hitchcock’s naughtiness or meanness, it’s easy to lose sight of the fact that the director did not dress up his leading ladies to humble or mortify them. To the contrary, Hitchcock’s famous attentiveness to his performers’ costuming must be seen as his way of glorifying the female form, not degrading it. Leamer recounts an episode in which Hitchcock accompanied Eva Marie Saint to Bergdorf Goodman on Fifth Avenue to help select her wardrobe for North by Northwest — a near-religious experience for the director, it seems. “The director watched with rapt interest as one model after another paraded by wearing the store’s finest,” he writes. And, in shooting the masquerade ball in To Catch a Thief, Leamer acknowledges that Hitchcock “had no higher purpose” than to show off Kelly at her most comely and elegant.

Leamer is also sure-footed in dealing with Hitchcock’s work with Hedren, whose “stunning looks” and “provocative stride” made an instant impression when he happened upon her image on a TV commercial. Hedren was cast in Hitchcock’s greatest films, The Birds and Marnie, though she later asserted that the director violated the boundaries of acceptable behavior while working with her. During one episode, she says he tried to kiss her in a limo; during another, she claims he made an “unspeakably crude” sexual proposition. Leamer is respectful of the accuser but sufficiently well-informed about the nature of the accused to be properly skeptical of the gravity of the charges. “It may be that the director’s action was not as dramatic as she, in retrospect, described it,” Leamer writes of one of the alleged incidents. “Hitchcock was a repressed man who reached out to women in impulsive bursts and then retreated just as quickly.”

Hitchcock’s wife, Alma, was the object of his unceasing love, notwithstanding his alleged bad behavior. She was not in any way a beauty of the Carroll-Kelly-Hedren type, but she demonstrated many of the qualities Hitchcock sought to bring to the screen in those women. “She showed a kind of stoic strength that Hitchcock viewed as uniquely female — the ability to carry on and display no visible signs of stress, even in trying times,” Leamer writes of Alma’s mindset following a cancer diagnosis. This is one explanation for why Hitchcock prized women of finesse and taste: they kept themselves together even when they were trekking across the top of Mount Rushmore, as Eva Marie Saint does at the end of North by Northwest.

In the end, the point is not to defend or even pass judgment on Hitchcock’s private fantasies, but to argue on behalf of those fantasies as fair game for art. If we believe the best art results from the expression of the artist’s deepest desires, Hitchcock was correct to use his freedom to express that which he longed for. If the act of boys photographing girls results in films like Rear Window, Vertigo, and Marnie, then let us commend the practice for all eternity.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Peter Tonguette is a contributing writer to the Washington Examiner magazine.