Apple TV’s Masters of the Air is better than its superb predecessor World War II historical dramas, Band of Brothers and The Pacific. Indeed, I would argue that this third outing by Steven Spielberg and Tom Hanks is one of the finest television shows ever made.

First it was the American paratroopers in Europe. Then it was the U.S. Marines in the Pacific. With Masters of the Air, based on Donald Miller’s expansive history with the same name, we witness the U.S. Army’s Eighth Air Force, 100th Bomb Group.

Based out of England, the 100th’s aircrews are tasked with getting their B-17 Flying Fortress aircraft into the heart of the Third Reich. They fly heavy and, if they survive, return home light. But as with the rest of the Eighth Air Force, their losses are also very heavy. Necessarily big budget, Masters of the Air does an excellent job at capturing the terror these young men must have felt on their many missions. Fear first comes with the call to the operations brief. The operations brief highlights the Herculean task ahead, the projector images and fact-based intelligence briefings, offering a seemingly insane juxtaposition with what the aircrews know is to come.

Then we’re up. Everyone knows that hell lurks beyond the horizon. We know that these crews will soon be stuck high above the ground in unwieldy aircraft vulnerable to the inevitable swarms of Luftwaffe fighter interceptors sent to kill them. Masters of the Air forces us to grapple with how the terror in the air carries with the men on the ground. It builds each mission, bleeding into the character and concerns of different servicemen in different ways. Every time these crews next fly, we hope they’ll be the ones that get home. But unless we have read Miller’s book, we don’t know. We care more each flight as the crews approach their 25 mission requirement to go home. But probability is no friend to these airmen.

What Masters of the Air does best is to match its telling of this tale of human courage to the moral import of that courage. The 100th’s mission, after all, is absolutely clear: to visit violence on Adolf Hitler’s empire and, as Clausewitz observed, use that “act of force to compel our enemy to do our will.”

Refreshingly, considering modern Hollywood’s general fixation with mistaking boldness for wokeness, Masters of the Air highlights the brutality of war but does not obsess over the morality of bombing Germany. Rightly so. Unlike today, the Air Force didn’t have precision-guided munitions between 1943-1945. Unlike today, the Air Force’s penetrating bombers didn’t have stealth coating. The 100th’s crews had orders and responsibilities: to drop the bombs they had so as to maximize their damage to German industry. Where population centers were hit, that targeting was not designed to kill for the sake of killing but to kill for the sake of degrading German morale and Hitler’s means of waging war. It was just.

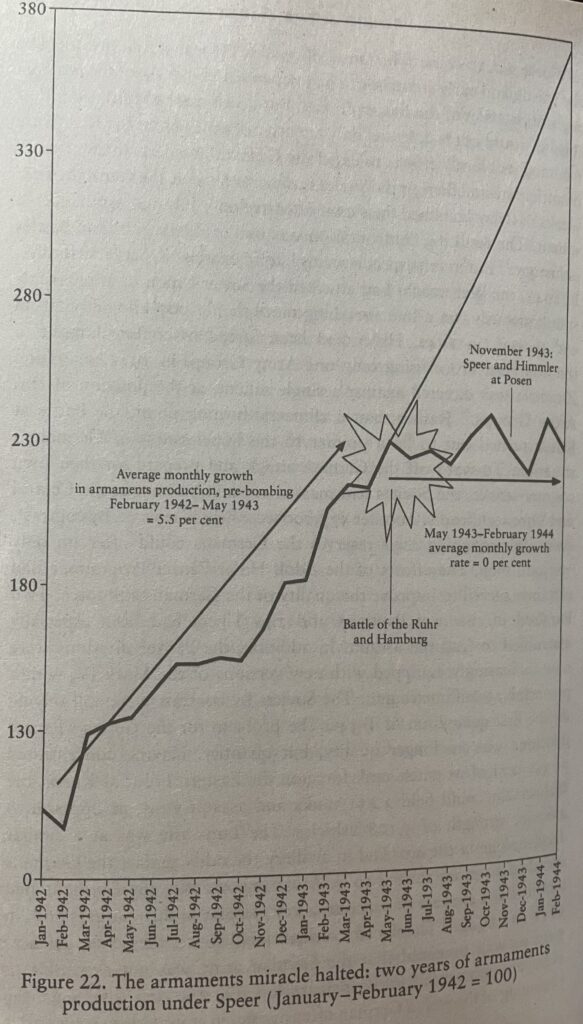

This history matters. Alongside its boost to homefront morale and allied political utility (showing Stalin that America and Britain weren’t idle alongside the Red Army’s meatgrinder experience), the military efficacy of the bombing campaign is also clear. In Adam Tooze’s excellent book, The Wages of the Destruction, he includes the chart below, which shows the dramatic impact that the U.S. and British bombing campaigns had in suspending the growth of German armaments production. Bearing this statistical history in mind, we see how Americans like those of the 100th Bomb Group made vast sacrifices to limit the weapons that could be deployed against their allies on the ground. And to end a war quicker so that civilians could be protected and liberated — and others saved from extermination.

While it includes some romance, Masters of the Air focuses on the men at war. A particular strength is its examination of leadership at various levels: aircraft, ground crew, squadron, and group. The central focus is on command pilots, Maj. John Egan and his best friend, Maj. Gale Cleve. But numerous others gain a close focus as they brave the Luftwaffe storm again and again.

Righteous attention is given to Lt Col. Robert Rosenthal. A great leader of men, the Jewish pilot won’t stop flying. He epitomizes comradeship and the responsibility of leaders to set an example to be followed. Alongside the Tuskegee Airmen who feature in one episode, we see how America’s greatest strength is diversities of origin, creed and faith made one by common purpose and patriotism.

To its great credit, the show also takes time to focus on ground crews who do everything to keep the planes airworthy and give their crews the best chance of getting home one more time. They are an integral part of the 100th. As are the English kids who look up to the “Yanks,” admiring their optimism, appreciating their gifts, and envying their incredible machines. Having one grandfather who served in the Pacific and one who flew for the Royal Air Force, including over Germany, I appreciated this warm nod to why the special relationship was and remains so special.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

The show ties these various themes together with a sustaining if sometimes subtle thread: Although their means of action are horrific, the 100th Bomb Group and its men represent something pure: the choice to serve their country, each other, and countless strangers to defeat a great evil. Superman might no longer fight for “the American way,” but these true-life flyboys did. Their service means that others can still and desire still to do the same.

Gratitude, then, should be the watchword for this show. Gratitude that they mastered the air for human freedom and a just, enduring peace.

Masters of the Air begins airing on Apple TV+ from Friday, Jan. 26