The tyranny of signifiers

Ben Sixsmith

Controversy surrounded the publication of Mark Peel’s long-awaited debut novel Shithead this year. A grueling account of a series of semifictionalized sexual encounters, running from public fellatio on the Brooklyn Bridge to a threesome with a member of the Trump administration, it sharply divided critics.

Some reviewers thought it heralded the arrival of the “neo-bro” — “the sort of man,” in the words of Emily Yudkowsky from the Startler, “who has greasy facial hair, listens to a lot of podcasts, and is just self-critical enough about his own worst instincts to imagine that he can get away with being misogynistic.” Other reviewers praised the novel, with Anna Novak in the Manhattan Review of Books calling it “the bastard son of John Updike and Hubert Selby Jr.” For Novak, reactions such as Yudkowsky’s represented a “neo-puritanism” that “would have actually got D.H. Lawrence banned.”

ELECTION SECURITY, PRIVACY, AND AI CONCERNS AMONG TOP TECH TOPICS LOOMING IN 2024

What did you think of Shithead? Nothing, really — I made it up. It’s no more real than the Startler or Manhattan Review of Books. Still, at the risk of misjudging you, I suspect that for a moment, you were forming an opinion on the controversy. Were you pro- or anti-Shithead? Tell the truth …

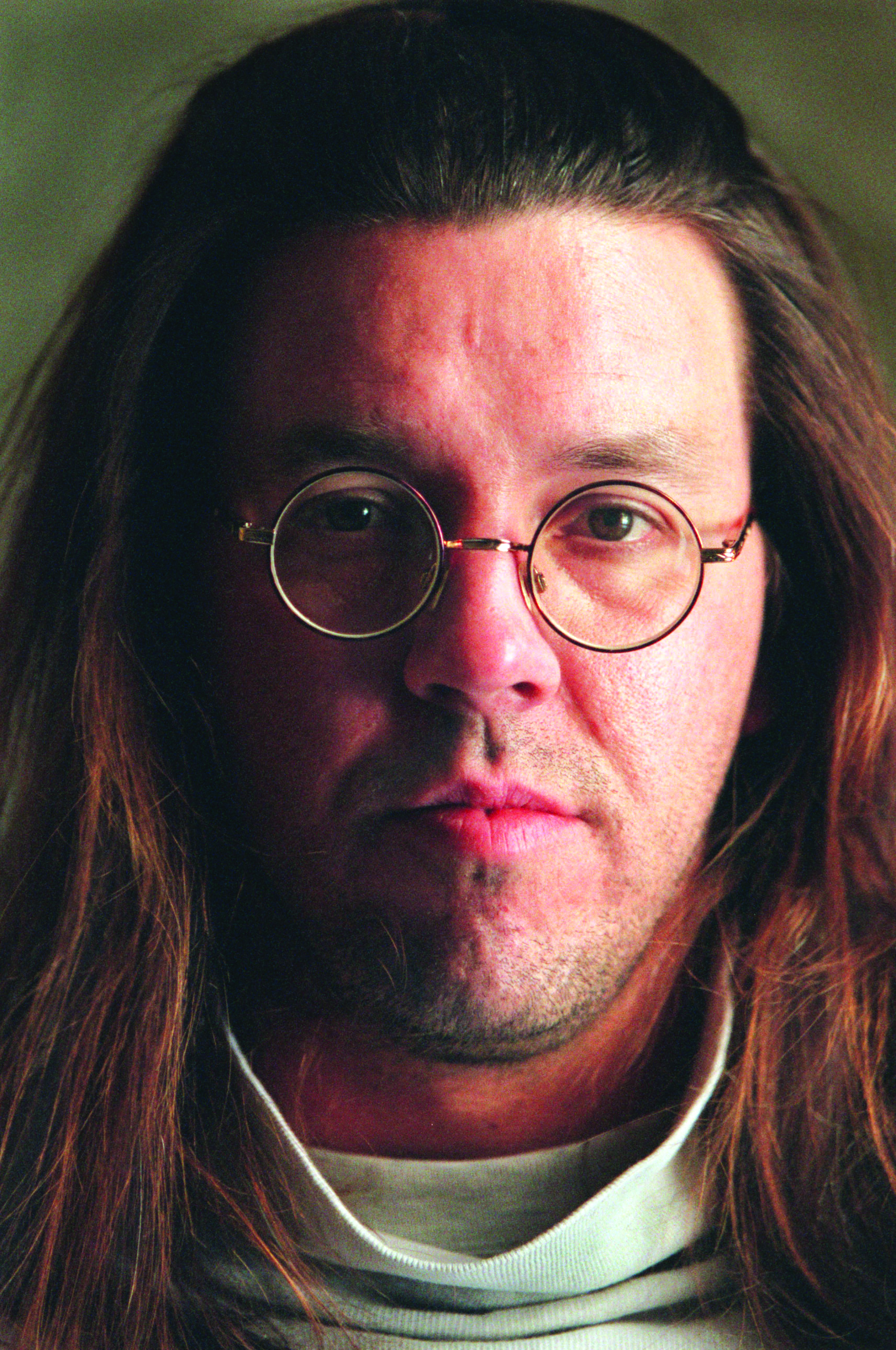

I’m trying to read David Foster Wallace’s doorstopper of a book, Infinite Jest, having never even tried. Frankly, I barely knew what the damn thing was about. Yet somehow, I knew a lot about what it culturally signifies — or, at least, what many people seem to think it culturally signifies.

To enjoy Infinite Jest, for many critics, is to be a “lit bro.” It is to like a book that “literally all white men own” (topping the list that description in the Toast comes from is Shogun by James Clavell, which I had literally never even heard of). It is to enjoy reading on public transportation. It heavily implies you’re a “pea coat-wearing liberal arts student” who has a “man bun” and enjoys telling women about how smart he is.

If people say there is a certain kind of man who heavy-handedly recommends Foster Wallace as a means of showing how smart he is, then I believe he exists. I wasn’t there and can hardly claim they are lying. Still, how common is he? How many pea coat-wearing, man bun-flaunting, David Foster Wallace-reading liberal arts students can there be in the world? Men are reading less and publishing less than women. Literary fiction is in all but terminal decline. The reign of the “lit bro,” to the extent it ever existed, has passed us by. It is no less historical than the Habsburgs.

Yet, in arguing about the accuracy of these cultural signifiers, I feel as though I’m doing the devil’s work. The real problem is the extent to which we see culture in terms of signifiers without caring about the actual content. Who cares what Foster Wallace wrote, in other words? What matters is what he represents. What matters is the kind of person he’s associated with.

I’m hardly innocent. When I think of the Irish novelist Sally Rooney, I think of angular haircuts, pronouns in bios, and handwringing conversations about the nature of privilege at little-read literary magazines. Rooney’s novels? Never read them. I know one of them is called Normal People, and the other has a rather long and flowery name, but I couldn’t tell you what either is about.

This is all quite depressing. Granted, signifiers exist and are recognizable for a reason. We need prejudices to get anything done. The world is full of networks, communities, and archetypes, not just free-floating people, and they tend to have surface-level and bone-deep commonalities.

But we seem to have little except signifiers. We have reduced books to badges. We have figured out that we can enjoy all of the gossip and status games associated with art without having to waste time on the art itself. We can have, as the cultural critic Pierre d’Alancaisez has written, a culture war without culture.

Another small example: Incessant discourse has surrounded the “Dimes Square” social scene in New York — described as a cultural hub associated, in the words of Dean Kissick, “with a certain attitude: boredom with performative outrage and disdain for overbearingly earnest didacticism.” If you’re an extremely online millennial, you probably have an opinion on the things that Dimes Square has somehow come to represent: postmodernism Catholicism, ironic prejudice, and meta-jokes. But what cultural products has it actually produced? One popular podcast, Red Scare, a play you would have had to live in New York to see, and a handful of little-read short fictions. I mean no offense to the play or the fiction (I’m quite looking forward to Honor Levy’s forthcoming My First Book, which might be a breakout star of the scene). It’s not their fault that anthropological interest in “Dimes Square” as a phenomenon has not been matched by literary or intellectual concern. But it hasn’t — because we want to argue a lot more than to read or think.

Who to hold responsible? Blaming the internet seems cheap, inasmuch as it is blamed for almost everything. (Moe in The Simpsons: “The internet! I knew it was dat. Even when it was the bears, I knew it was dat.”) Still, one can hardly overlook the fact that our ability to criticize and argue and gossip and otherwise define ourselves with or against different cultural spheres has expanded on a far greater scale than our ability to consume culture.

In a time when politics can feel acutely existential, from the politics of climate to the politics of sex, art can have significance, from our perspective, to the extent that it can serve a function. And its functionality is determined by the discourse. Put another way: The meaning of the discourse often seems to outweigh that of its subject — to the extent, indeed, that it barely seems to have one.

Ours is a time of reductive professionalization and furious competition in cultural and educational institutions. When reading becomes “consuming content,” time spent reading and thinking is time we cannot spend promoting ourselves. Think of all the hot takes I could fry up in the weeks it will take me to read Infinite Jest. Think of all the networking opportunities missed. Honestly, who has the time?

But there is no point of a contentless culture. We have to take some personal responsibility. I’ve been making slow progress through Foster Wallace’s novel, partly because I’m so aware of the act of reading it. The social (media) implications of the book have been sitting on my shoulder like a cartoon devil. What will it say about me if I like it? What will it say about me if I don’t like it? What will it say about me if I give up?

For a change, I put Foster Wallace down and read Andrey Kurkov’s Death and the Penguin, a funny, sad, and beautiful book about a Ukrainian man hired to pen the obituaries of the living. I knew nothing at all about the novel’s sociocultural connotations. It was glorious.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Ben Sixsmith is online editor at the Critic.