The story of the real places from the fictional works of Charles Dickens

Charlotte Allen

Charles Dickens had a knack for creating fictional characters, dozens and dozens of them in every book, so vivid and so individualized in personality, with wonderfully distinctive names, that it was hard for much of his huge readership to believe that these larger-than-life heroes, villains, and satiric figures to be loved, hated, or laughed at hadn’t actually existed. They were household names in Dickens’s day (1812-1870), and many remain so in our own: Ebenezer Scrooge, Tiny Tim, Sam Weller, Little Nell, Mr. Bumble, Miss Havisham, Mrs. Jellyby, Madame Defarge, Uriah Heep, Gradgrind, Fagin. The chief setting of most of the novels was London, where Dickens lived much of his life. He spent hours strolling the streets of the city looking at possible locations for his fiction, so it was to be expected that his readers would engage in elaborate detective work to do so as well.

And so they did. Dickens might be the only writer who spawned a tourist industry devoted to him and his works during his own lifetime. One of the first and most influential literary tourists was none other than Louisa May Alcott, part of an American readership for Dickens’s 15 novels that was even more avid and more demanding of detailed information about their celebrity author than its British counterpart. In 1866, four years before Dickens died from complications of a stroke at age 58, Alcott, still an unknown (Little Women didn’t appear until 1868), visited London and systematically sought out sites where either a younger Dickens himself had lived or were touted as the real-life haunts of his fictional characters.

THE OPTIMISTIC CONSERVATIVE’S GUIDE TO THE FUTURE

Alcott’s diary and an 1867 magazine article about her adventures, “A Dickens Day,” recounted imaginary encounters with some of those characters and a walk down the now-defunct Kingsgate Street in St. Giles Rookery, then perhaps West London’s most noxious slum, notorious for its narrow, filthy streets, its open sewers, its crumbling housing dating from Tudor times where entire families packed themselves into single rooms, and its booze, prostitution, disease, and crime. (It was the mise-en-scène of Hogarth’s Gin Lane.). Alcott was fearless, however (a “spinster on the rampage” she called herself), and one of her favorites among Dickens’s comic creations, the tippling, umbrella-wielding nurse-midwife Sairey Gamp in Martin Chuzzlewit, had occupied dingy lodgings above a bird-shop on Kingsgate Street whose exact premises Alcott confidently located. Alcott, insisting that Dickens must have seen and taken notes on that very building, even though she had no evidence that he did, single-handedly turned “the Gamp house” into a must-see for trans-Atlantic Dickens fans of the late 19th century.

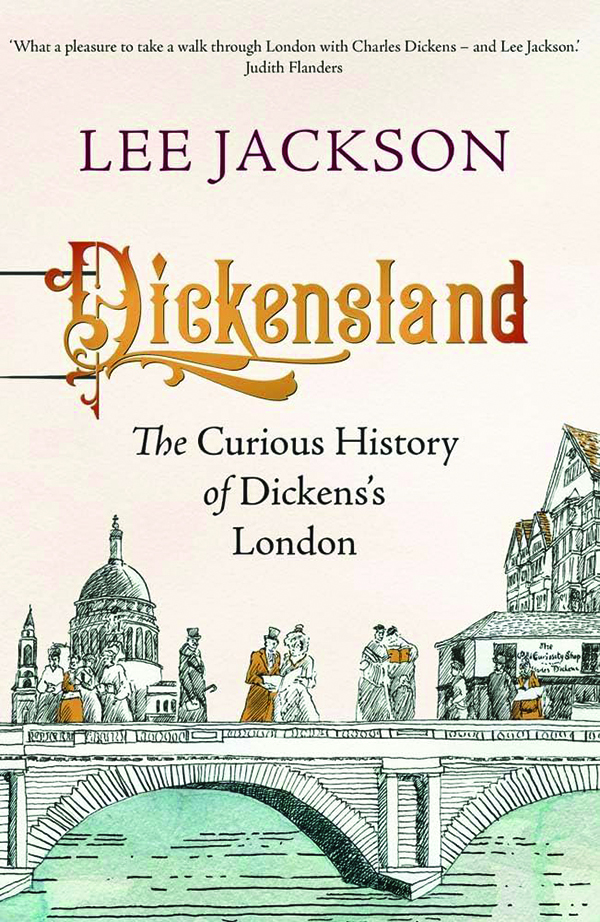

Alcott was thus a pioneer of more than a century’s worth of efforts, continuing to this day, to locate and even recreate “Dickens’s London,” the fabrication of its author, in specific places in a real-life city. This is the theme of Dickensland by Lee Jackson, author of several well-received books about Victorian London.

The problem, as Lee describes it, was that Dickens, while unerringly faithful to London geography and the atmosphere of its neighborhoods, almost never set his stories in recognizably real buildings unless they were well-known public spaces such as the Inns of Court, site of the never-ending probate case Jarndyce v. Jarndyce in 1853’s Bleak House. So identifying the possible real-life model for any particular structure described in a Dickens novel is mostly guesswork. Furthermore, Dickens, an amateur antiquarian who loved “great, rambling queer old places,” as he wrote, often set his fiction in a just-vanished past. His first novel, The Pickwick Papers in 1837, recounted incidents that had purportedly occurred a decade earlier and described a world of English stagecoach travel that had already been superseded by passenger railroads starting in 1830. That meant that by the 1870s and 1880s, when Dickens tourism took off in earnest after his death, the tidy, coach-welcoming White Hart Inn in Southwark featured in The Pickwick Papers, a rare real private structure in a Dickens novel, was a decaying, rubbish-littered wreck, its rooms turned into squalid tenements.

Most problematically of all, even during Dickens’s lifetime, and at a faster clip after his death, “Dickens’s London” — the “old” London of dark, crooked alleys and rickety Tudor half-timbers that formed the sinister background of many of his novels — was being systematically demolished in the name of slum clearance and sanitation reform. Dickens’s lifetime saw the construction of massive water, sewer, and lighting projects and broad, Parisian-style boulevards, such as Regent Street and New Oxford Street, that paved over flattened slums. The St. Giles Rookery and Kingsgate Street disappeared by the turn of the 20th century as West London went upmarket. “DICKENS’S LONDON IS VANISHING!” a newspaper headline screamed. But few Victorians actually minded much, and the very disappearance of much of the London of Dickens’s time made sussing out what was left even more exciting. “’Dickens’s London’ was now part of history, and to explore its nooks and corners was to step back in time,” Lee writes.

This means, however, that Dickens tourists, in their search for the authentically Dickensian, usually have to settle for something far less authentic, if not downright phony. The White Hart Inn was torn down in 1889, but other inns with period pretensions quickly offered themselves as replacement destinations by claiming to be inspirations for other Dickens works. The most blatant fake of all was and remains the Old Curiosity Shop. The lone Tudor edifice left standing in its Lincoln’s Inn Fields neighborhood (it is currently owned by the London School of Economics), its facade bears the Gothic-lettering inscription “Immortalized by Charles Dickens.” From shortly after Dickens’s death to the late 20th century, it was the single most popular Dickens tourist attraction in London, with female visitors, especially Americans, weeping over the villainous Quilp’s ouster of Little Nell and her improvident grandfather from their beloved shop in Dickens’s 1841 novel. In fact, the Old Curiosity Shop had nothing to do with Dickens. A previous owner had simply posted the shop’s name and inscription in 1881, and subsequent owners turned it into a Dickens-themed souvenir shop. Similarly, Dickens fans who visit the “new” London Bridge finished in 1973 may be shocked to read the “Nancy’s Steps” plaque informing them that Bill Sikes of Oliver Twist (1839) murdered his Nancy on the bridge’s 1831 predecessor. Everyone who has read the novel (or seen the musical Oliver!) knows that Bill killed Nancy inside their squalid digs.

Lee’s book is a reworking of his 2021 doctoral dissertation, and while he has gotten rid of such academic-speak verbal horrors as “heritagization” (yes, this word appears in his online abstract), the organization could be more clearly chronological. And he sometimes wanders far afield into such topics as Dickens movies and theme parks that don’t seem related to his central subject of Dickens enthusiasts’ quest to find the London of his imagination and their own in a constantly changing real-world city. Still, this is an eminently worthy project, and I’m glad he wrote this lovingly researched book.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Charlotte Allen is a Washington writer. Her articles have appeared in Quillette, the Wall Street Journal, USA Today, and the Los Angeles Times.