Mitt Romney out of time

Kyle Sammin

In 2012, an Indiana man named Eric Hartsburg got a tattoo of Mitt Romney’s campaign logo on his face. That was weird at the time. Now, more than a decade removed from Romney’s turn as the Republican nominee for president, it seems completely unthinkable. Romney bore the standard of a party whose adherents have gone from inking their faces for him to turning their backs on him with surprising speed.

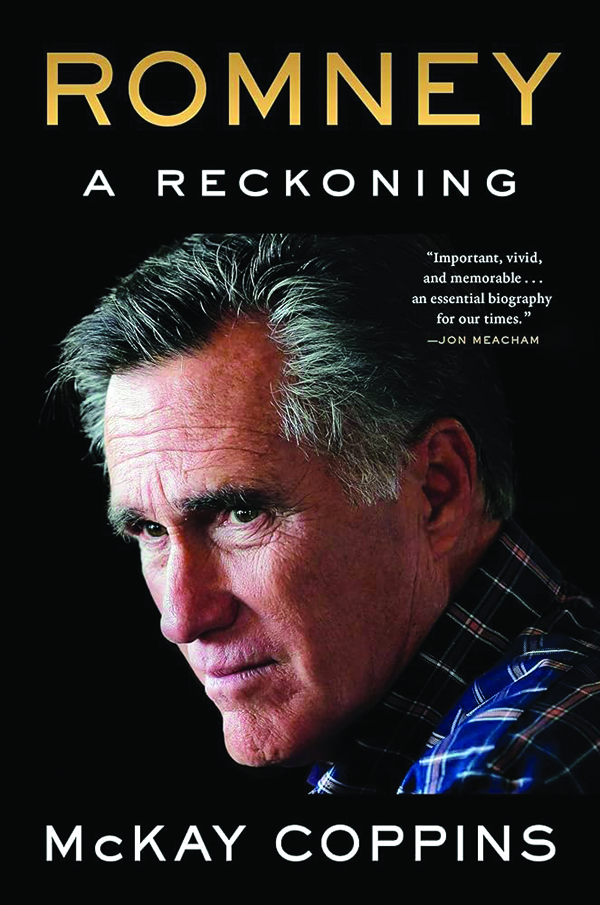

In Romney: A Reckoning, Atlantic staff writer McKay Coppins gets an inside look at former Massachusetts governor and current Utah senator, including access to Romney’s journals from those heady years on the campaign trail and interviews with the man himself. What emerges is a portrait of a man who honestly means to do good in the world without any consistent answer to what “good” means. He believes he has a special role to play, a responsibility to help the country that has been so good to him and his family. But what is meant by “help” seems mostly to mean just being the one in charge, the adult in the room, and does not necessarily include any particular set of policy prescriptions or goals.

ARIZONA SENATE RIVALS MOVE TO THE CENTER IN INDEPENDENT-MINDED SWING STATE

Throughout this book, Romney comes across as a man out of time. Part of that is simply his age — he is 76 years old, though good genes, clean living, and an obsessive focus on health have left him looking a decade younger. And part of it, too, is his earnest, religious, family-friendly personality that reminds us of the black-and-white reruns of 1950s television.

But if Romney is not a man of his time, it is also because he is a man of his father’s time. It is not surprising to learn that a man looks up to his father, especially when that father, former Gov. George Romney of Michigan, achieved success in business and in politics and earned a reputation for integrity and decency.

But so pervasive was the impact of Romney père on Romney fils that the younger man’s entire career seems to have been an attempt at a do-over for the elder’s failure to win the presidency in 1968. In doing so, Mitt finds the drive to reach great heights, higher than his father, even, but struggles to come up with an explanation of exactly why he was doing it.

Coppins illustrates all of this with well-researched, fluent prose, and much of the doubt over why Romney is running for president comes from the senator’s own words. “Why do I have no message yet,” Romney asks himself in a 2012 journal entry. It’s a fair question. He had made plenty of policy speeches, thought deeply about the issues, and had a whole party platform behind him. But if you asked, “What does Mitt Romney stand for?” even superfan Hartsburg would have struggled to say much beyond “he’s not Obama.”

There is a tendency to focus on the incumbent in any election, but Romney’s own actions did not help matters. As governor of Massachusetts, he was pro-abortion rights and helped establish a state-run healthcare system. As a presidential candidate, he was anti-abortion and anti-Obamacare. On policies big and small, Coppins writes, “Romney was no stranger to flip-flopping.”

Romney would probably find that characterization unjust. Although he changed his positions many times on many things, Coppins explains that Romney always worked hard to justify in his own mind whatever new position he was about to announce. He wasn’t lying. He was just an honest, open-minded man with a talent for rationalizing the unpalatable. And it worked, until it didn’t.

Romney’s personal uprightness and political sail-trimming are contrasted throughout the book with his successor as GOP presidential nominee, Donald Trump. They are both the sons of successful fathers who spent years in the business world before turning to politics, but that is as far as the similarities go. No matter which version of Romney you’re comparing him to, Trump is the polar opposite.

Where Romney is deliberate, Trump is mercurial. Where Romney gathers facts and studies like the professional investor he once was, Trump goes with his gut. Where Romney is obsessed with not being brought down by a blunder like the one that doomed his father’s presidential campaign, Trump says whatever he’s thinking and somehow wins anyway. Romney, with an assist from a media deeply in love with Obama, manages to come off as the candidate of the status quo, even though his opponent had held the presidency for four years. Trump captures Obama’s energy: change, above all.

Romney’s campaign was about being serious, capable, and thorough. The adult in the room, the trusted elder statesman. Trump’s was about fanatical devotion. No one would be surprised to see a Trump tattoo.

The contrast wears on Romney and causes him to second-guess himself — again, something Trump does not seem to do. What could he have done differently? What compromises should he have made? Which shouldn’t he have made?

This is not to say he is a tortured man. The Romney that Coppins presents is one who is content with his family, his wealth, and his soul. But it is also the picture of a man who wonders where it went wrong. Romney did everything “right” and lost. Trump did everything “wrong” and won. Even the “strange new respect” he won from the legacy media after 2016 leaves him cold: Where were these people in 2012, when it mattered?

And so, he entered the final act of his public life: the senator who would finally stop hedging and shifting and would simply tell it like he sees it.

Once he arrives in the Senate, though, Romney finds he is still a man out of time and, increasingly, a man without a party. Republican colleagues, he said, would whisper support for his principled opposition but decline to join in it themselves. Democrats mostly played the same game, working with him only for the pretense of bipartisanship. His closest relationship came to be, somewhat unexpectedly, with Democrat-turned-independent Sen. Kyrsten Sinema (I-AZ), herself a sui generis figure at odds with her party’s hierarchy.

Romney considered some sort of independent presidential bid on several occasions since 2012 but passed on the idea, believing it would only help Trump win. But as 2024 looks to be a warmed-over rematch of 2020, some closet centrists in both parties are sure to sound Romney out on the prospect again.

The idea is beyond quixotic. Romney has burned too many bridges in this book ever to be seen as anyone’s consensus candidate. But the concept is appealing: a wise elder statesman, keen of mind, serious in temperament, experienced at getting things done — it sounds like what many disappointed voters crave. But more than that, it sounds like an echo of the idealized past, nostalgia for a time of widespread consensus on major policy, when serious men led a serious country.

For better or worse, that time — Romney’s time — has passed.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Kyle Sammin is editor-at-large at Broad + Liberty.