Child stars provide movies with something irreplaceable and have something irreplaceable robbed from them

Peter Tonguette

“Even when we were kids, the term ‘child actor’ was shorthand for ‘future f—ed up adult,’” wrote actor Clint Howard, the rare child star to become a fully functioning adult, in his memoir The Boys, written with his brother, the equally productive director Ron. “Then as now, Hollywood is littered with cautionary tales.” The Howard siblings notwithstanding, a cursory glance at the history of show business reveals countless performers who charmed audiences as youths, fell into irrelevance as young adults, and drifted into disrepute, scandal, or otherwise sad outcomes.

Judy Garland was subjected to a prescription drug regimen at the behest of her avaricious studio employers that resulted in addictions that led to her death. Her sometime co-star, Mickey Rooney, transitioned from youthful verve to doddering crankiness as he lived long enough to become a spokesman for elder abuse. Corey Haim traded stardom for substance abuse on his way to a premature burial; the other Corey, the irrepressibly talented Feldman, has transitioned to a music career that suggests someone whose frame of reference begins and ends with 1988-era Michael Jackson. Jonathan Brandis killed himself; Dustin Diamond, “Screech” on Saved by the Bell, went bankrupt, was arrested, and went on Celebrity Fit Club before he died young.

SEPARATING THE ART FROM THE IDEOLOGIST IN KILLERS OF THE FLOWER MOON

When Shirley Temple chose Child Star as the title of her autobiography, then, it was undoubtedly with a sense of irony. Yes, during the Great Depression, her movies alleviated a nation of its troubles, and even as her fan base faded and finally evaporated, her post-stardom life was one of achievement. She powered past a failed first marriage to enjoy a stable home life and a rewarding diplomatic career, including ambassadorships to Ghana and Czechoslovakia. Even so, Temple had to have known that the loaded words she picked for her book title seldom bespoke a good, successful, or even tolerable life.

Sometimes child stars become grown-up criminals. For a time, Robert Blake seemed to be one of the exceptions to the rule for having parlayed his appearances in the Our Gang comedy shorts into tough, unsettling performances in terrific films like In Cold Blood, Busting, and Lost Highway. But he became all too representative of his type when he found himself fighting a murder rap late in life — in cold blood, indeed. (Blake was found not guilty of criminal charges, deemed liable in civil proceedings, and, for his sins, was subjected to a laughably intense appearance with Piers Morgan.)

Even those child stars who do not so brazenly crash and burn in the manner of Blake become the victims of an even worse fate: pity. Charlie Chaplin directed the astonishingly expressive 6-year-old Jackie Coogan in his masterpiece The Kid. But, upon seeing an overweight, senescent Coogan at the Oscars in 1972, Chaplin exclaimed, “He was a tiny little boy … and now he’s an old fat man.”

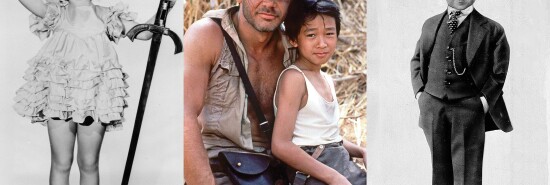

I thought of Chaplin’s remark about Coogan during this past year’s Oscars, when Ke Huy Quan, best known as Indiana Jones’s intensely verbal 12-year-old sidekick, “Short Round,” in Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, was gifted with an Oscar for his performance in Everything Everywhere All At Once. I say “gifted” because Quan’s award seemed more like an act of compassion than a recognition of achievement. His career had already peaked when he was 13. Even Pauline Kael singled him out in her review of the Indiana Jones movie: “This grasshopper-size kid is smarter and more resourceful than Indy, and a good case could be made for his being the true (and invulnerable) hero of the adventure.” Within a few years, though, he was essentially forgotten. And in this, he was not unique.

The sad truth is that Quan, while every bit as talented as Kael said he was, is one of countless former child stars whose undeniable showmanship does not necessarily foretell acting chops as adults. For this reason, so many of the best child stars — including, after a time, Shirley Temple — slipped into other occupations once they became taxpayers. Have you seen Peter Ostrum from Willy Wonka or Thelonious Bernard from A Little Romance in anything lately? No, because both seem to have realized that, after giving two of the best child performances in history, it was best to call it a career. The Oscar given to Quan attempted to undo this natural state of affairs.

We must acknowledge that we pay attention to young actors not because they are adult thespians in the making but because, at their best, they are offering things that trained actors often struggle with — things like authenticity, believability, and instinctiveness. What they do cannot even be characterized as acting as Stella Adler would have understood it. This is not as grim as it sounds. In fact, the limited toolbox of child actors is an asset, not a liability. Even if they have received coaching, child actors obviously have less access to the techniques (and tricks) of trained troupers and therefore tap their own inner resources.

When Jackie Cooper displays anguish over the fate of his decrepit boxer father in King Vidor’s classic The Champ, we have the sense that we are not watching canned acting as much as an expression of pure, even volcanic, emotion. “When a child without acting experience is on set — and this is not meant in any kind of derogatory way — he brings a presence like an animal, a cat,” Jean-Pierre Dardenne, who co-directed The Kid with a Bike, told the New York Times in 2012. “He is there.”

In one of the most famous scenes in his masterpiece The Bells of St. Mary’s, director Leo McCarey assembled a group of children to play parochial school students pulling together a Christmas pageant. The children tell the story of the Nativity imperfectly, in fits and starts and with something less than Biblical accuracy, just as McCarey intended. “I just turned them loose,” McCarey said. The great child stars give audiences access to a child’s imagination.

In the movie To Kill a Mockingbird, Mary Badham as Scout and Phillip Alford as Jem actually inhabit the outlook of childhood. Under the superbly tactful direction of Robert Mulligan, Badham seems to know firsthand the joy of roaming unsupervised on summer days, the fear of the creeping adult world, the confidence placed in a father. And the same must be said for the other on-screen landmarks of child stardom: Roddy McDowall in How Green Was My Valley, Henry Thomas, Drew Barrymore, and Robert MacNaughton in E.T., Sara Walker and Andrea Burchill in Housekeeping, and, most startlingly, Victoire Thivisol in Ponette, who as a 4-year-old girl was asked to play a child in mourning over the loss of her mother — and did so with painful plainness.

In the end, the example of the washed-up, ruined, or, sadly, deceased child stars among us offers a compelling argument against any parent ever signing up a child to star in a movie. And trying to transform a child star into an adult actor is equally foolhardy, too often resulting in the tragedy of Judy Garland, the insanity of Robert Blake, the — sorry to say it — pitifulness of Ke Huy Quan. Yet, every so often, a child turns up in a movie or show and cuts through the phoniness and self-consciousness of the adults around them. And the movies are better for it, even if the children are not.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Peter Tonguette is a contributing writer to the Washington Examiner magazine.