Gay Talese’s fanfare for the common man

Peter Tonguette

Gay Talese wears a fedora. He also wears a three-piece suit, a pocket square, and very often a rather grand scarf. Sometimes, it seems as though he is the last man in America to dress this way, but that is because he is the last journalist in America to write the way he does.

These two facts about Talese, his taste in clothes and his way with words, are not coincidental. For Talese, writing well and dressing well are inextricably linked. “I would always dress as if I was on some very important business,” he once said in an interview. “I dressed up for a story. I thought the story is important business.”

NEWSOM DEFENDS FAILURE TO ADDRESS HUMAN RIGHTS ABUSES WITH CHINA’S XI JINPING

First as a daily newspaperman, then as a magazine features writer and founder of New Journalism, and finally as the author of fat tomes that routinely became cultural sensations, including The Kingdom and the Power (1969) and Thy Neighbor’s Wife (1981), Talese brought a seriousness of purpose to his trade. He was guided by the conviction that the marginal, tangential, and incidental figures in society were as or more interesting than the bigwigs and institutions they served. And that they revealed as much or more about those bigwigs and institutions. That he dressed up to interview them was one way of expressing that conviction. Wearing a coat and tie while chasing down Frank Sinatra’s employees and hangers-on, as he did while reporting his classic piece for Esquire, “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold,” was one way of saying that employees and hangers-on were worth talking to.

Talese, a native of Ocean City, New Jersey, who turned 91 earlier this year, has just released a book in which he takes a victory lap for his approach to reportage. Because he’s still the most stylish writer out there, and still the most exceptional in his choice of subjects and sources, he’s earned that right, but those who read closely will find not just a guidebook to best practices in journalism, New or otherwise, but something of a holy text.

“I may not get the piece we’d hoped for — the Real Frank Sinatra — but perhaps, by not getting it, and by getting rejected constantly and by seeing his flunkies protecting his flanks, we will be getting close to the truth about the man,” Talese wrote in a 1965 letter to Esquire editor Harold Hayes, as he was toiling on the Sinatra piece and coming to accept that his face time with Sinatra was going to be highly limited.

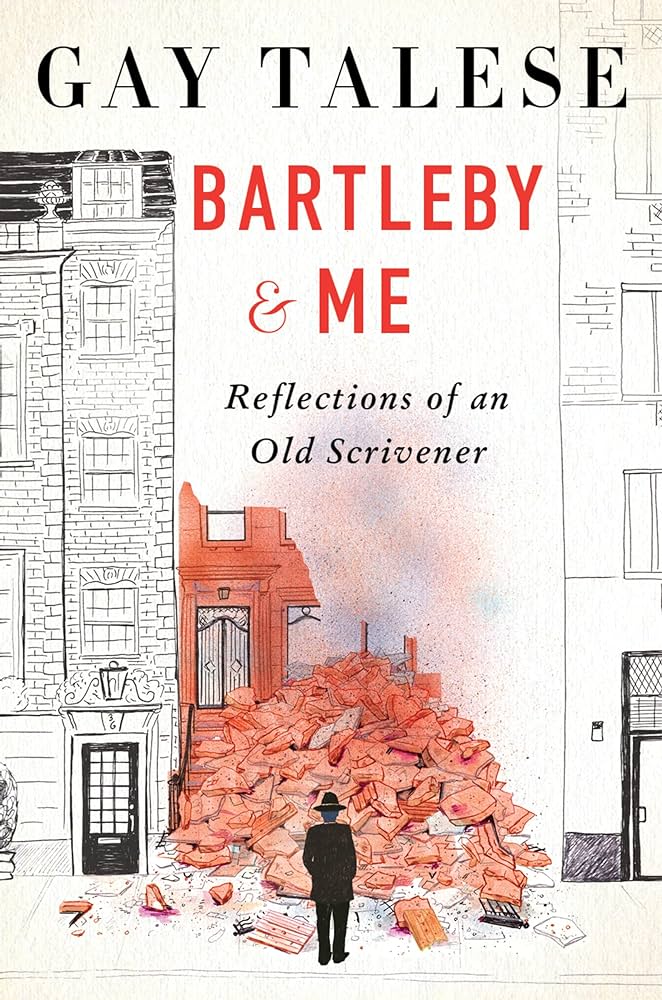

Talese may have sounded an equivocal tone to Hayes, who had expected a conventional profile of Sinatra. But in truth, the writer had been certain of his intentions since he first was hired by the New York Times in the mid-1950s. “As a reader, I was always drawn to fiction writers who could make ordinary people seem extraordinary,” Talese writes, pointing to the namesake of this book: Herman Melville’s “Bartleby, the Scrivener.” “I have met many people who, in one way or another, reminded me of Bartleby,” Talese writes. “These are people whom I might see regularly but whose private lives remain private.” He cites doormen, waiters, cleaning women, and those who work at hardware stores, dry cleaners, or “other places employing people who might meet an obituary editor’s definition of a nobody.”

Much of the book is taken up with Talese’s attempts to persuade assorted editors that these alleged nobodies are worthy of expending ink. “For the drama editor, I wrote about a stage-lighting technician on Broadway,” he writes of his stint at the New York Times. “For the national news editor, after the Russians in 1957 had launched a dog named Laika into orbit, I wrote about other headline-making dogs in history.” The Sinatra piece was, in fact, the result of a kind of compromise: Talese accepted the assignment as a goodwill gesture since Hayes had agreed to the writer’s larger project of interviewing employees at the New York Times who were consequential but not recognizable, including obituary writer Alden Whitman. In the present volume, Talese spends multiple chapters on the particulars of Whitman’s youth, personal life, and the professional path that took him to the New York Times and eventually to the obituary desk, all of which is sufficiently fascinating to vindicate his career-long hunch: that the life of virtually anybody can be compelling if thoroughly reported and elegantly told.

Although Talese summarizing his greatest hits from more than half a century as a celebrated writer can have the flavor of a valedictory, he more often than not shows rather than tells. His account of writing the Sinatra piece ends up being as compelling as the Sinatra piece itself: His negotiations with Sinatra’s publicist, his observations of Sinatra’s double, his discussions with Sinatra’s daughter, and so much more along these lines are recounted to help explain the provenance of the piece but also do the work of justifying the piece itself and Talese’s overall approach. These people really do give us a flavor of what the great man was like, how insulated he was, how overworked he was, and finally, how fragile any great talent is. After all, he keeps insisting he has, or is just getting over, a cold.

Along the way, Talese dispenses advice that writers today should gobble up. Allergic to tape recorders, Talese advises stocking up on “shirt folder board,” the sort that comes back with the laundry, and cutting it into dimensions that might be stuffed into a jacket pocket for easy note-taking. It goes without saying that such notes are taken in person. Phone interviews? Forget about it: “It prevents your learning a great deal from observing a person’s face and manner, to say nothing of the surrounding ambiance.” It’s also harder for a possible interview subject to say no in person, he adds.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

What keeps Talese from sounding self-serving is his frank admission that persuading publishers and subjects to go along with his sort of journalism has not gotten any easier. Talese recounts several failed literary projects from recent years, including a book about kitchen workers in a New York restaurant and a book about the backstage employees of the Metropolitan Opera. For various reasons, both tantalizing projects and several others failed to materialize, although packed into the final third of the present volume is a kind of Talese book in miniature: a freshly written account of Dr. Nicholas Bartha, a New York physician who, facing the imminent loss of his cherished brownstone in what seems to have been an unjust decision in a divorce case, elected to blow up his home and, in the process, take his own life. As ever, Talese is attentive to the ambitions, psychology, and demons of a man who lacked fame in the conventional sense but nonetheless had a consequential life and astonishing death.

In an age in which fame is often the lone determinant of media coverage, Talese offers a shining counterexample. You’ll come away from his last book believing there are no nobodies, there are just bad writers.

Peter Tonguette is a contributing writer to the Washington Examiner magazine.