The collectible watch market knows the falling price of everything and the value of nothing

Jack Baruth

There have been expensive wristwatches for as long as there have been wristwatches of any kind, but it took the arrival of the smartphone and various other digital assistants to light a fire under the “luxury timepiece” business. There’s some justification for it, actually. After a brief and embarrassing period of Apple Watch mania, we all now understand that this much-coveted supercomputer-on-the-wrist is simply a closer and more humiliating leash to one’s employer, a public declaration of fealty to the imperious demands of email and Slack messages that can vibrate one’s pulse point instead of one’s pocket tackle.

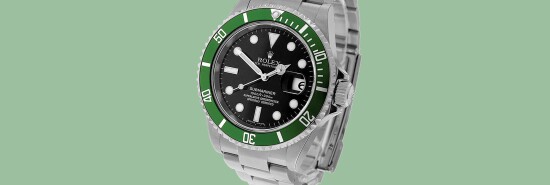

By contrast, wearing a Rolex Submariner or Omega Speedmaster in 2023 is an explicit statement of wealth and (admittedly minor) freedom. It’s also jewelry that even the most rigorously Puritan fellow on the East Coast can wear without blushing. The best Swiss watches sit lightly on the wrist and offer a sapphire-glass back window on their micrometer-precise and strangely mesmerizing operation. Wearing a Patek Philippe or Vacheron Constantin puts you in the same rarefied air as men who drive Ferraris and Bentleys to work, with the additional benefit that you won’t need to leave it at the mercy of some Cro-Magnon garage 50 feet beneath Park Avenue.

APPLE TO MAKE TOOLS AND PARTS REQUIRED FOR ‘RIGHT TO REPAIR’ AVAILABLE NATIONWIDE

For these and many other reasons, the secondhand prices of luxury watches have been on the upswing for some time now. COVID-19 turned the chart of that mild rise to one that resembles a hockey stick. Faced with the prospect of their own mortality and a lot of newly liberated travel budgets, executives and professionals everywhere started pestering their authorized dealers, or ADs, for their dream watches. Rolexes that sold for $6,000 new were changing hands for $25,000 and up — if you could find someone willing to sell. This, in turn, made the $50,000 pieces from the “holy trinity” of Patek, Vacheron, and Audemars Piguet seem more attainable, promptly sending their values into six figures.

(Fun fact: The rapper Future once famously declared, regarding his lady friends, that he rewards them with Audemars Piguet Royal Oaks. “If she ain’t got no AP, she is not mine! She belongs to the streets!” Knockoff Royal Oaks, which can be had from Chinese sellers for under $500, are known to the cognoscenti, who delight in spotting them on celebrity wrists, as “Fraudemars.”)

The market proved able to support inanities like watch-rental schemes — just $1,000 a month or more to borrow and wear someone else’s Rolex — and investment vehicles that held Pateks instead of preferred shares. It was a party with no end, a rising tide that lifted even the leakiest of boats from third-rate brands such as Tag Heuer and Ulysse Nardin … until it wasn’t.

As with so many varied and diverse cultural phenomena of the past three years, we can now expect most of the “watch guys” either to minimize or deny their involvement with timepiece speculation in the years to come … perhaps up to three times before the Blancpain Villeret Réveil GMT on their wrist strikes its elaborate mechanical chime tomorrow morning. Let’s hope that said Blancpain’s chime actually works come sunup, because the cost of replacing the delicate and microscopic mechanism is perilously close to the whole thing’s current retail value of about $15,000, down from a $55,000 introductory price in 2014 and subject to a few wildly speculative swings since then.

Morgan Stanley, which tracks prices of “investment-grade” watches from Rolex and other brands, announced in an October research report that prices in the secondhand market have dropped as much as 20% year over year. That puts prices back where they were at the beginning of 2021, but nobody thinks this will be the end of the bloodletting. Another year like this, and used luxury watches will sell for their approximate MSRP new. This may even apply to graduates of the new and highly touted “certified pre-owned” program from Rolex, which apes similar (and successful) efforts by Lexus, Audi, and other automakers to maintain both a market for their older products and create a second profit stream for authorized dealers.

Perhaps some of the strongest remaining secondhand values out there in wristland belong to a series of cheap plastic Swatches that ape the branding and aesthetic of $10,000-and-up watches from other brands in the Swatch group. These battery-powered “MoonSwatches,” which imitate the stainless-steel, mechanically driven Omega Speedmaster, sell for $260 each in a very limited number of stores but often change hands for a thousand dollars or more. Strangely enough, the values of the “real” watches on which the Swatches are based have also stayed robust, perhaps because it is a truly subtle delight to wear a Speedmaster in a room full of MoonSwatches.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

This market downturn is all bad news for the majority of Swiss watchmakers, who have worked mightily to increase both overall production and the list price of their products. Retail inventory is remarkably high across the board, and customer interest is declining rapidly. Expect it to decline further as various well-heeled nouveau customers discover the undocumented drawbacks to owning complex Swiss watches, such as thousand-dollar services every few years and the omnipresent possibilities of theft, damage, or simply mechanical failure. If the (appropriately named) “complication” in a high-end watch grinds to a halt, the cost can be quite similar to replacing the engine in a brand-new Mercedes — minus the part where Mercedes covers it via warranty, of course.

Don’t let any of the above dissuade you from adding a proper mechanical watch to your life. There is some genuine joy to be had in them, and they offer a lovely escape from the ephemeral and digital world around us. A Rolex or Omega has real heft, it is assembled by human hands yet with almost inhuman perfection, and it will never, ever beep at you in the service of your employer. As with any other bubble, some “investors” will be left more whole than others. It’s hard to imagine that an authenticated Rolex will ever be worthless in the secondary market. There is an unstoppable global demand for such an item, and in any event, if you can’t sell it, you will still have the pleasure of owning a truly impressive machine. There should be some real bargains in the years to come for the people who can enjoy and appreciate them without worrying about resale value or investment potential. On the other hand, everyone who thinks they can wear an investment portfolio on their wrists should tilt those wrists and take a good look. According to my watch, it’s probably time to sell.

Jack Baruth was born in Brooklyn, New York, and lives in Ohio. He is a pro-am race car driver and a former columnist for Road and Track and Hagerty magazines who writes the Avoidable Contact Forever newsletter.