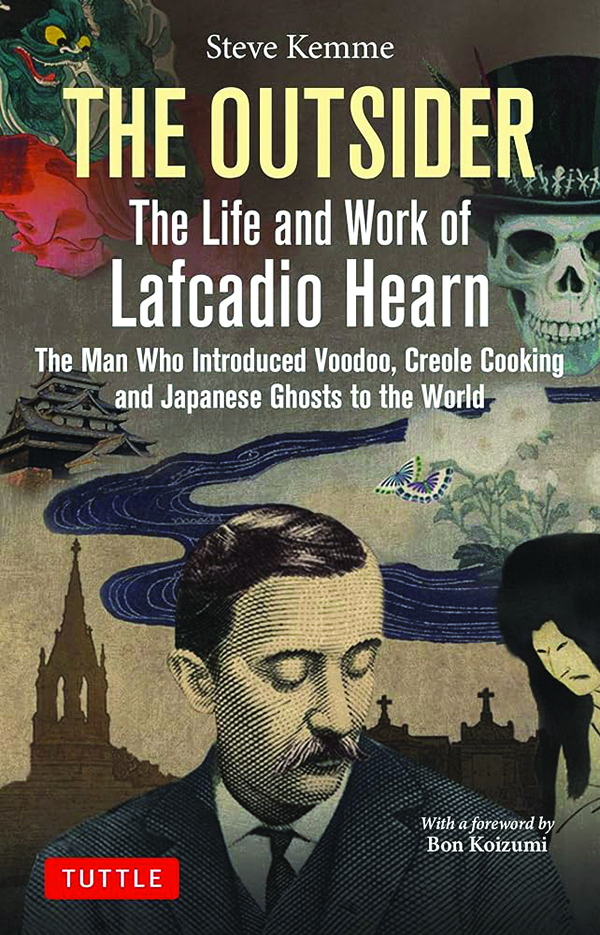

A new book follows Lafcadio Hearn, the historical travel writer who fused the world

Diane Scharper

During the Meiji period (1868–1912), Japan opened its doors to the world. Under “sakoku” from 1639-1853, the archipelago nation had isolated itself. But now, novelists, poets, and artists from inside and outside exchanged ideas and experimented with new forms. Innovation altered the scope of Western aesthetics and brought about the shift to modernism, captivating audiences from West and East.

Patrick Lafcadio Hearn was one of those who first became enthralled with everything Japanese, as Steve Kemme explains in his informative though somewhat dry biography, The Outsider. Hearn covered the 1884-85 New Orleans World’s Fair for Harper’s Weekly, and he was especially hooked by the Japanese exhibit. Hearn read Percival Lowell’s book, The Soul of the Far East, a popular late-19th-century study of Japan, and loved it. In a letter to a friend, he called it “a marvelous book — a book of books — a colossal, splendid godlike book.” As Kemme describes it, each stage of Hearn’s life seemed to be a preparation for the next, and for his eventual glory days in Japan.

THE REISSUE OF GREAT SPY NOVELIST LEN DEIGHTON’S WORK IS AN OCCASION FOR ANOTHER LOOK

Everything conspired to make Hearn an outsider. Born on the far-away Greek island of Lefkada, Hearn lost contact with his mother after his parents’ marriage was annulled. Hearn spent his growing-up years living with his Catholic great aunt in Ireland where he was inspired by Irish myths and the Irish penchant for storytelling. His aunt provided him with a comfortable life until she lost all her money. She also pushed her Christian beliefs on Hearn. He came to detest Christian theology, rituals, and saints and was intrigued when he learned about the spiritual aspects of Japanese Shintoism and Buddhism, the beliefs of which adhered more closely to those in his own mind. Partly because his only connection to his mother was a religious icon she had given him, he was fascinated by anything supernatural, believing in ancestor worship and reincarnation.

He resented his Irish father, who left his mother to marry and start a family with a former sweetheart. Hearn believed that everything good in him stemmed from his mother’s “dark-race soul.” This, as he explained in a letter, included “my admiration for what is beautiful or true … my sensitiveness to artistic things which gives me whatever little success I have — even that language power … came from Her.”

Hearn went to Cincinnati at 19 and in a few years became a celebrated crime reporter despite not finishing high school. He probed the seedy side of the city and wrote for several publications including the Cincinnati Daily Enquirer, where he made his reputation writing about the Tan Yard murder in the overwrought style of Edgar Allan Poe.

His first marriage to a mixed-race woman in Cincinnati at a time when miscegenation was called a crime caused him to be fired from his job. But he was soon hired by the Cincinnati Commercial. When he moved to New Orleans and later to Martinique, he indulged his taste for the exotic in articles for the Times-Democrat and later for Harper’s Weekly and the Atlantic Monthly. Many of these essays were collected into books.

Early on, Hearn was smitten with the writing of Shelley and French writers such as Maupassant and Flaubert. He dubbed himself “The Raven” after Poe. Hearn’s topics ranged from the ordinary to the bizarre and included everything from insect songs to creole recipes, the criminal mind, predictive dreams, and burial customs.

This was the man, and this was the background, and these were the fascinations that made up Hearn when he set off for Japan. Shortly after arriving, Hearn wrote “A Winter Journey to Japan” to pay for his trip. Infatuated with the people and the countryside, he described “the charm of Japan as intangible and volatile as a perfume.” He loved small-town Japan but wasn’t fond of cities, such as Tokyo, which he believed were corrupted by Western ways. In essays collected in Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan, he says as much, even as he covers everything from his climb of Mount Fuji to the Japanese smile.

In Japan, during its first era of modernization, he used his talent for language to, as he put it in a letter, “create a vivid impression of living in Japan — not simply as an observer but as one taking part in the daily existence of the common people, and thinking with their thoughts.”

During his 14 years in Japan, Hearn married Setsu Koizumi, a 22-year-old daughter of a Samurai family, with whom he had four children and became a Japanese citizen. He taught English language and literature in Japanese schools, colleges, and universities. He preferred to wear Japanese garb at home and sat on a mat on the floor. He was able to translate Japanese poems and rewrite Japanese folk tales, even though he spoke a pidgin Japanese and could barely read the Japanese language, because his wife conveyed the original stories and their meaning to him as they were going to bed.

He took the Japanese name Yakumo Koizumi and toned down his writing style, preferring the simplicity of Japanese writing. He wrote hundreds of articles explaining his views on Japanese subjects such as its religion, customs, culture, sports, literature, food, gardens, landscape, and birds. These are collected in 14 books the titles of which suggest Hearn’s unconventional interests: Kotto: Being Japanese Curios, with Sundry Cobwebs, Gleanings in Buddha-Fields: Studies of Hand and Soul in the Far East, as well as Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things.

His essays, widely translated into Japanese, offered a look into an older, more mystical Japan lost when the country was Westernized. The world saw him as a talented writer and an illustrious recorder of Japanese life. The Japanese considered him a literary icon. Hearn, as Kemme shows, was all that and more.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Diane Scharper is a poet and critic. She teaches the Memoir Seminar for the Johns Hopkins University Osher Program.