Larry McMurtry was right about everything except his own greatness

Peter Tonguette

Once, the great American novelists were synonymous with particular places in this large, unruly, complicated country, like landmarks on a map. Philip Roth was forever yoked to Newark, New Jersey, John Updike to rural Pennsylvania, Joan Didion was tied up with the Barry Goldwater-supporting pockets of California, and so on. These writers not only hailed from these places, they also made these places the subject of their work. In the process, they helped the Manhattan-centric literary world become a little less insular. They embodied the notion that great writers could be birthed in any town, city, burg, or remote outpost.

These days, the major novelists don’t seem especially interested in writing about where they are from. In so much fiction today, regionalism has been replaced by postmodernist tricks, needless irony, and fussy writing. The idea that a writer could emerge from the provinces to tell us plainly but humanely about his kith and kin seems quaint, almost antediluvian.

WERNER HERZOG’S MEMOIR REVEALS A GRIZZLY LIFE ALL TOO REAL TO BE CONCERNED WITH ANYTHING ABSTRACT

Chief among the hometown heroic writers is Larry McMurtry of Archer City, Texas, elegist for the fading pioneer spirit, satirist of what rose up in its stead, and self-proclaimed “Minor Regional Novelist.” (He had the slogan printed on a T-shirt.) McMurtry, who died in 2021 at the age of 84, realized early on that the accident of the location of his birth bequeathed him a lifetime of good material.

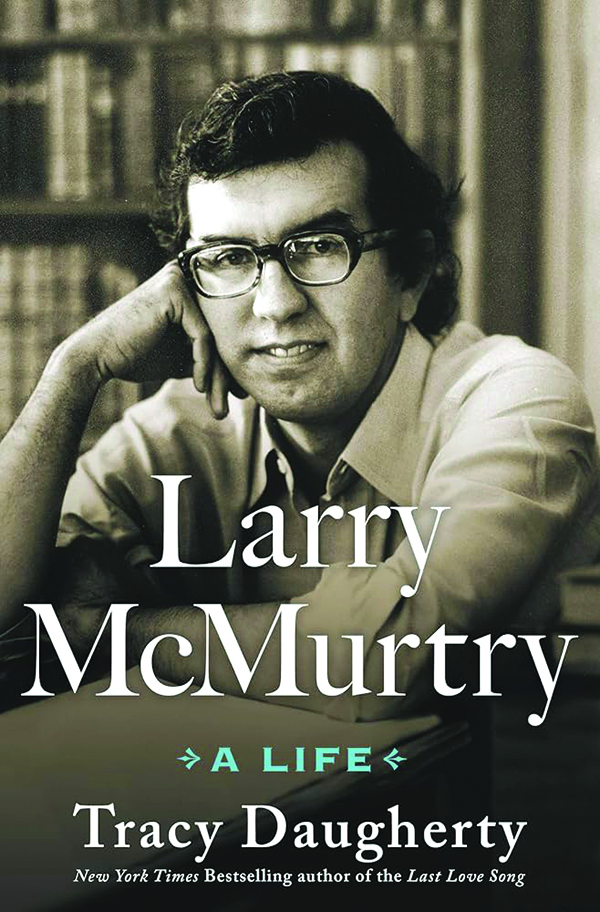

“In more than forty books, in a career spanning over sixty years, he staked his claim as a superior chronicler of the American West and as the Great Plains’ keenest witness since Willa Cather and Wallace Stegner,” writes Tracy Daugherty in his definitive new biography of the author.

The son of rancher William Jefferson McMurtry and his homemaker wife Hazel, Larry seems to have had a knack for reading the way that some children have a talent for climbing trees or wrangling steers. “I had only briefly been to school, and no one, that I can recall, bothered teaching me my ABC’s,” the author later recalled. “Yet I could read, and reading very quickly came to seem what I was meant to do.”

No less precocious by the time he had reached high school, McMurtry made common cause with a pretty, sophisticated girl named Ceil Slack, one of numerous female friendships he pursued and sustained throughout his life. “The things I loved most to do — like read, write, and sit around listening to porch stories — were not what normal [Archer City] school kids did,” said Slack, who could have been speaking for her classmate — already a devotee of Madame Bovary and Don Quixote. School librarians permitted McMurtry to steal books. Perhaps they reckoned that such thievery could be tolerated since at least it meant that someone in the town was reading.

In a book of prodigious size and scope, Daugherty follows McMurtry to Rice University in Houston, where the aspiring author tried his hand at poetry, short stories, and the start of what would become his first novel, Horseman, Pass By. He submitted an excerpt to the Southwest Review before withdrawing it for consideration in Esquire. He was scolded by the editor of the former for his “poor literary etiquette,” one of countless juicy behind-the-scenes details about the literary life included here.

One book at a time, the McMurtry theme took shape: The author was preoccupied with the ways in which the virtues of the West had become either outmoded or made counterfeit. In The Last Picture Show, movie theater proprietor Sam the Lion functions as a steadying force in a town otherwise overrun with middle-aged malcontents and adolescent sexpots, but even the old cowboy has lived too long to remain relevant. “Sam the Lion still lives by the code of the West, standing ‘tall in the saddle’ and trying to ‘do right,’ but his code has been reduced to a form of cheap entertainment at the picture show,” Daugherty writes, offering a deep understanding of the author’s intentions. McMurtry revealed himself to be profoundly preoccupied with the denuding of the emblems of the West, such as the rodeo circuit depicted in the superb Moving On: “The rodeo merely pantomimes ranch life; bull riding and barrel racing are just costumed Kabuki.”

Yet McMurtry’s fiction is not strictly backward-glancing. His female characters give his books much of their spirit and flavor. Foremost among them is Emma Horton, the gallant, sturdy, commonsense heroine of his masterpiece of the foibles and tragedies of gentrified Houstonites, Terms of Endearment. Daugherty superbly sketches the character of Emma, who, in his account, “largely accepts her lot in life, bowing to her mother’s wishes despite their awful arguments, refusing to leave her indifferent husband — and yet in some ways, she, too, does as she pleases.” Described in these pages as a watchful loner, McMurtry had an intuitive understanding of the complexity of people. “Every person has a story,” he said. “You respond to the potential and the contradictions.”

And so it was with McMurtry and his great subject: the lore of the land he came from and to which he felt compelled to return. Following three good novels that wandered from his natural terrain — Somebody’s Darling, Cadillac Jack, and the exceedingly good Las Vegas mother-daughter saga, The Desert Rose — McMurtry hit pay dirt with the first in a dazzling series of traditional Western novels, Lonesome Dove. He was awarded a Pulitzer Prize. Thereafter, he expressed a measure of fatalism about what remained of his life’s work, writing to Susan Sontag that “what’s left is just making a living, more or less respectably.”

Critics carped that he was hurting his cause by churning out fiction, even though his fans were delighted to learn the fates of the characters in The Last Picture Show and Terms of Endearment in various follow-up novels. “It’s not just that Mr. McMurtry has written his share of not-good novels. … He also tends to muddy the memories of his best ones … by writing sequels to them,” wrote Dwight Garner, unmoved, in the New York Times. Yet McMurtry, despite his own self-effacing modesty, could not help adding to his world of fiction any more than he could not be moved by the Texas sky, which he commemorated in All My Friends Are Going to Be Strangers: “It had such depth and such spaciousness and such incredible compass, it took so much in and circled one with such a tremendous generous space that it was impossible not to feel more intensely with it above you.”

McMurtry’s prolific output came to include essay collections, screenplays, and multiple interrelated book series. He was an old-fashioned writer who wrote to be read. No Salinger-Pynchon-Franzen elusiveness for him.

Daugherty describes McMurtry as being defined by voracity. He was not only a writer of books but an acquirer of books, an obsession that led to the establishment of his famous Booked Up bookstores in Washington, D.C., and Archer City. His devotion to his female friends was equally intense; among the ranks of women whose company and conversation he enjoyed were, improbably, both director Peter Bogdanovich’s first wife, production designer Polly Platt, and the woman Bogdanovich left Platt for, Last Picture Show leading lady Cybill Shepherd. Long divorced from his first wife, Jo, during the last decade of his life, he was married to deceased buddy Ken Kesey’s widow, Faye. McMurtry co-wrote a screenplay with his pal Diane Keaton, apparently in part for the fun of it; he embarked on a late-career writing partnership with Diana Ossana, with whom he shared in an Oscar win for the movie Brokeback Mountain. Touchingly, almost pleadingly, he confesses to Sontag in a letter how much he treasures their encounters: “I’ve been feeling not knowing you as a lack in my life for some time.”

Readers will put down this biography with a palpable feeling of the lack of a writer like Larry McMurtry in America today.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Peter Tonguette, a contributing writer to the Washington Examiner magazine, is writing a biography of Peter Bogdanovich.