The only era of Taylor Swift is adolescence

Derek Robertson

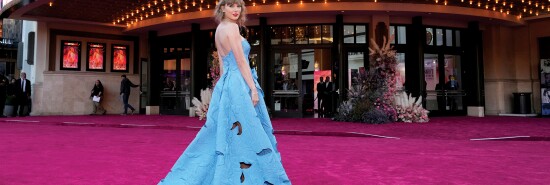

The Eras Tour, the film about the Taylor Swift concert series of the same name, is a victory lap, the theatrical capstone for a worldwide tour that will, by its end, have surpassed the GDP of many small island nations.

Her world domination — and the slack-jawed devotion she inspires in tween girls and otherwise sober, literary adults — is extremely easy to understand. She is a stunningly conventionally beautiful woman who has mastered pop music and the art of celebrity itself. Her songs, ballads and pop anthems alike, deliver the urgency and buoyancy that turn the humblest pair of headphones into a device capable of transforming one’s life into a grand romantic drama. She manipulates the media in a manner to put Latin American strongmen to jealous shame. She has outlasted her now culturally exiled true nemesis, Kanye West, an outcome that was once unthinkable.

DINING ROOM CONFIDENTIAL: WHY NEW YORK RESTAURANTS GET AWAY WITH BEING SO PRECIOUS

Swift is a winner, and she makes you feel like one, too. Her endlessly repeated superhero origin story, of catching her adolescent friends in the midst of a scheme to exclude her at a suburban Pennsylvania shopping mall, is relatable enough to anyone who’s ever suspected they just aren’t quite cool enough to maintain their tenuous social standing (that is to say, pretty much everyone in a post-scarcity consumer society). Everyone has been heartbroken, everyone has felt insecure, and everyone has wanted revenge. Swift follows the golden rule of pop music, telling her own stories with a hyperspecificity that somehow turns into communion.

Which is why her performances, and the manner in which they’re written about, can feel vaguely fascistic. “I don’t know if I could tell a story about Taylor Swift that’s better than the story she tells about herself, through every song, every dance, every video, every social transmission,” New York Times Magazine’s Taffy Brodesser-Akner wrote in a recent feature about the live tour. “She is a master not just at the revelation of information but the analysis of each revelation, the scrutiny of that analysis, the contextualization of it all.” The literal numerology deployed by her most devoted fans, convinced they alone can scry her intentions from slyly placed breadcrumbs, does not help the overall Ariosophic vibe of the Swiftie fandom.

“Criticism is superfluous,” the Washington Post’s Ann Hornaday wrote of the film. Even Paul Schrader, the hard-bitten auteur of broken men like Robert De Niro’s Taxi Driver, wrote in 2018 on Facebook: “About TS … let there be no doubt. She is the light that gives meaning to each to all our lives, the godhead who makes existence possible and without whom we would wander forever in bleak unimaginable darkness.”

Acknowledging the possibility of an extent to which Schrader’s tongue was somewhere in the vicinity of his cheek, let’s try to criticize the uncriticizable, just as a thought experiment: It’s hardly worth discussing The Eras Tour even in passing as a film, per se. Directed by big-ticket concert documentarian Sam Wrench, it alternates blandly between close-ups of Swift’s blinding visage, gratuitous medium shots of the gazillion-dollar stage show, and wide shots of SoFi Stadium in Los Angeles that resemble nothing so much as the awkwardly angled, low-detail virtual stadium shots in a Dubya-era edition of the Madden video game series.

You’re there for the songs, anyway. The titular “Eras” of the tour are (roughly) the 10 albums in Swift’s discography dating back to 2006, with each represented by a mini-suite and stage show in itself. Here as is now customary for this brand of Swiftoriography, I should acknowledge my own relationship with her music: As an early adopter of “poptimism,” or the belief that cultural tastemakers unfairly ignored the charms of mainstream pop music in favor of championing sometimes questionably worthwhile “difficult” underground music, I was won over by Swift with her catalog of winning, propulsive pop anthems such as “You Belong With Me,” “Love Story,” and my personal favorite, the U2-via-Forever-21 thumper “Holy Ground.”

It would be a joy, I thought, to follow this precocious young star over the course of her career as she refined her undeniable songwriting talent with the self-awareness that comes with age. This did not happen. Hardcore Swifties will fight you to the death, I suspect literally, to argue otherwise, but her subject matter is resolutely unchanged, dating back to her earliest work as a teenage songwriter. Misunderstood, occasionally troublesome, ultimately pure-of-heart women are failed by faithless friends or immature, sexy man-boys, only to persevere and enjoy the satisfaction of their integrity (and, of course, presumably win more faithful friends and mature, sexy boy-men, to judge from her real-life run of celebrity suitors).

Swift’s authorial style, too, has remained in arrested development. She was reared as a songwriter in Nashville, and her best work bears the alliteration, just-too-close internal rhyme, and folksy simile of her countrypolitan predecessors Tammy Wynette or Glen Campbell. Unfortunately, the other key ingredient in her songbook is a cringey, overly bantering teenage parlance of “hella good”-s, spoken word interludes, and some of the most unconvincing deployment of curse words this side of the Will Smith discography. This bag of tricks is all well and good coming from a 20-year-old, but it is frankly somewhat worrying coming from an artist old enough to start considering the benefits of a Roth IRA.

To experience this sameness over the nearly three hours of The Eras Tour is punishing. But it would have been more so if not for the key feature of the filmic Eras Tour experience, and what throws Swift’s embrace by mainstream tastemakers into bewildering relief: the screaming children. Children love Taylor Swift. An unkempt and generally disgruntled man on this particular weekend, I found myself in the midst of a throng of shrieking, joyful tween girls applauding, singing along, and actually dancing in the aisles, enough to bring a smile even to my own Grinch-like visage. Of course children love Taylor Swift: She’s beautiful but friendly, grown-up but kind of silly, and always good for a campfire singalong. Like a billionaire Mary Poppins, she bridges the worlds of childhood innocence and adult trouble, smeared together with a charming little ditty and spoonful of sugar.

This is why I am sorry to say, if for nothing else than the sake of my inbox, that her embrace by adult audiences is so profoundly disturbing. The most successful artist on the face of the Earth, Swift receives colosseum-surpassing applause every night by saying, “What, for me?” That’s not winningly humble; it’s phony. She drops Napoleon Hill-level cliches like “If you fail to plan, you plan to fail” into her lyrics and is lauded for it in Time magazine as providing her fans with a “feminist motivational call.” Wesley Morris, winner of the Pulitzer Prize for criticism, described her performance of the intolerably repetitive, fan-favorite 10-minute ballad “All Too Well” as like “watching someone woodwork ‘American Pie’ until it resembles ‘Purple Rain,’” the absurd hyperbole of which somehow dishonors every song involved.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

This is, admittedly, not really Swift’s fault. It’s not a cultural sin to write the same song over and over again, to lack self-awareness, or to simply be annoying. But the extent to which we are collectively expected to acknowledge her charm and genius at the point of a cultural bayonet is absurd and long overdue for a reckoning.

If her poptimist boosters choose to ignore this, or to read Byronic Romanticism into Swift’s moon-June-spoon world of knifelike cuts and “tight little skirts,” that’s their prerogative. But the rest of us don’t have to go along with it. To ask us as a culture to place her on the same plane as artists such as Prince, Joni Mitchell, or David Bowie, however — the plane of art, sex, death, humor, culture, and adulthood — is really just a bridge too far, at least for now.

Derek Robertson co-authors Politico’s Digital Future Daily newsletter and is a contributor to Politico Magazine.