The reissue of great spy novelist Len Deighton’s work is an occasion for another look

Malcolm Forbes

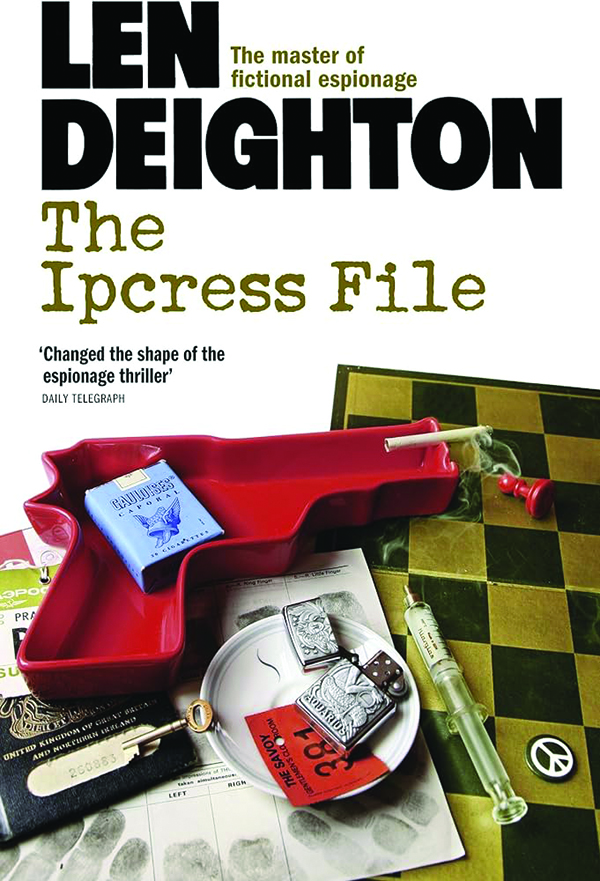

At the end of 1962, U.K. readers and audiences were introduced to two different kinds of British spy and two different depictions of the worlds they inhabit. In October, the first James Bond movie, Dr. No, hit the big screen. The following month saw the publication of Len Deighton’s debut novel, The IPCRESS File. The former was a glossy action-packed adventure in which Sean Connery’s suave yet deadly 007 went on assignment for Queen and country to Jamaica, where he enjoyed the company of beautiful women and came up against a criminal mastermind with metal hands. The latter was a grittier, more grounded affair narrated by an overweight, working-class spy who didn’t even have a name, let alone a code number, and who found himself in a torturous cat-and-mouse game involving brainwashing, a neutron bomb, and the disappearance of top biochemists. “It’s a confusing story,” he explains at the outset. “I’m in a very confusing business.”

Deighton’s book became a bestseller. Dr. No’s co-producer Harry Saltzman promptly snapped up the rights and assured Deighton that he wouldn’t make “an imitation Bond film.” He couldn’t have even if he’d tried. For with The IPCRESS File, Deighton presented the flip-side to Bond in the form of an anti-establishment anti-hero who doesn’t get the girl and save the world. His “confusing business” contains high-stakes drama, artful manipulation, and epic betrayal, like Bond’s, but it also contains moral ambiguity. In the 1965 movie, Michael Caine’s character was given the name Harry Palmer. “My name isn’t Harry,” says the protagonist in the book, “but in this business it’s hard to remember whether it ever had been.” His thick, black-framed glasses, cockney accent, cynical outlook, and preference for home cooking over fine dining consolidated Deighton’s vision of a no-frills, down-to-earth regular Joe.

Deighton’s debut radically revamped the modern spy novel. The only other work that can stake such a claim is John le Carré’s The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, which was published one year later in 1963. Deighton, like le Carré, went on to enjoy a long and distinguished writing career, producing a steady stream of thrillers. Naysayers will sniffily dismiss them as low-brow popular fiction. The rest of us will regard them as carefully crafted literary fiction — intelligent books packed with grit, wit, sharp dialogue, and well-drawn characters, books that explore geopolitical tensions, class division, and the human capacity for secrecy and subterfuge while maintaining high levels of intrigue and suspense.

The IPCRESS File is one of several Deighton books that has recently been reissued by Grove Press. More batches will be republished over the coming months until all 31 of his main titles are available. It is a laudable project, one that will result in new generations of readers discovering him and old admirers revisiting him. Whether sampling him for the first time or the second, it doesn’t take long to become captivated.

Deighton was a masterly author right from the start, a remarkable feat for someone who claimed to have “stumbled into writing” after spending years showcasing another talent. Deighton was born in London in 1929. The outbreak of war interrupted his education, and he left school early. At the age of 17, he was conscripted into the Royal Air Force. In 1952 he won a scholarship to the Royal College of Art. After graduating, he “impulsively” applied for a job as a flight attendant with British Overseas Airways. He later returned to his love of art, working first as an illustrator in New York and then as art director of a London advertising agency. His creative output was vast: He drew and designed for magazines such as Esquire and illustrated over 200 book jackets.

Then one day in 1960, while living in France and working as a freelance illustrator, Deighton picked up a fountain pen and began to write. Soon he was devoting his evenings to writing. His novel took shape, and two years later, he was a published author. Rather than rest on his laurels, he got to work on his next book and then the next.

“Writing books is like a spell on the battlefield,” he once wrote. “For the first two or three books you survive largely by luck. After that the odds are against you, and you have to learn quickly and learn by narrow escapes.” For four decades, Deighton showed himself to be combat ready and battle hardened. He was, by his own admission, an obsessive writer, working on novels seven days a week and even clocking in for a couple of hours on Christmas. He was also a meticulous writer, enriching his tightly plotted narratives with technical, historical, and even culinary detail and bringing characters to life by way of intricate file indexes.

Above all, Deighton was a prolific writer, and not just of spy fiction. Among the many spook-free novels slated for reissue are the sprightly caper Only When I Larf from 1967, about a trio of confidence tricksters, Close-Up (1972), a searing exposé of the movie industry, and Deighton’s least representative work MAMista (1991), involving a rumble in the South American jungle with Marxist guerrillas. History enthusiasts and military buffs can look forward to the rerelease of Deighton’s excellent nonfiction books on World War II: Fighter (1977), Blitzkrieg (1979), and Blood, Tears and Folly (1993).

But it is for his gripping novels about world war and Cold War that Deighton will be remembered. After his run of spy novels in the ’60s and ’70s fronted by an anonymous everyman, Deighton changed tack in 1983 with Berlin Game, employing a fleshed-out first-person narrator that had an identity, a personality, a backstory, and an agenda. Former British field agent turned desk-man Bernard Samson is roused into action and sent on “another jaunt to Big B” to bring Brahms Four, a key intelligence asset, over the Wall and through the Iron Curtain to safety. Meanwhile, a KGB mole in London Central hemorrhaging secrets has the power to sabotage Bernard’s mission and overturn his life.

This was no stand-alone novel but rather the first riveting installment in a triple trilogy. Deighton’s sprawling spy saga was an ambitious project pulled off with aplomb. In each book, his cast members make their presence felt, from “sardonic bastard” Bernard to resourceful wingman Werner Volkmann to Berlin station chief Frank Harrington, who knows “every square inch of this stinking town, from palace to sewer.” The city is more than a backdrop in the Samson books: it is also an ever-present character. According to Deighton, Berlin “hovers over the action like a storm cloud even when the action moves to a different locale.”

Two of Deighton’s longest novels constitute career highs. Winter (1987), a prequel of sorts to the Samson series, chronicles the fortunes of a Berlin family from 1899 to 1945 through the divergent trajectories of two brothers — one who becomes seduced by Nazi tyranny, the other who stands up against it. Equally expansive and immersive is Bomber (1970), which, through rotating perspectives, follows British airmen and German civilians living on borrowed time over the course of 24 fraught hours in 1943. “I’m interested in what happens to people. I come from a long line of humans myself,” says one jaded pilot.

In 1978, Deighton tried a markedly different sort of wartime novel. Like Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle before it and Robert Harris’ Fatherland after it, SS-GB imagines an alternative world in which the Nazis triumphed. It is 1941, and Winston Churchill has been executed, and the king awaits his fate in the Tower of London. Scotland Yard detective Douglas Archer navigates bombed streets, vengeful resistance fighters, and the machinations of his new SS superiors in his hunt for a murderer. Can he solve a crime that becomes a political matter and stay sane while “the repressive, death-dealing machinery of the Nazi administration” ratchets up a gear?

Deighton is now 94, but he hung up his pen decades ago. Unlike le Carré, who wrote until the end, publishing novels of varying quality in his twilight years, Deighton quit while he was ahead. There may not be any new work coming our way, but at least we have the delights of his back catalog.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Malcolm Forbes has written for the Economist, the Wall Street Journal, and the Washington Post. He lives in Edinburgh.