Defining Webster

Carl Paulus

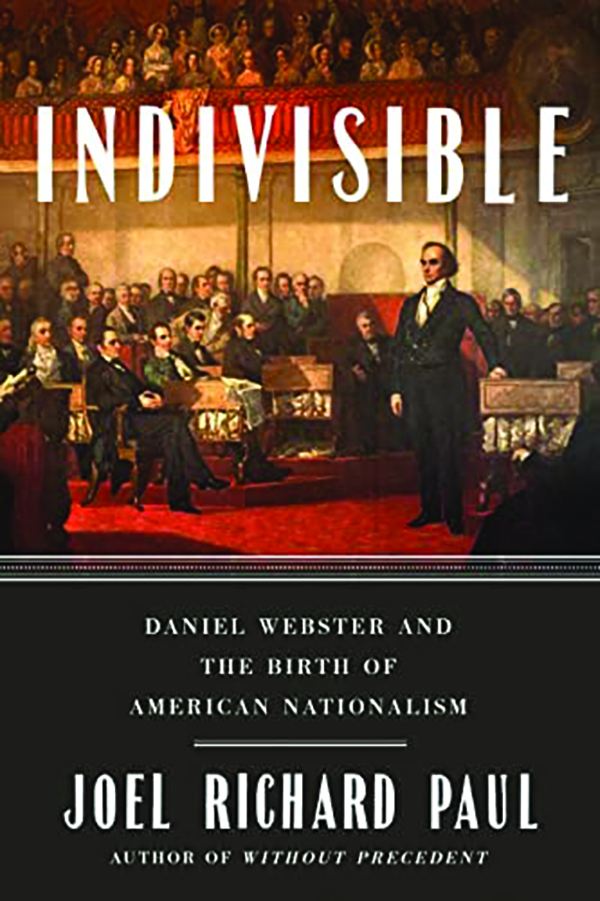

Joel Richard Paul’s Indivisible: Daniel Webster and the Birth of American Nationalism seeks to pull from our past different concepts that affect our politics today, particularly populism and nationalism, by telling the story of how “while the Union was falling apart, our American identity was taking place.” He credits New England statesman Daniel Webster as the primary driver of the “national constitutionalism” that helped prop up this identity by serving as “an antidote to Jackson’s toxic populism” and the state-compact version of nationalism espoused by Thomas Jefferson.

The third member of the Senate’s “Great Triumvirate” alongside Henry Clay and John C. Calhoun, Daniel Webster remains an under-discussed figure of antebellum America. Twice secretary of state and twice declined the offer of a vice presidency from presidents who later died in office, Webster was an ardent defender of the Union. Standing before the Supreme Court, he made the argument on behalf of the power of the federal government in some of America’s most precedent-setting cases. In the Senate, he gave some of the most eloquent and compelling speeches in American history.

In portraying Webster as the primary driver of “national constitutionalism,” however, Paul often twists himself in a knot. Although he admires the Massachusetts senator, Webster often disappears from the narrative as the author takes long asides, trying to define what nationalism means or how the United States had different strains of nationalism devised by people rather than occurring organically. Paul’s “nationalism,” like his “populism,” is nebulous. These terms end up being a little more than vehicles to criticize historical actors the author despises, such as Andrew Jackson and Donald Trump — whom he often ties together by making not-so-subtle depictions of the former in modern terms used to describe the latter.

Indivisible offers some entertaining background to one of America’s greatest senators, and his asides discussing literary movements under the context of American nationalism are fascinating. But there are certain off-putting errors. For example, he argues that the Creole case, a slave revolt on a ship in 1841, created the alliance between American and British antislavery movements. But that association happened decades before. Similarly, he alleges that William Henry Harrison’s inaugural did not give “the slightest indication of what he planned to do as president,” when in fact, the ninth president’s infamously long speech clearly laid out his agenda and approach to the office.

Paul often stumbles in attempting to make a coherent argument because he, to paraphrase American Historical Association President James Sweet’s words from a recent essay, interprets history through the optics of the present rather than locating his study “within the worlds of our historical actors.” Everything Paul dislikes about the past, or as he puts it, everything that “threatens pluralist democracy,” is often labeled as “populism,” which he says is not “based on any coherent ideological appeal so much as on a cult of personality. Populists span the political spectrum: Andrew Jackson, Huey Long, George Wallace, Donald Trump, Boris Johnson, Marine Le Pen, Hugo Chavez, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, and Viktor Orban.” After writing those lines in his introduction, he then spends several chapters discussing Andrew Jackson’s ideological appeal while calling it “populism.”

Looking past Webster’s life to emancipation during and after the Civil War, Indivisible misses the mark because it conflates the Union with the U.S. government, or what Paul calls “constitutional nationalism.” The author finds Webster’s famous words of “liberty and union, one and inseparable” to be a stumbling block because the issue of slavery and the removal of Native Americans meant that it was never true. But for Webster and his contemporaries, including Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass, those words made perfect sense.

The Union incorporates both the federal government, states’ rights, and the preservation of individual liberty. One could not exist without the others. No contradiction exists between states’ rights and national constitutionalism because the Constitution preserves states’ rights. Individual liberty could best be expanded within the Union because of the protections it provided.

Nothing better exemplifies Paul’s misunderstanding of the concept of liberty and Union, along with his faulty presentist interpretation of past events, than his discussion of the Compromise of 1850 and Webster’s role in accomplishing it. “The life of every great figure ends in tragedy, but the particular tragedy of Webster’s life was also America’s tragedy,” he writes. Focusing solely on the fugitive slave aspect of the compromise, the author contends that Webster was “forced to conclude that union could only continue if human liberty were sacrificed.”

This interpretation pulls Webster and his contemporaries out of their historical time and ignores the antislavery discussions and shifting political calculations in that period. During the 1840s, the antislavery movement was driven by a belief that United States slavery would die if it could not spread to new territories across the continent. By trading an unenforceable fugitive slave law (states’ rights) for ending slavery’s spread across the continent and bringing the new free state of California into the Union (the federal government), the Union was preserved, allowing for the possibility of liberty being expanded. Webster’s final public actions were not a tragedy but a triumph for his argument that liberty and Union were inseparable. The following 15 years rewarded his faith in that belief.

At times, Paul seems to be indulging in a need to tear down Webster’s peers to make his hero seem larger than life. Those looking to understand why the Union meant so much to people like Daniel Webster and how such a belief propelled northerners like Abraham Lincoln to fight a civil war for its preservation will be left wanting more.

Carl Paulus is a historian from Michigan and author of The Slaveholding Crisis: The Fear of Insurrection and the Coming of the Civil War.