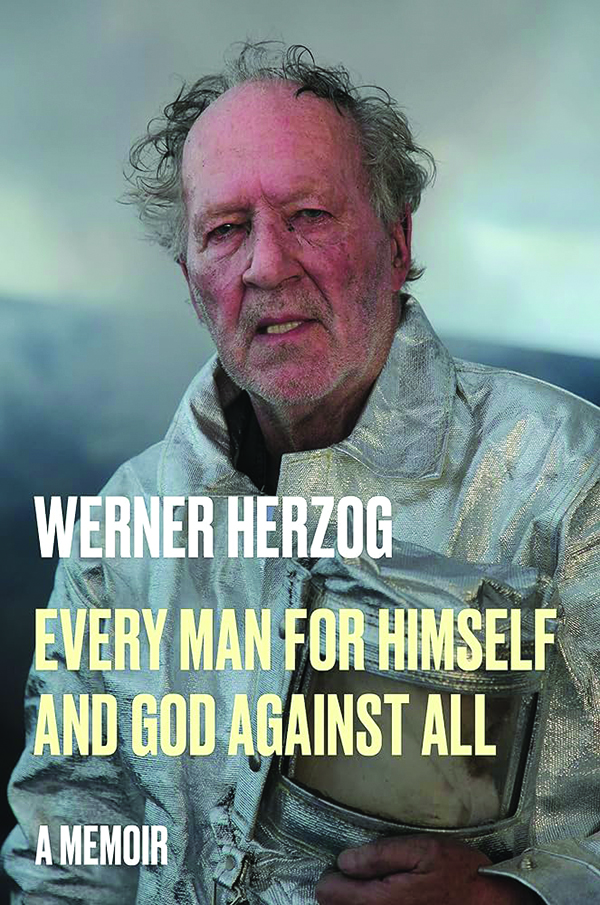

Werner Herzog’s memoir reveals a grizzly life all too real to be concerned with anything abstract

J. Oliver Conroy

Being Werner Herzog, or just working with him, may be an occupational hazard. In his baroquely titled new memoir, Every Man for Himself and God Against All, the German filmmaker describes almost dying many times. His casts and crews fare little better: A single production in the Amazon suffered an attack by hostile tribesmen who near-fatally gored several crew members with 6-foot-long arrows, a poisonous snake bite, and two plane crashes, one of which left someone paraplegic. The bitten man, knowing he had only a minute before the venom reached his heart, amputated his own leg with a chainsaw. Those wounds used the last anesthetic, so when an accident split a cameraman’s hand, a prostitute soothed him by holding his head between her breasts. One of Herzog’s star actors, the notorious Klaus Kinski, once started shooting at colleagues with a rifle. Thankfully, the only casualty was a finger.

If Cormac McCarthy had taken up a video camera instead of a typewriter, the result might have looked something like Herzog’s films. His dozens of documentaries (Wings of Hope, Grizzly Man, Into the Abyss, and Into the Inferno) and dramatic features (Aguirre, the Wrath of God, Fitzcarraldo, Rescue Dawn, and Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans) are preoccupied with the elemental and the primal. Man versus nature, man versus madness, and civilization versus anarchy: Herzog is interested in the brink and the things beyond the brink. After lending his nasal German-accented narration to the twists and turns of so many other people’s lives, Herzog, in this memoir, gives a delightful look at a personality drawn to artistic and physical risks.

REVIEWED: WILLIAM FRIEDKIN’S THE CAINE MUTINY COURT-MARTIAL

Like Dieter Dengler, the German-born American airman who is the subject of Herzog’s 1997 documentary Little Dieter Needs to Fly, Herzog’s early life in wartime and postwar Germany was marked by extreme privation. His parents were both “early, committed members of the Nazi Party,” though his mother later renounced her views. Herzog’s father, the son of a respected archaeologist, was a womanizer and layabout with academic pretensions who claimed for years to be working on a brilliant opus that did not exist. Herzog’s mother held a doctorate but was forced to raise him and his brother in poverty and mostly without their father’s help.

After they narrowly survived an Allied bombing, Herzog’s mother decided to evacuate the family from Munich to a tiny Bavarian village in the Alps. They lived in a farmhouse without electricity, running water, or an inside toilet, and they sometimes went without food. When an American soldier gave him a piece of gum, young Werner chewed on it “for weeks.” Herzog writes about this period with an admirable absence of self-pity and, if anything, considerable fondness. Left to their own devices, the children ran wild. Werner once stabbed his brother during an argument over a pet hamster, leaving the room “awash in blood” and prompting him to do some soul-searching. To this day, Herzog and his brother maintain a raucous comic grammar “baffling to outside observers.” They do things like quietly set each other’s clothing on fire while dining in restaurants with their families.

Herzog’s family later moved back to Munich, where he attended a rigorous prep school. He was an indifferent student but befriended some intense and charismatic classmates — including Rolf Pohle, who later joined the left-wing terror group Red Army Faction, also known as the Baader-Meinhof Gang. He also first met the “madman” actor Kinski, who lived in the same boardinghouse. By university, Herzog had realized that conventional bourgeois life was not for him: He was more interested in hiking and hitchhiking around Germany and planning a disastrous trip to Africa, where he wanted to see the newly independent Congo but fell sick and was forced to turn back.

A visit to England polished Herzog’s English, and a camera purloined from the Munich Film School provided the initial armament for his artistic ambitions. He briefly moved to Pittsburgh to study at a college there but realized it was a dead end and illegally migrated into Mexico when his U.S. student visa lapsed. He spent some time south of the border, selling black-market goods to rancheros before eventually returning to the United States. And from there to Europe, where he started his filmmaking career in earnest, often with considerable bootstrapping.

Along with Wim Wenders, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Wolfgang Petersen, and others, Herzog became associated with the New German Cinema, an indie movement of ambitious, low-budget pictures. Herzog’s memoir goes a long way toward articulating his own vision of filmmaking, which is grounded in an obsession with anthropological questions about society, history, technology, and speech, as well as a pursuit of artistic truth over strict literality, which has sometimes drawn criticism from fly-on-the-wall, cinéma vérité-style documentarians.

Herzog’s memorable responses to his artistic critics — “Let them fact-check to their death”; “Happy New Year’s, losers” — might be said to describe the tone of the memoir, which is candid about his faults and the errors he’s made along the way but also uninterested in the kind of handwringing dissection that hobbled the documentarian Louis Theroux’s 2019 memoir. Herzog has had a somewhat messy personal life — he has been married three times and has a child with three different women — and he acknowledges that his industrious (and dangerous) career has sometimes put a strain on his family. He declines, for better or worse, to go into much detail. He characterizes himself as so uninterested in “navel-gazing” that he does not know his eye color and almost never dreams while sleeping.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Where Herzog comes most alive in this memoir is in describing his unusual childhood and the eccentric adventures of his work-obsessed life. For Herzog, the work is everything, and the book even goes into detail describing several ideas he’s long wanted to execute but never been able to. Fans of the vivid family memoirs of Alexandra Fuller (Don’t Let’s Go to the Dogs Tonight) and André Aciman (Out of Egypt) will enjoy Every Man for Himself and God Against All, as will anyone interested in filmmaking and documentary journalism.

Herzog writes of his shock at visiting a recent film set and seeing the young crew members “flee in terror” from some cockroaches. His advice for aspiring filmmakers has a more guerrilla sensibility: Carry a lockpick kit. You never know when it might be useful.

J. Oliver Conroy’s writing has been published in the Guardian, New York magazine, the Spectator, the New Criterion, and other publications.