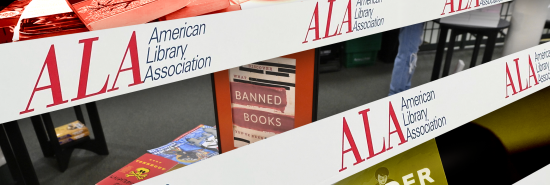

How the American Library Association is censoring clarity

Micah Mattix

The annual event in which a few librarians and journalists try to convince us that censorship is a real and dangerous problem in the United States is finally over. Thank God.

Banned Books Week is always accompanied by a good deal of misinformation and fearmongering. The name of the week itself is an abuse of language. The “banned” books on the list that the American Library Association has published every year since 1982 are neither banned nor censored. They are books that parents and taxpayers have requested be removed from schools or public libraries. The books remain widely available online and in bookstores — at least until they appear on the ALA’s list. Being a banned book has never been so good for sales, and some bookstores can’t keep up with demand.

THE PARANOID STYLE IN LIBERAL CRITICISM

The numbers the ALA shares every year are also cooked. The 1,269 book “bans” the ALA reported in 2022 are not actually bans but “challenges” — requests to remove materials. You might think a “challenge” is always a request in writing to remove a book. But it is also a mere verbal complaint. These 1,269 requests and complaints were reported as an “unparalleled” increase from 2021, almost double. That sounds concerning until you learn that there are nearly 120,000 libraries in the U.S. That’s about one request to remove or one complaint for every 100 libraries. No doubt many of these requests are based on judgments I or readers would not agree with, but the point is that the impression of the overall picture of the banning of printed, bound words given by the ALA’s communications, along with the widespread press coverage about trends in book-banning, is a false one.

The ALA blames “a vocal minority” for stoking “the flames of controversy around books,” which has led to this troubling increase in complaints that now touches a little over 1% of libraries across the country. Deborah Caldwell-Stone, the head of the ALA’s Office for Intellectual Freedom, thinks that people sharing information freely on social media is largely to blame for these unprecedented attacks “on every person’s constitutionally protected right to freely choose what books to read.”

Requests to remove books such as Gender Queer, a graphic novel that includes scenes of fellatio and gay sex, are reported in media outlets such as the New Republic as attacks on our very democracy (notwithstanding that the New Republic’s Alex Shephard can be found in that magazine’s pages as recently as 2021 defending bans of Dr. Seuss books that actually saw certain titles rendered virtually impossible to buy). This year, liberal writers were particularly distraught. Melissa Gira Grant complained in the New Republic about a wave of parents flooding school board meetings, “propagating their commentary online,” and “speeding up the cycle of theatrical grievance-mongering.” In the New York Times, Margaret Renkl wrote that requests to remove sexually explicit materials were a “crime against democracy” and suggested that they have caused over a quarter of a million teachers and librarians to leave education altogether: “The attacks have been so relentless and so demoralizing that some 300,000 teachers and librarians have left the profession.”

Being a parent myself and having listened to parents talk about their children’s education, I find it entirely plausible that some mothers and fathers are overreacting. Parents have always worried about what their children see and do outside the home. They have always worried about their children having sex. Still, however much parental fears about sex may have contributed to the current book ban fever, they don’t hold a candle to the hysteria of the ALA and commentators like Renkl.

I spoke to Pat R. Scales, a former middle school teacher and the onetime chairwoman of the ALA’s Intellectual Freedom Committee. She is the author of the ALA’s Teaching Banned Books, Books Under Fire, and Banned Books for Kids: Reading Lists and Activities for Teaching Kids to Read Censored Literature. She told me that she first published Teaching Banned Books in 2001 to encourage a conversation about books that were removed from library shelves. “I think we’re making a mistake when we’re banning books and not having a conversation,” she said.

Teaching Banned Books was updated and reissued in 2019 before many of the more controversial titles, such as Gender Queer and All Boys Aren’t Blue, were published. When I asked her if she would include these titles in a future update, she said she would, but she said that she would not recommend Gender Queer for all students. “Gender Queer was written as an adult book. Do I think it should be in high schools? Absolutely,” she told me. “But I would never recommend it for elementary school. I would never even recommend it for middle school.”

Scales said she was not aware of Gender Queer being recommended to elementary school students, but the book has been made available to both elementary and middle school students in some districts.

While Scales blamed “unreasonable” parents for stoking what she thinks are unfounded concerns about sexually explicit books, she also said that libraries and bookstores have “caused some of our problems” by thinking of fifth graders as young adults. “There is nothing about a fifth grader that is a young adult. I would even argue that middle schoolers are not really young adults. They are entering their adolescence. … Why would we call an 11- or 12-year-old a young adult?” It is “a huge error,” she said.

There is a great deal of confusion about which books are available for which grades in school districts, especially books that contain explicit images and frank descriptions of sexual acts. If the ALA wanted to have an honest conversation about the appropriateness of certain books, a good start might be to report how many of the 151 requests to remove Gender Queer or the 62 requests to remove Flamer originated at elementary or middle school libraries.

The ALA might also consider avoiding inaccurate words such as “ban” or “censor” and use Banned Books Week to focus on books that have actually been banned. It might not create as much publicity as the current iteration of Banned Books Week. But it might be better, you know, for our democracy.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Micah Mattix is a professor of English at Regent University.