The president is responsible for the conduct of his agents in the Justice Department

Jay Cost

Former President Donald Trump has now been indicted four separate times: once in New York, once in Georgia, and twice in federal court, the latter two being pursued by the Department of Justice. Despite claims to the contrary, the Department of Justice is not an independent agency like the Federal Reserve or the Federal Trade Commission. Its senior officials are appointed by and responsive to the president of the United States, in this case Joe Biden, Trump’s previous and quite possibly future political opponent.

That raises the inevitable question: Is this prosecution political? Fox News host Jesse Watters certainly thinks so. In a monologue on his show in late August, he argued that Biden is “personally running the prosecutions of Donald Trump,” basing that on White House visitor logs that show a top Justice Department official involved in the Trump investigations meeting with Biden’s deputy chief of staff. Watters, of course, is left to infer what the content of those meetings was, and he’s inclined to suspect the worst.

TRUMPISM 2.0: HOW REALISTIC IS DONALD TRUMP’S 2024 PLATFORM?

Minimally, it is fair to say that the White House has been applying indirect pressure on the Justice Department. According to the New York Times, Biden told his “inner circle” in January that Trump should be prosecuted and that Attorney General Merrick Garland needed to “act less like a ponderous judge and more like a prosecutor.” Five days after that report was published, sure enough, the Justice Department sent word that it had opened an investigation into how the former president handled classified documents at his Mar-a-Lago estate.

There are more signs of politicization. Consider the indictment of Trump over his actions on Jan. 6, 2021. What Trump did on that day was disgraceful, but criminal? As National Review’s Andy McCarthy pointed out, that requires “tenuous legal theories” that set a “dangerous” precedent in criminalizing politics. That this case will go to trial in an election year makes it hard to reject the notion that this is all a purely dispassionate pursuit of justice.

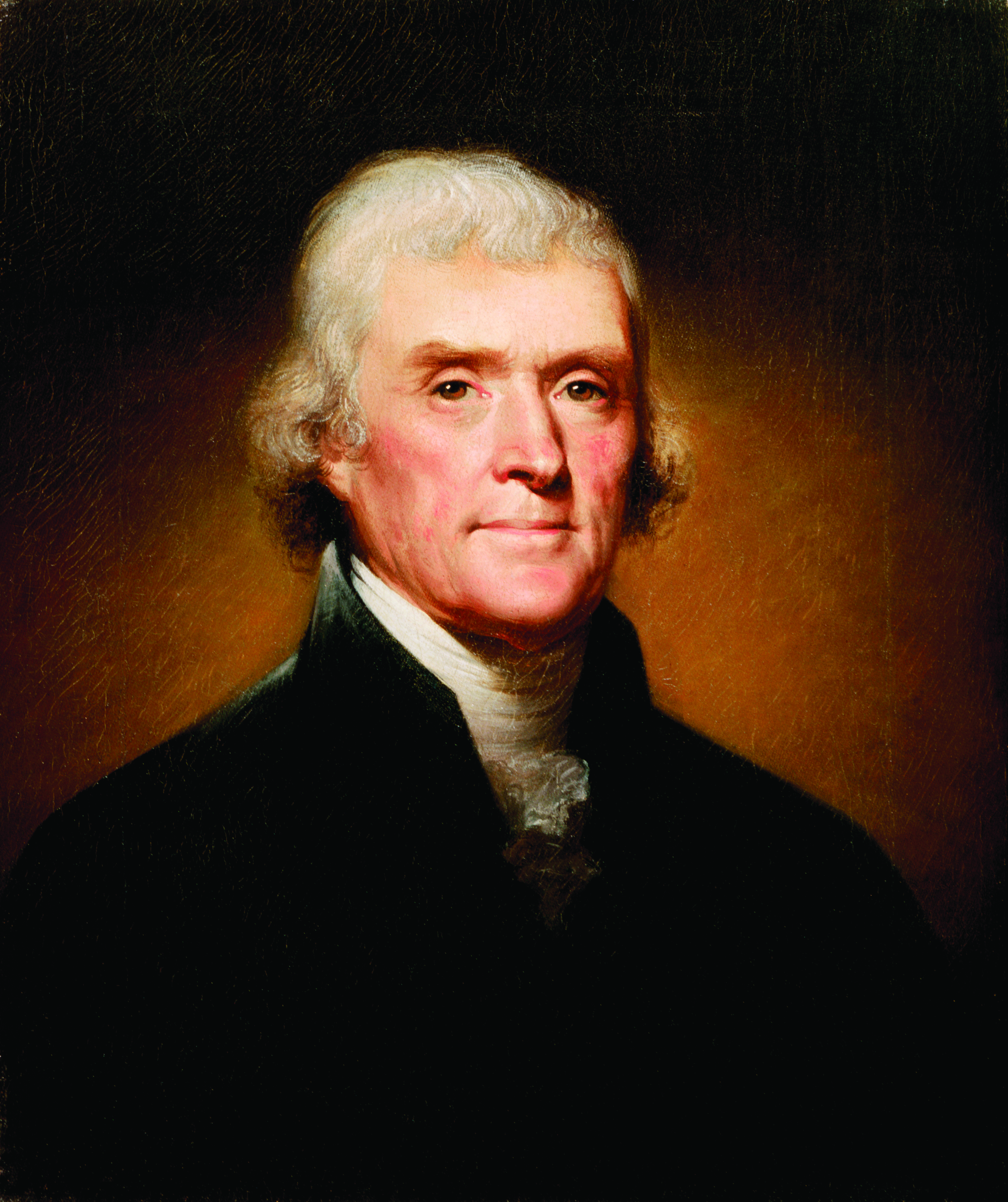

Even so, this would not be the first time that the president has involved himself in affairs of justice against political opponents. Prior to Trump, the most notorious example was the rivalry between President Thomas Jefferson and his former vice president, Aaron Burr — a case that can provide some insight into the current situation.

In the 1790s, Burr emerged as a political impresario in the Jeffersonian Republican Party. As a senator from New York, Burr earned a reputation for being a staunch opponent of the Jay Treaty of 1795, which forged an alliance with Great Britain — at the expense, the Jeffersonians claimed, of American pride. That, plus the fact that he was from New York, earned him a spot as Jefferson’s vice presidential candidate in the 1796 election. The Jeffersonians lost, but over the next four years, Burr was an intrepid and creative political organizer, developing a proto-political machine in New York City to help deliver the state’s electoral votes to Jefferson in 1800. Again, to create balance on the Republican ticket, Burr won the vice presidential nod.

Yet Burr had a reputation as an overly ambitious, grasping politician. Back then, a gentleman was not supposed to be so open about his pursuit of power. Burr never tempered his covetousness, which turned out to be his political ruin. The original design of the Electoral College was for electors to cast two votes for president, rather than one for president and one for vice president. The Jeffersonians dutifully cast one ballot for Jefferson and one for Burr, so the party would have both top vote-getters. This resulted in a technical tie between the two.

Despite the fact that everybody involved had intended Jefferson to be president, Burr saw an angle. Under the rules set forth in the Constitution, the House of Representatives breaks Electoral College ties, and the Federalist Party, which had nominated John Adams and lost, still held the balance of power in the House vote. Burr began negotiating with Federalists to swing the presidency to him, and it was thanks in part to the intervention of Alexander Hamilton that Jefferson prevailed. Hamilton disagreed vehemently with Jefferson on principle, but he believed that Burr was a man bereft of principle.

And as fate would have it, Burr would slay Hamilton three years later. Burr’s treachery left him a persona non grata as far as Jefferson was concerned, and in 1804, the Republicans replaced him with George Clinton, another New Yorker, as vice president. Burr decided instead to run for governor of New York, a race that he lost. And he held a grudge against Hamilton, who it was claimed by a New York newspaper had denounced his character. When Burr wrote to Hamilton to clarify his meaning, Hamilton was highhanded about it, refusing even to answer his question. A series of letters followed as the two men upped the rhetorical ante, until they agreed to a duel in nearby Weehawken, New Jersey. Duels were not uncommon during this period, although they were increasingly illegal, and often, the men just fired their guns away from their opponents, wasting their shots but preserving their integrity. In this case, however, Burr killed Hamilton, ruining whatever political capital he may have had left.

Shorn of all credibility in government, in 1806 Burr set out to redeem himself in the West. Spain remained a major rival of the U.S. in the West, controlling both Florida, which it refused to sell despite American offers to buy, and the land west of the Louisiana Purchase. Burr traveled to New Orleans and cooked up a half-baked scheme to pick a fight with the Spanish. To that end, he recruited an old comrade of his from the Revolutionary War, James Wilkinson, who was still in the military and now tasked with defending American interests in the southwest. Burr also began toggling between negotiations among the governments of the U.S., Spain, and Great Britain.

By early 1807, Jefferson became convinced that Burr was engaging in treason, thanks in no small part to the account of Wilkinson, who, according to historian Forrest McDonald, was “perhaps the most treacherous and scurrilous of all the scoundrels and adventurers who infested the southwestern frontier.” Jefferson sent a letter to Congress announcing that Burr was the “prime mover” of “agitation in the western country, unlawful and unfriendly to the peace of the Union.”

Jefferson declared Burr guilty without even a jury having indicted him, let alone convicting him. And perhaps unsurprisingly, a grand jury in Jefferson’s home state of Virginia duly indicted him, with the trial overseen by Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall — who, under the Judiciary Act of 1789, was tasked with riding circuit. According to historian Kent Newmyer, Jefferson “micromanage[d]” the government’s prosecution, but it was hampered not only by an overreliance on the testimony of Wilkinson, who was widely believed to have been in cahoots with Burr and who would go on to disgrace himself as a commanding officer in the War of 1812, but of the magnetic personality of Burr, whose defense was vigorous and effective. The jury acquitted him. And while his political career was over, he walked away a free man.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

What lessons can we draw from this? First, the notion that the pursuit of justice in this country is apolitical is legally and historically fanciful. The Department of Justice is responsive to the demands of the president, which is as it should be. Nobody in their right mind could possibly want an independent prosecutorial force in this country — unconstrained from the political branches and, by extension, the people of the U.S. Jefferson and Biden both made clear their preferences, and their prosecutors responded accordingly.

Second, the president is ultimately responsible for the conduct of his agents in the Justice Department. Jefferson, in historical retrospect, must take responsibility not only for his hasty declaration of Burr’s guilt but also for the farcical trial that followed. Likewise, Biden must be held responsible for the pursuit of Trump. The president has clearly indicated what he thinks of Trump, and as Harry Truman once put it, “the buck stops” with him. If the Department of Justice is straining the law to make a case against Trump for Jan. 6 or pursuing him aggressively for his retention of documents, and all this in advance of a presidential election, that’s on Biden.

Jay Cost is a visiting fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and a visiting scholar at Grove City College.