What France really surrendered

Sean Durns

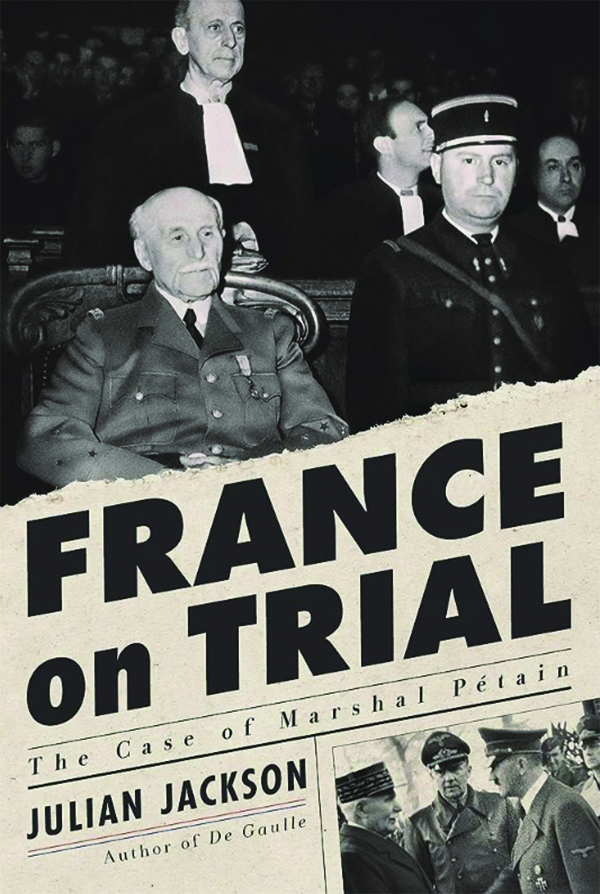

“Treason,” the Napoleonic-era diplomat Talleyrand famously remarked, “is merely a matter of dates.” Yet it is really about so much more, as Charles de Gaulle biographer Julian Jackson illustrates in his new book, France on Trial: The Case of Marshal Pétain. Jackson deftly uses the trial of the French World War I hero-turned-Nazi collaborator Philippe Pétain to explore France’s role in World War II and the Holocaust, as well as the nation’s struggles with memory and responsibility.

In October 1940, following a sharp and painful defeat to the Nazi Wehrmacht over the summer, Pétain shook the hand of Adolf Hitler. A famed military hero of World War I, the 84-year-old Pétain had been installed as the head of the Vichy state, the collaborationist regime the Nazis had created. The two-hour meeting was “inconclusive,” Jackson notes, but its “symbolic impact was incalculable.” To help his countrymen navigate the new set of circumstances, Pétain was offering “the gift of his person.” Humility was not among his faults.

CHICAGO LAWMAKER LEADS DEMOCRATIC REBELLION TO BRING IN ICE AND STOP IMMIGRANT SURGE

France, which had spent more than four years and more than a million lives defeating Germany in the last war, was being subordinated and subjugated by its historic enemy. In a subsequent speech, Pétain called for a “collaboration” with the Nazi regime, a collaboration that “must be sincere.” It was, he told listeners, “my policy,” adding: “It is I alone who will be judged by history.”

And history is a harsh judge, Jackson’s book makes clear. At the war’s end, with France liberated and Nazi Germany defeated, Pétain’s countrymen would sit in judgment of the old general and other leading figures of Vichy. There was, Jackson notes, “a thirst to understand exactly what had happened in 1940 when France had been defeated and French democracy had been swept away.”

The country would seek to quench that thirst over three weeks in a sweltering Paris courtroom. In theory, Pétain’s trial for treason offered the country, bloodied, battered, and humiliated from four years of occupation, an opportunity to explore what had happened and why. It was, one historian alleged, more of “an elaborate ceremony aimed at symbolically condemning a policy” — the policy of working with, indeed actively aiding, the Nazi regime. The early days of the trial were less about Pétain and more about reckoning with what had transpired in the country. As one French newspaper remarked at the time, “We are listening to ghosts dragging their chains behind them.”

For his part, Pétain spoke only at the beginning of the trial but maintained a vow of silence for most of the proceedings. The old general’s solemnity was interrupted only by the occasional outburst and the tapping of his cane. Although some of his advocates would later argue senility, and the marshal himself would sometimes pretend to be deaf, Jackson shows that Pétain was keenly aware of what was going on. His health remained robust, and his ego undiminished.

Pétain’s rise and fall from grace were far from preordained. Before World War I, he had a largely undistinguished military career, his rise in the ranks hampered by a skepticism of the prevailing French military doctrine, which emphasized offensive actions. Appropriately enough, it would be the Battle of Verdun, one of history’s most celebrated defensive engagements, that would make him famous. Pétain would be elevated to “Marshal of France,” a military distinction awarded to generals for exceptional achievement. His wartime experiences, including his handling of the 1917 French army mutinies, left him with a distrust for democracy, a belief in the importance of order, and, most importantly, confidence that he was a man of destiny. His exaggerated sense of self-importance never deserted him.

Pétain and his supporters would later invent a litany of excuses to justify the old general’s decision to work with the Nazi regime. Pétain would later claim that his handshake with Hitler wasn’t even a proper handshake, telling an attorney, “But I only took his fingers.”

Pétain argued that he served as a “shield,” preventing France and its people from being victimized to the full extent, as the Nazis did in other countries, such as Poland or the Netherlands. The worst excesses of the Nazi regime, the marshal and his advocates claimed, had been prevented or diminished.

Some of Pétain’s supporters would even argue that the creation of Vichy helped lead to an Allied victory, preventing Francophone Africa from falling into Nazi hands. Yet Vichy forces did, at times, attack Allied troops. And by actively collaborating, Vichy France freed up Nazi forces to be used elsewhere. At times, Vichy police were even “essential,” Jackson notes, “because the Gestapo headquarters in Berlin had just warned their representatives in Paris that they could not provide any more manpower.”

Indeed, as Jackson and other historians have highlighted, there were several moments when Pétain could have fled to North Africa or resigned. But he “opted instead to remain in place, linking his fate irrevocably to the Vichy regime until its demise in August 1944.” It was, Jackson notes, a fateful decision, as the last months of Vichy witnessed some of the worst atrocities of the Occupation. Pétain’s presence “only served to disguise ever more repressive German policies.” As his critics would note at his trial, “the gift” of Petain’s person helped shield the evils perpetrated under his name.

“The trial of Pétain,” Jackson observes, “was in some sense putting France on trial: Few people had not at some moment believed in him. He may have been a sacrificial victim in the national catharsis of the Liberation, but complicity in the actions of his regime was widely shared.”

The exact nature of Pétain’s crimes was disputed, then and now. His former protege-turned-nemesis, Charles De Gaulle, argued that the armistice itself was a crime. Clean hands were a rarity. In fact, as Jackson notes, several of the prosecutors and figures involved in the Pétain trial had worked, albeit often in minor roles, in the Vichy apparatus.

As Jackson highlights, some of Vichy’s chief victims, Jews, were given little attention at the trial. Vichy’s role in the deportation of 75,000 Jews and its avowed antisemitism weren’t foremost on the minds of those prosecuting Pétain and other collaborators. Pétain and his defenders would make the ghastly argument that they sought to protect French Jews by sacrificing foreign ones. They claimed that French Jews had a higher survival rate than those of other Occupied countries in Western Europe thanks to Pétain and his “shield.” Yet, as Jackson and others have argued, this can be explained, in part, by France’s geography — its hills and mountains and borders with neutral Switzerland and Spain giving them shelter. And revisionism notwithstanding, Pétain approved of many of Vichy’s worst crimes.

The diaries of Paul Baudouin, a Vichy foreign minister, recorded a 1940 meeting in which Pétain pushed to make the Statut des Juifs even harsher. Pétain’s handmade annotations argued that magistrates and teachers should be added to the list of professions from which Jews would be excluded. Vichy would also voluntarily propose to arrest Jews in parts of France that were supposedly independent and “out of German reach.”

France itself was slow to reckon with Vichy’s antisemitism. It was only in 1997 that the Paris Bar, the French Catholic episcopate, and the Order of Doctors offered apologies for their complicity. And it was only then, more than half a century after Pétain’s trial, that the government set up a commission to investigate the deportation of French Jews and offer them compensation.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Beginning in 1968 with De Gaulle, every French president has laid a wreath on Pétain’s tomb on the anniversary of the World War I armistice, a practice that lasted until 1992. Jackson also ably documents the bizarre cult of Pétain supporters, whose fondness for Vichy and the marshal remains undiminished by the growing body of evidence of his crimes. Indeed, as the historian suggests, it is precisely because of these crimes and what Pétain represents that he has continued to maintain a vocal, if small, group of defenders.

After Pétain’s conviction, the novelist François Mauriac observed, “A trial like this one is never over and will never end.”

Sean Durns is a Senior Research Analyst for CAMERA, the 65,000-member, Boston-based Committee for Accuracy in Middle East Reporting and Analysis.