The O.C. premiered 20 years ago. Was it the beginning of an era of TV or the end of one?

Derek Robertson

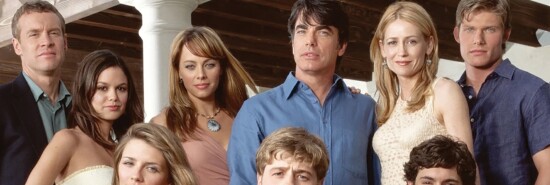

The pilot episode of The O.C., which aired 20 years ago Aug. 5 — tick tock, fellow millennials — begins in uncommonly cinematic style for a network soap opera. Filmed with a grainy sheen that recalls The Taking of Pelham One Two Three more than something meant to compete in the American Idol time slot, the opening scene of the premiere introduces America to Ryan Atwood (Ben McKenzie), a baby-faced hoodlum from California’s Inland Empire who finds himself behind bars after a car theft gone awry. When a do-gooding public defender (the indomitable Peter Gallagher) decides to take him into his Newport Beach mansion (long story), an expertly tuned machine for producing televised melodrama kicks into gear.

The show at its best is a quintessential fish-out-of-water parable, with all the implicit, sexy contrasts in economic, social, and moral status. In that premiere, the contrasting elements that propelled the show to its brief, glorious run at the summit of American monoculture are all visible: an auteur’s touch but with the unmistakably pitched narrative trappings of the telenovela; gorgeous, scantily clad young actors planted with two feet in adult social drama; and fealty to W.-era youth culture that carbon-dates the show but still bears the unmistakable imprint of John Hughes’s and Cameron Crowe’s 1980s youth culture.

BLACK MIRROR IS BACK WITH A SIXTH SEASON TO MAKE US WONDER IF WE ARE BUILDING A HORROR FUTURE

That was almost entirely due to one man, the show’s creator, Josh Schwartz, who was only 26 years old when the show first aired, then unthinkable in the ossified world of TV writing. Much of the initial press around the show focused not on its cast of starlets or the nascent 2000s indie rock culture it introduced to the mainstream but on Schwartz and the uncommon level of personal control he exerted over the show. One Fox executive cooed to the New York Times in 2004 that “it’s all to service Josh’s vision. This show is his baby.” Looking back on The O.C. today, one realizes that Schwartz both perfected and completely broke the highly serialized factory-line model of network TV production. His creation endures as a humane, self-aware, genuinely exciting soap that an entire generation would eventually fail miserably to replicate, or lose interest in doing so entirely.

And The O.C. was, despite its auteurist trappings, above all else, great TV qua TV. Everything from its revolving door of beautiful people to the cocaine-chic SoCal milieu to the perfectly schlocky dialogue — “Welcome to the O.C., bitch!” — is done in service of reaching as wide an audience as possible and keeping them hopelessly on the hook as to what will happen next week. As many of the show’s chroniclers have pointed out, one of its most intelligent gambits was to widen its potential audience by keeping an equal narrative focus on the stellar adult cast, as the sordidness of their world of affairs and white-collar crime frequently surpasses the teenagers’.

Special tribute must be paid here to the center of that cast of grown-ups: Gallagher’s crusading, winningly boyish public defender, Sandy Cohen. The fictional Cohen was, arguably, the last great standard-bearer for one of the medium’s most essential elements: the TV dad. Omnipotently empathetic, ready with an easy smile and wisecrack, but willing to flash his industrial-strength eyebrows in righteous anger at a moment’s notice, Gallagher as Cohen perfectly embodies the idealized father figure one might want to invite into their home week after week. His benevolent paternalism invites a corny but deep and true nostalgia — they don’t make them like this anymore.

It feels a little bit silly to wax nostalgic about something so inherently ephemeral and to compare today’s own trivial entertainments to it so unfavorably. But that ephemerality was its greatest strength. As wonderfully entertaining as The O.C. still is, it’s ultimately “just TV” — and it’s almost impossible to imagine something so comfortable with its own limitations becoming an equivalent phenomenon now. Consider the apocalyptically dull, abstracted conversations about youth sex and drug use that surround HBO’s Euphoria or about Ted Lasso and mental health. The O.C. introduced a generation of suburban teenagers to The Shins and Belle & Sebastian; it midwifed modern internet fandom; it inculcated a generation with its creator’s hand-me-down 1980s pop culture obsessions.

One doesn’t have to surrender fully to that nostalgia to notice upon revisiting The O.C. in 2023 that there’s a key differentiating element to the show that seems to have totally evaporated from today’s television, if not culture writ large. Despite the occasionally arch, screwball dialogue, metafictional winks at the format itself, and co-star Adam Brody’s ironic TV-PG Woody Allen schtick as Cohen’s son, the show is painfully sincere. What series like Euphoria (or even, for the most part, Schwartz’s own successor project, Gossip Girl) fail to understand is that melodramatic shock antics only register emotionally if the audience who witnesses them has been prompted to understand and accept the characters’ humanity.

The best example of this from The O.C.’s first season is from the fan-favorite episode “The Escape,” in which a furtive trip down to Tijuana ends with the protagonist Ryan carrying his troubled girlfriend Marissa in his arms through the rain to save her from a near-fatal overdose. It’s played at an operatic pitch that strains credulity. But it never breaks because nothing in the show instructs the viewer to view these people with derision or moral judgment, as it likely would if it were produced today. The other side of this coin is that the show’s more understated dramatic beats can be quite jarring. When Luke, Ryan’s Ken-doll-like frenemy, stumbles upon his father in a homosexual tryst midway through the show’s first season, the lack of prurience with which it’s treated is almost shocking. It’s just sad and embarrassing for everyone involved.

In a society where moral and social standards are largely set by mass media, “good television” tends to make you think of its characters as you would your neighbor. The O.C. walked an astonishing high-wire act, depicting an utterly fantastical world of sordid rich-person antics with a humanist flair, like Beverly Hills, 90210 before it (but much, much better). It bonded a generation to Ryan and Marissa and Adam and Summer as if they were real friends.

Until it didn’t. Notoriously, as the show’s runaway success conjured the familiar backstage demons of dueling egos (and financial demands) among the cast, the show’s creative team decided to kill off Mischa Barton’s Marissa in its season three finale, indisputably its last relevant cultural moment.

Schwartz expresses ambivalence about the narrative choice to this day, telling MTV in 2016 that “there were a lot of reasons, both creative and cynical. … People were very attached to that character. There was a lot of anger and fan art that came our way.” Barton would in 2021 tell E! News that on-set “bullying” and the pressures of the network production schedule drove her off the show. But whatever the real reasoning, the dramatic death and the show’s subsequent decline were, appropriately enough for a soap opera, fated. The O.C. was not prestige television and was all the better for it, creating warm but light bonds of parasocial “friendship” with its cast while placing them in increasingly absurd narrative scenarios. The shark was always lurking in the water. It was just a question of when Schwartz and his crew would jump.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Derek Robertson co-authors Politico’s Digital Future Daily newsletter and is a contributor to Politico Magazine.