Accommodations for dictators: New books look at Stalin’s hotel and Hitler’s brothel

Malcolm Forbes

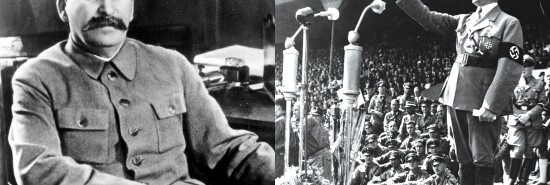

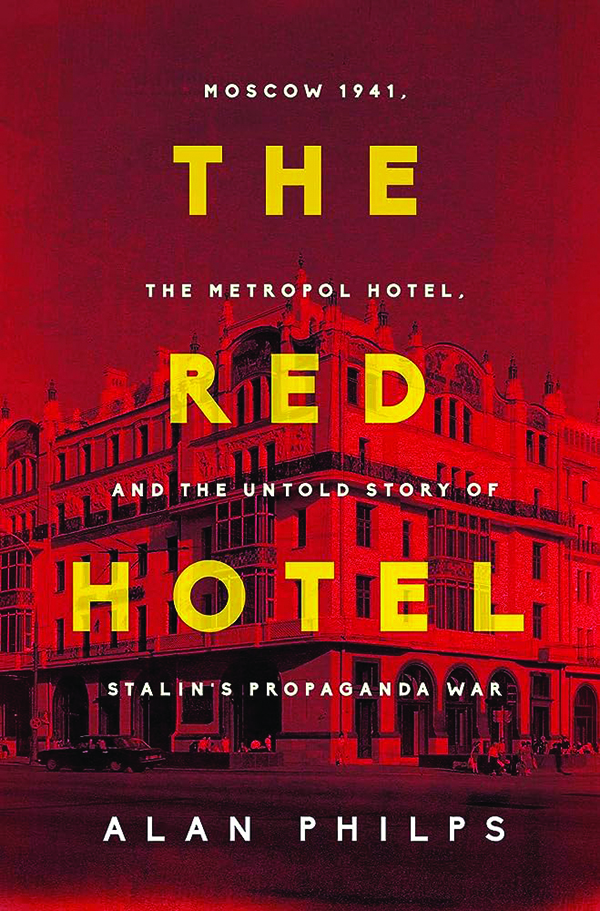

Since it opened its doors in 1905, the Metropol Hotel in Moscow has witnessed seismic events in Russia’s 20th-century history. In its early years it was a glittering playground for wealthy merchants, louche cavalry officers, and ladies of leisure and luxury. When the Bolsheviks seized power, Tsarist officers beat a retreat to the hotel to fight a last losing battle against the revolutionaries. Afterward, Lenin requisitioned it, renamed it the Second House of Soviets, and sent from it the telegram instructing the massacre of the deposed Tsar Nicholas and his family. The building became a hotel again under Stalin, but during his Great Purge not all residents made it through the night. Guests slept more soundly after the dictator’s death, and in 1991 some of them included exiles who enjoyed a celebratory dinner at the hotel to mark the thawing of the Cold War and the bitter end of Communist Party rule.

During World War II, the Metropol provided a base for a different type of guest: British, American, and Australian reporters. Foreign journalists had not been welcome in Russia prior to the outbreak of hostilities. In the country’s bid to transform itself into an industrial power, its people were dying of famine. The Kremlin tried to hide this inconvenient side effect from the outside world by making working conditions difficult for reporters. By the end of the 1930s, most had admitted defeat and left. But when Germany invaded in 1941, the situation changed.

PHILOSOPHY’S HISTORY, HANDSOMELY BOUND AND SMARTLY WRITTEN

Winston Churchill, who himself had been a war correspondent in his youth, lobbied Stalin to permit entry for an Allied press corps to cover the battles being waged on the Eastern Front. Churchill believed that eyewitness accounts of the conflicts would convince the British public of the need to send tanks and aircraft to the beleaguered Red Army. Desperate for such supplies and painfully aware that German forces were advancing on Moscow, Stalin consented, and then implemented measures to ensure the journalists danced to his tune.

British author Alan Philps’s The Red Hotel shines a light on the men and women caught up in Stalin’s propaganda machine and their attempts to tell the truth in a foreign land during a pivotal stage of the war. Philps, formerly a Moscow correspondent for Reuters, explains at the outset that as he researched the book, he learned of the key role played by the female Soviet secretary-translators who aided the visiting journalists. Philps gives them equal billing and shows the lengths they went to and the risks they took to reveal what life was truly like in Stalin’s Russia.

It was certainly a different world at the Metropol. Philps paints a picture of stark contrasts: As Muscovites shivered and subsisted on meager rations, the journalists were kept sweet with hot water in en suite bathrooms and steady supplies of caviar, cream pastries, and vodka. They had everything they needed, writes Philps, “except the freedom to write a genuine news story.”

Stalin’s restrictions ran the full gamut, from wholesale censorship to prohibited contact with Soviet citizens to banned visits to the battlefront. The hotel became a “gilded cage” for the increasingly frustrated reporters who had nowhere to go and little material to work from other than sanitized reports from the Soviet press. On the rare occasions when a select few correspondents were granted permission by the Press Department to go on trips to see the Red Army in action, they got nowhere near the front, or they were taken to long deserted battlefields or shown stage-managed scenes of happy, healthy, and hospitable Soviet troops.

Philps’s book is at its most engaging when he focuses on the journalists individually rather than en masse. Some are classed as “Kremlin stooges”; those that deviated from the party line and sought to speak out against the man of steel’s iron grip on his nation were, in Soviet parlance, “fascist beasts.” The former category includes Ralph Parker, the Moscow correspondent for the Times, who also moonlighted as a British spy, but was in fact a double agent, working for the NKVD. The latter category comprised the English eccentric Ronald Matthews who, along with his secretary-translator (and later wife) Tanya Svetlova, “fought a quixotic and sometimes farcical rear-guard action against official propaganda, a struggle which at moments of crisis led to fists flying in the press room.”

Some character profiles stand out. One is of wealthy American socialite Alice Moats, who traveled alone to Russia without a press card, secured a job with Collier’s despite having no journalistic training, and proved to be tough, brave, and resourceful in her quest to discover the fate of hundreds of thousands of Poles that were victims of Stalin and Hitler’s depredations. “I am doing a man’s job and willing to take a man’s chances,” she declared. There is also the English writer and reporter Charlotte Haldane, who arrived in Russia as a committed communist but, after glimpsing horrors and experiencing injustice, left thoroughly disenchanted with Stalinism.

Haldane wasn’t the only woman to renounce her beliefs. Philps devotes the bulk of the book to the remarkable, indomitable Nadya Ulanovskaya, and charts her journey from teenage revolutionary to skilled spy to secretary for the Australian reporter Godfrey Blunden. Ulanovskaya eventually had her fill of the Soviet version of reality and opened Blunden’s eyes to the true state of affairs. But when he went on to write a novel based on Ulanovskaya’s revelations, she was sentenced to 15 years in the Gulag.

Ulanovskaya’s tale makes for compelling reading, but also disjointed reading, as Philps tells it in installments throughout his multistranded narrative. In addition, many of these chapters, particularly Ulanovskaya’s daring prewar exploits and her ordeal in the labor camp, take place far from the Metropol and have nothing to do with the journalists and Soviet media control. Her story deserves to be told in full elsewhere. Philps’s episodic rendering of it mars what is an otherwise clearsighted and riveting study of those who checked into a hotel in Moscow and found themselves at “the heart of Stalin’s wartime disinformation campaign.”

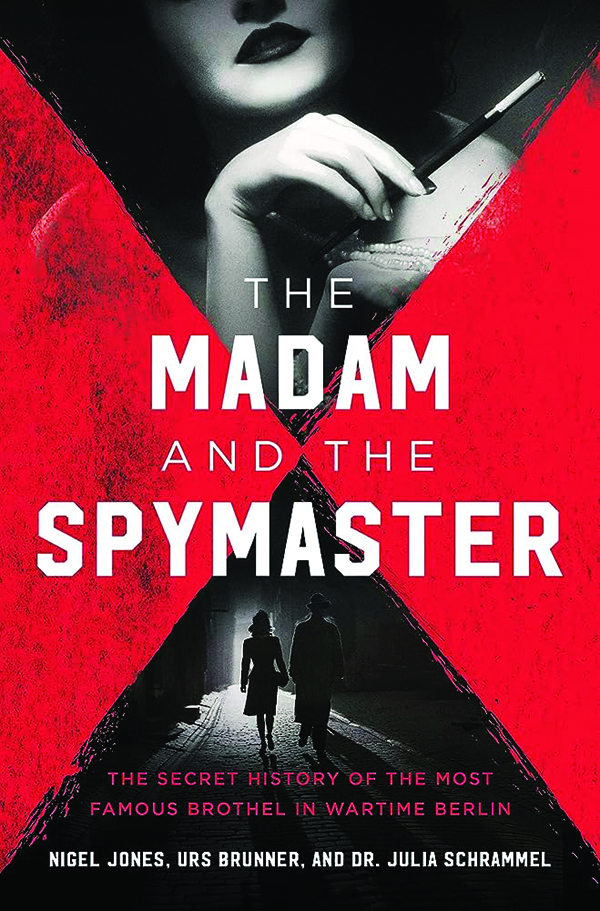

Another new book revolves around a different kind of building used for a different manipulative purpose during the war by a different totalitarian regime. The Madam and the Spymaster comes billed as another untold story, supposedly one of the last of the Third Reich. Journalists Nigel Jones, Urs Brunner, and Julia Schrammel attempt to debunk the myths and piece together the facts about a Berlin brothel owner and the Nazis’ conversion of her exclusive establishment into an “espionage center,” one in which the walls had ears.

The authors chronicle the personal history of the woman behind Salon Kitty. Katchen “Kitty” Emma Sophie Schmidt was born in Hamburg in 1882. At the age of 26 she moved to Britain and worked as a governess and piano teacher. She was married briefly to a Spaniard who later committed suicide, leaving her with a young daughter. At the end of World War I, she returned with her child to her native land and opened her first “salon” in Berlin.

In 1935, after making her mark and securing a reputation as a well-known, well-dressed woman about town, Kitty opened her second brothel. Salon Kitty became a luxurious, high-society bordello that catered to both German VIPs and distinguished foreign visitors. Then just before the outbreak of World War II, the Nazis made Kitty an offer she couldn’t refuse.

Or so it is claimed. The authors draw on some dubious sources: the self-seeking postwar memoirs of SS functionary Walter Schellenberg, throughout which he is “tantalizingly elusive, and typically sparse with concrete information about the spy brothel”; and the book Madam Kitty by the journalist Joseph Fritz (writing as Peter Norden), who called his work a “documentary novel,” a blend of fact and fiction which the authors describe as “riddled with half-truths.”

For the most part, the authors are on firm ground with their potted biography of Kitty, although their lack of primary source material only allows them to present “an accurate sketch” and not “a fully documented account” of her life. Problems arise when the Nazis arrive on the scene. The book argues that it was “Hitler’s hangman” Reinhard Heydrich who devised the idea of transforming Salon Kitty into a listening post, with microphones in the “love rooms,” technicians in the cellar, and a team of specially trained prostitutes tasked with extracting secrets from their clients in pillow talk. But it is unclear what “Madam Kitty” thought of this scheme. One version of events casts her as an opportunist who willingly cooperated with the Nazis. Another depicts her as a victim who was brutally coerced into supporting Heydrich’s plan.

The authors hedge their bets by summing her up as an “intelligent survival artist in times of extreme chaos and violence.” It is heartening to learn that there are reports that she helped Jews escape Nazi persecution, and may even have given one a job — and by extension, shelter — in her kitchen.

But all too often, the authors’ inquiries hit dead ends, leading them to swap facts for speculation. They try to construct something substantial from “scant and contradictory” evidence or “murky and mysterious” details, and are forced to sift stories that originated, and mutated, from “the unverifiable miasma of post-war rumor.”

The story of Kitty and “Berlin’s most infamous bordello” comprises only part of the book. The rest is made up of very loosely linked topics: the decadence of Weimar Berlin; the stamping out of sexual freedoms under the Nazi jackboot; the “human stud farms” at the heart of the Nazis’ Lebensborn program; the brothels for guards and inmates in concentration camps; and the sex lives of Nazi top brass, from SS chief Heinrich Himmler (memorably described as a “bespectacled, chinless failed chicken farmer”) to the fuhrer himself. The authors argue that these sections provide crucial context. While fascinating, they feel tacked on to pad out, and ultimately render the book’s title a misnomer.

The Madam and the Spymaster tells too little of one story; The Red Hotel tells too much of another. But both books ably demonstrate how during the war, two dictatorships used words, either artfully written or carelessly spoken, to keep a stranglehold on power.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Malcolm Forbes has written for the Economist, the Wall Street Journal, and the Washington Post. He lives in Edinburgh.