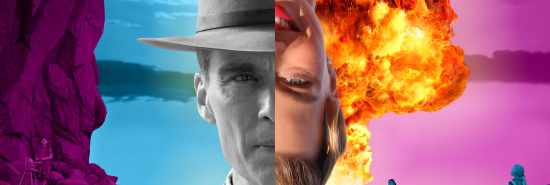

The atom splits, the genders unite, and the block busts

Derek Robertson

Last weekend’s twin cinematic debuts of Greta Gerwig’s Barbie and Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer didn’t just comprise a cultural event but also an economic one — the films combined to gross somewhere around $235 million, powering the domestic box office to only its fourth-ever $300-million-plus weekend.

So, hooray for cinephiles, Warner Bros., Universal Pictures, and theater exhibitors across the country. But… how did this happen? Why did what on the surface appears to have been a classic bit of studio counter-programming — maximizing a film’s audience by releasing it at a time when its main competition has almost zero demographic overlap — turn into a culturewide, borderline historically significant phenomenon?

WHY MISSION: IMPOSSIBLE THRIVES WHILE BOND AND INDIANA JONES WITHER

As with so many elements of modern culture, you can mostly blame it on the memes. The ever-so-perceptive Twitter hive mind, picking up on the fact that these two movies are, in fact, quite different, plastered the internet with “Barbenheimer” jokes, debating everything from the order in which the two films should be double-featured to the ideal culinary (or narcotic) accompaniments for each.

This was all accompanied by an implicit, unseemly gender essentialism: Gerwig’s Day-Glo, girl-powered feminist update on the Barbie mythos (to the extent that it exists) was for the girls, Nolan’s typically dour, Wagnerian opus about the American conscience (or lack thereof) for the boys. Thankfully, despite the insufferably unfunny fever pitch this discourse reached on social media, each film resists and confounds those expectations in a way that gives the viewer a modest amount of hope for the future of blockbuster cinema and tells its own, less reductive story about duality in American life.

Let’s start with Barbie. Predictably, the film carried the brunt of the box office weight with a $160-million-plus haul — a doll beloved by generations (not to mention Margot Robbie) being a bit of an easier sell to the public than a heady meditation on the development of the atomic bomb.

Equally predictably, the film has already become something of a culture-war football, with conservative commentators such as Ben Shapiro gnashing their teeth at the cultural dominance of a film that dares to mention the concept of “patriarchy.” But if the film’s conservative critics could push through their initial discomfort at the film’s perfunctory nods to an already-passe-feeling, 2010s-era lifestyle feminism, they’d discover a film that’s much more self-aware about, and even generous to, men than they would expect. The script by Gerwig, the creative mind responsible for the Oscar-nominated Lady Bird and Little Women, and her fellow-director husband Noah Baumbach (Marriage Story, The Squid and the Whale) cleverly asks the all-too-relevant question of what the world looks like when people substitute stock gender roles for actual personality or introspection.

The crux of the film is a takeover of “Barbieland” by Barbie’s longtime beau Ken, played by a sublimely goofy, movie-stealing Ryan Gosling. After a furtive trip to the “real world,” where Ken realizes that men actually have, you know, power, instead of just serving as eye-candy beach ornaments, he imports those values back to Barbie’s realm, declaring it the “Kendom” and enlisting Barbies who were once presidents or neurosurgeons as beer-fetching handmaidens.

Without belaboring the plot of a film largely intended for 10-year-olds, after a series of impassioned monologues about selfhood, creaky jokes about men “mansplaining” The Godfather, and an improbably hilarious Gosling-led musical number, balance is restored to Barbieland when Robbie’s charmingly naive human doll patiently explains to Ken that maybe they should each develop their own personality and role in life independent of, but complementary to, one another. It’s mawkish, but sweet, simple, and truly refreshing in a cultural climate otherwise all too eager to smother the individual under the pillow of group identity. Gerwig and Baumbach are too clever and human for all that; the fact that their writerly intelligence and perspective made it through the studio gantlet to result in this unexpectedly subversive film is a testament to its power.

Then, there’s Oppenheimer. The film is an adaptation by Nolan of Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin’s American Prometheus, the biography of Manhattan Project director and theoretical physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer. Featuring a blistering performance from Cillian Murphy as Oppenheimer, the film deploys all of Nolan’s cinematic signatures, from its bombastic Ludwig Goransson score to its elliptical, rug-pulling narrative structure, to an astonishing level of visual detail and intensity.

It is, in a word, wonderful, second only in Nolan’s filmography to 2017’s Dunkirk, one of the greatest war films ever made. The sheer volume of information and narrative action elegantly packed into its 180-minute run time should earn Nolan an Oscar nomination for its screenplay, in addition to the inevitable nods for directing and Best Picture. Nolan accomplishes this through a narrative gambit that’s baffled some critics, framing the story of the Manhattan Project with the years-later Senate confirmation hearings of Lewis Strauss (Robert Downey Jr.) as Eisenhower’s secretary of commerce. But rather than bog the film down in Oliver Stone-like melodrama or grandstanding, Strauss’s indirect clash with Oppenheimer reveals the film’s true message about the irrelevance of human ambition.

Throughout the film, Nolan centers the Sphinx-like visage of Murphy’s Oppenheimer as it changes in response to a meeting with Niels Bohr (a jolly Kenneth Branagh), his ill-fated affair with the communist writer Jean Tatlock (Florence Pugh), and, yes, the Trinity test itself, rendered here with an audio-visual impact that, lord willing, will be as close as any of the film’s viewers ever get to the real thing. Murphy gives the film, no pun intended, its spark. When he’s onscreen, you’re not wondering what will happen next (there aren’t exactly any spoilers to this story) but what he’ll feel about it, whether he sees himself as an instrument of history or its driver as he unleashes the deadliest weapon known to man. Which is, of course, the film’s point: He’s both, and neither.

Lewis Strauss hated Oppenheimer for his glib, elitist showboating and went to absurd lengths to destroy his reputation as such; Oppenheimer believed these social concerns beneath his consideration as a high priest of the sciences. But both men’s ambitions are destroyed, as Strauss’s underhanded defamatory tactics cost him his Cabinet position and Oppenheimer finds himself helpless, as he always was, to stop his scientific discovery from powering the specieswide human sacrifice ritual that is the nuclear arms race. Oppenheimer, the genius, the American Prometheus, was both instrumental and completely irrelevant to this process. All of the crystalline introspection Murphy communicates is for naught, with one of the film’s final, haunting images being a glassy-eyed Oppenheimer near the end of his life receiving honors at the White House with a look of numb neutrality, as much a cog as his now-forgotten opposite number Strauss.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

And for as little as Barbie and Oppenheimer have in common, they do overlap here. Ultimately, both films are explorations of that stubbornly American obsession, the self. For Barbie and her compatriots, the self is something to be discovered, cherished, nurtured to its full bloom. A healthy society is one of fully realized selves, acting in harmonious, loving self-interest. Oppenheimer shows us the dark mirror image of that society, where for all the titular scientist’s introspection and innovation, he is ultimately subordinate to those who, Machiavelli-like, gratify themselves via actual power — that is, the United States Army and military-industrial complex, befitting Nolan’s typically grim, Hobbesian worldview.

Put more simply, for Oppenheimer, “being himself” meant quite literally bringing humanity to the brink of destruction. Beyond idiotic gender stereotypes, cloying internet fan culture, or cineaste boosterism, to pair these two films is to be reminded of the empowering spark of individual conscience and personality, and what might happen when it’s pursued to its logical conclusion. From the mouth of Shakespeare’s Polonius, “to thine own self be true” isn’t a feel-good coffee-mug slogan but the gloating exhortation of a pompous windbag. Maybe this cinematic double shot will, if nothing else, remind its viewers of just how malleable those selves can be.

Derek Robertson co-authors Politico’s Digital Future Daily newsletter and is a contributor to Politico Magazine.