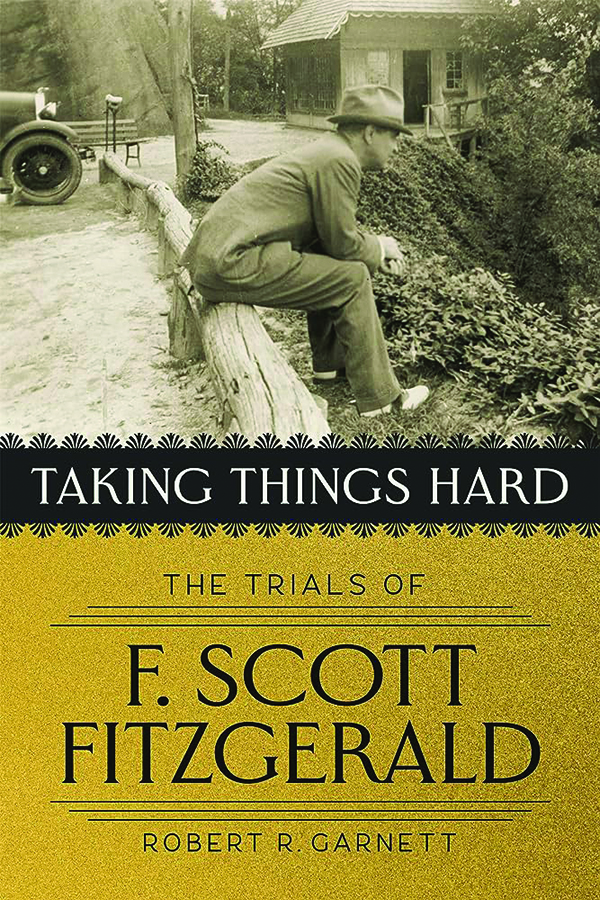

Review of Taking Things Hard: The Trials of F. Scott Fitzgerald by Robert Garnett

Diane Scharper

F. Scott Fitzgerald was 28 years old and at the height of his career when he wrote America’s favorite novel, The Great Gatsby. Shortly thereafter, his fortunes began a decline ending with his death from heart disease at age 44.

His death was most likely brought on by his dissolute lifestyle, his stress over his wife’s schizophrenia, financial problems, and alcohol abuse. It didn’t help that the stock market crashed in 1929, ending the Jazz Age and causing the Great Depression.

A NEW HISTORY REVEALS OUR DEBT TO 1848’S REVOLUTIONARY ERA

That’s the trajectory of Robert Garnett’s latest biography, Taking Things Hard: The Trials of F. Scott Fitzgerald, which showcases the second half of Fitzgerald’s life when the bright flame of his promise began flickering out.

A retired professor of English at Gettysburg College, Garnett is best known for his biography of Charles Dickens. Taking Things Hard is engaging but less intimate, offering a workmanlike take on Fitzgerald’s last 20 years. Garnett tends to leave out occurrences that add texture to Fitzgerald’s character — as opposed to Matthew Bruccoli in his definitive biography, Some Sort of Epic Grandeur.

For instance, Garnett’s title comes from a letter that Fitzgerald wrote two years before his death. Advising a young woman about her work, he tells her to take things hard. He says he “dragged The Great Gatsby out of the pit of my stomach in a time of misery.” Yet, Garnett offers little evidence for Fitzgerald’s misery while he was writing Gatsby. Fitzgerald’s hard times seemed to come later.

This biography includes excerpts from Fitzgerald’s letters, stories, and novels and uses Fitzgerald’s ledger, which he kept as a scaffolding for his life. But Garnett seldom gets inside Fitzgerald’s psyche.

Garnett, though, has an ear for the apt quote mentioning the journal of Fitzgerald’s secretary, Laura Guthrie, who is irritated with Fitzgerald when he asks her to bear with him because of his condition. Guthrie writes, “What kind of condition do you think I am in! Dealing day and night with a practically crazy drunk. And trying to complete a story sensibly meanwhile.”

Francis Scott Key Fitzgerald (1896-1940) published four novels, four story collections, and 164 short stories in his brief life. Fitzgerald’s work was popular in the 1920s but then fell out of favor. He is now regarded as one of America’s greatest writers partly because of Gatsby’s popularity. His work focuses on the decadence and excess of the roaring twenties and the Jazz Age. He used the term to mean sex, music, and dance, individually and in combination. In a sense, jazz is also the theme of his life and the cause of his demise.

Related to Francis Scott Key, Fitzgerald had roots in Maryland, lived in New York for several years, but spent most of his growing-up years in St. Paul, Minnesota. He started writing stories and poems in elementary school. His creative work first appeared in print at 14 with a short story in the St. Paul Academy literary journal.

Later, at the Newman School for Boys in Hackensack, New Jersey, he wrote several poems and stories published in the student literary journal. When these came to the attention of the headmaster, Monsignor Cyril Sigourney Fay, Fay became a mentor to Fitzgerald, keeping in contact with the writer during his early years at Princeton, which he entered in 1913. Because of his poor grades, excessive drinking, and partying, Fitzgerald failed out of Princeton and joined the Army. When he was stationed at Fort Sheridan in Montgomery, Alabama, he met Zelda Sayre, whom he later married.

After Fay died of pneumonia, Fitzgerald was devastated and considered becoming a priest. He recreated Fay in the character of Monsignor D’Arcy from This Side of Paradise and dedicated the book to Fay. One of Fitzgerald’s admired short stories, “Benediction,” suggests Fitzgerald’s conflicts regarding the priesthood and religion. Unfortunately, Garnett doesn’t discuss that story. He also omits any description of Fitzgerald’s on-and-off affiliation with his Roman Catholic faith.

Fitzgerald was 23 when Scribner’s Sons published his first novel, This Side of Paradise. When he was 26, The Beautiful and the Damned came out. When he was 28, The Great Gatsby was published. Then, with the exception of a mixed bag of short stories, he produced almost nothing for nine years.

Fitzgerald wrote stories for fast money and published them mostly in magazines such as The Saturday Evening Post. Fitzgerald generally had little regard for most of his short stories, making Garnett’s discussions of them seem overly long. This is especially true of Garnett’s treatment of “The Darkest Hour,” one of Fitzgerald’s least popular stories.

Fitzgerald had been hoping for a life of leisure after Gatsby. Counting on royalties from the novel, he and Zelda had left Long Island and moved to France, ready for the sands of the Riviera with friends such as Ring Lardner, James Joyce, T.S. Eliot, and Ernest Hemingway.

But sales from the novel were modest, and after working four years on the manuscript for his fourth novel, Tender Is the Night, Fitzgerald was vexed. He took the seventh draft out on a rowboat and “tore it up page by page,” flinging it into the Mediterranean Sea.

When Tender Is the Night was finally published in 1934, it garnered mixed reviews. His final novel, The Last Tycoon, wasn’t a novel so much as notes for a novel put together by his friends after his death and published in 1941. Although he tried, he was never able to match the brilliance of Gatsby.

In his last years, Fitzgerald worked as a Hollywood writer for MGM but was let go. Then he did freelance work. He wrote fatherly letters to his daughter, Scottie. The gossip columnist Sheilah Graham became his paramour. He was drinking, and his writing wasn’t going well. He died of occlusive arteriosclerosis on Dec. 21, 1940, with 44,000 words of his final novel written.

According to Garnett, Fitzgerald’s and Zelda’s marriage was toxic early on. Before he met Zelda, he had been in love with the wealthy and beautiful Ginevra King, who jilted him. Depressed, he met and too quickly became involved in a rebound relationship with Zelda, who didn’t want to marry him until he was rich and famous.

Although Zelda was Fitzgerald’s muse, she was also a distraction and an irritant, the grain of sand in his oyster. Their lives revolved around socializing and drinking. She had an affair with a French aviator. He had an affair with a 17-year-old actress.

Hemingway believed Zelda was in competition with Fitzgerald, and the two should have never married. Some said that his drinking caused Zelda’s breakdowns. Others said that Zelda’s breakdowns caused Fitzgerald to drink. Ultimately, as Garnett depicts it, there was enough negativity to ruin both of their lives.

And it did.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Diane Scharper is a poet and critic. She teaches the Memoir Seminar for the Johns Hopkins University Osher Program.