At the corner of airport spy novel and great literature

Gustav Jönsson

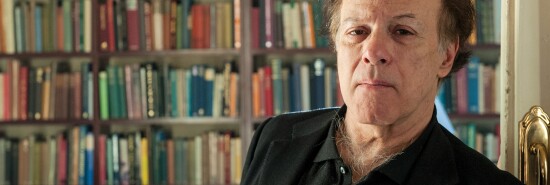

“I do like to observe the tropes,” says Bertram Tupra, the irascible British Secret Service handler in Javier Marías’s new novel Tomás Nevinson, and so does Marías. The plot of his final novel — he died aged 70 last autumn — is the stuff of potboilers. Tomás Nevinson, a retired MI6 agent, works for the British Embassy in Madrid when Tupra offers to bring him back “inside” for “one last assignment.” Nevinson is to travel to “Ruan,” a self-regarding town in northwest Spain, in order to identify an IRA member on long-term loan to the Basque separatists of the ETA.

Magdalena Orue, or Maddy O’Dea, is half-Northern Irish, half-Spanish; she’s implicated in two fatal bombings in 1987 but has always remained in the shadows. Now, 10 years later, Spanish intelligence has tracked her to Ruan, where she lives under an assumed name. Tupra has been asked by his Spanish “friend” Machimbarrena to take care of the matter “extra-officially.” So, he gives Nevinson pictures of three seemingly innocent women: O’Dea is one of them. It is Nevinson’s job to find out which of the three she is and, if necessary, eliminate her. Pretending to be an English teacher by the name of “Miguel Centurion,” he soon inveigles himself into their lives: as a lover, a colleague, and a friend. Struggling to find proof, he must identify O’Dea before time runs out.

WHAT HARRY TRUMAN DIDN’T KNOW ABOUT THE NUCLEAR BOMB

As I said, the spy tropes are certainly observed. Machimbarrena’s people have planted cameras and microphones in the living rooms of Maria Viana and Celia Bayo, but not in the flat of the third suspect, Ines Marzan. Fortunately, Nevinson’s flat faces hers, so he can spy on her with binoculars. “Just like in Hitchcock,” I note, only to turn the page and read Nevinson reflect: “I couldn’t help but feel that I was imitating James Stewart in Rear Window.” And in this, as in every spy story, we’re repeatedly told that it’s operatives like Nevinson and Tupra who hold the world together and that civilians sleep safely only because the secret services they criticize watch over them at night. It is the kind of spiel M gives Bond when he’s sent out with license to kill.

As much as Tomás Nevinson is a thriller, it’s a comedy of manners of provincial Spanish life. Marías gives his side characters a marvelous Dickensian vividity. There’s the society columnist Florentín, a local celebrity of sorts, who’s cultivated a Faginesque style, replete with an ankle-length overcoat. He is well read, and proud of it. His literary pseudonyms, each more ridiculous than the next, include “Champfleury” and “Louvet de Couvray.” And there’s the petty cocaine peddler Comendador, who, in spite of his name, is a total pushover. Comendador sports 1960s-style sideburns but otherwise looks as though he were straight out of a Western, wearing a waistcoat, leather trousers, and pointy boots. Perhaps the most colorful character, the loutish fraudster Liudwino, is precisely the kind of human gargoyle one might find in a provincial town: “Today, I finally got Gausi to kiss arse,” he boasts, “and as for Valderas, I’ve got him on such a tight lead, I can take him anywhere I want, it’s amazing how quickly I broke him in.”

None of the three suspects have the same weight on the page as Comendador or Florentín. For instance, Celia Bayo, Liudwino’s wife, is a complete nonentity. No one has a bad word to say about her; she is, as Nevinson calls her, un coeur simple, who lives “strictly in the present” without a “moment for reflection, rumination, contemplation, to look to the future, still less look back at the past.” Piling synonyms and near-synonyms on top of one another is a hallmark of Marías’s prose style: To my mind, it usually works, giving Nevinson’s narration a personal voice and rhythm, though occasionally it feels just a little bloated. (Not much is gained by writing, “It’s done, it’s over, it’s finished.”)

The plot may be pulpy on the level of what one might expect of thrillers sold at airports, but it is self-consciously pulpy. And it really is, as publishers like to say, “captivating.” But to call it a “page-turner” would be to cheapen it, for that phrase implies that there’s nothing in the prose that makes the reader pause to reflect. Much of the novel consists of Nevinson’s musings about secrecy, betrayal, and justice. Digressions follow digressions, in a good way. Nevinson works up to saying that he’s been tasked with killing a woman by contrasting the executions of Anne Boleyn and Marie Antoinette; he reflects on the justice of extrajudicial assassination by way of Fritz Lang’s Man Hunt (1941) and the tragic life of Friedrich Reck-Malleczewen, the anti-Nazi German who, having missed the perfect opportunity to kill Hitler in 1932, died in Dachau in 1945.

Nevinson remarks that he “never really accustomed myself to the idea that so many … men and women of action if you like, so many agents, were also highly cultivated.” That’s Marías’s rather transparent way of accounting for Nevinson’s keen mind. Nevinson lectures the reader on subjects such as Chateaubriand’s Memoires d’outre-tombe and the Esquilache riots of 1766. The willful forgetting of history is a leitmotif. Thus, when Tupra’s brash subaltern Nuix hasn’t heard of the 1527 sack of Rome, Nevinson reflects that Nuix reads books only about the 20th century “as if nothing that happened before could be of any use to her or even concern her.” Nevinson, in turn, is chided by Tupra for not having read the full Rebecca West oeuvre. Not for nothing were Tupra and Nevinson recruited to the secret services by an Oxford don.

Marías is a stylist of rare stature; kindly critics have often compared him to Proust, if Proust had written thrillers. But Proust’s looping sentences were far more intricate — the longest, I believe, is a little more than 1,000 words — and he placed more emphasis than Marías on sensory impressions. Proust’s literary references were, moreover, primarily French, while Marías is schooled in the English canon, having translated Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy to great praise in his early twenties. Lines from Macbeth and T.S. Eliot’s “Little Gidding” recur throughout Tomás Nevinson, as do quotes from William Blake, John Donne, and Wilfred Owen.

The right comparison is far more obvious than Proust: W.G. Sebald. Sebald even called Marías his “twin writer.” They were both Europeans with English sensibilities, spending parts of their lives in provincial England (Marías in Oxford, Sebald in East Anglia). They inserted photographs in their books in a very similar fashion. As if to emphasize their mutual affinity, Marías even has a character in Tomás Nevinson read Sebald’s The Rings of Saturn. And both were preoccupied by the cataclysms of the 20th century.

Still, Marías is a fine stylist: If the plot carries one through a first reading, it’s Marías’s digressive musings and comedic talent that make it worth revisiting.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Gustav Jonsson is a Swedish freelance writer based in London.