Comic gold

Michael Taube

What is a graphic novel? Merriam-Webster defines it as “a story that is presented in comic-strip format and published as a book.” Some early historical examples of what we now know as graphic novels certainly followed this model. Swiss cartoonist Rodolphe Topffer’s 1837 comics masterpiece, Histoire de M. Vieux Bois, for instance, became America’s first graphic novel when it was reprinted as The Adventures of Mr. Obadiah Oldbuck in 1841. German painter/illustrator Wilhelm Busch’s Max und Moritz, published in 1865, is a brilliant children’s story with comic illustrations and a graphic novellike feel. Canadian cartoonist/illustrator Palmer Cox’s The Brownies series between 1887-1918 and The Yellow Kid in McFadden’s Flats, an 1897 collection of Richard F. Outcault’s legendary comic strip, both drew an intriguing parallel between comic strips and stories. Modern graphic novels, such as Jim Steranko’s Chandler: Red Tide, Don McGregor and Paul Gulacy’s Sabre, and Jules Feiffer’s Tantrum, along with Marvel Comics’s graphic novel series and D.C. Comics’s The Dark Knight Returns and Watchmen, also employed this traditional style.

As someone who’s read, and reviewed, books on animation and classic comic strips for decades, I have a different interpretation of graphic novels. They’re much more than Merriam-Webster’s narrow and open-ended definition makes them out to be.

Take the work of Francisco Martinez “Paco” Roca, long regarded as one of Spain’s finest cartoonists. He’s blended real historical events and personal stories into his graphic novels with an artistic genius and flair that few have been able to match. In many ways, he’s the perfect graphic novelist for those who don’t really get graphic novels.

Roca grew up reading superhero comics and cartoonists like Frank Miller, who created the Dark Knight series. He was also heavily influenced by European-style comics and graphic novels, including the Franco-Belgian bande dessinée tradition. There are aspects of Herge’s The Adventures of Tintin, Rene Goscinny and Albert Uderzo’s The Adventures of Asterix, and Jean-Michel Charlier and Jean Giraud’s Blueberry that glisten in Roca’s books, from the visual component to powerful storylines. The nonfiction element that has appeared in some modern North American graphic novels, including Will Eisner’s A Contract with God and Other Tenement Stories and Art Spiegelman’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Maus, may have also caught the cartoonist’s eye in his formative years.

The Spaniard’s first great success was in 2007 with Wrinkles (“Arrugas”). It’s a graphic novel about a group of senior citizens who decide to rob a casino during a visit organized by their residence. Why? They discovered a person can’t be jailed for committing this type of crime after turning 70 years old. The gradual aging of our parents, combined with the father of fellow Spanish cartoonist Diego Ruiz de la Torre Gomez de Barreda, or “MacDiego,” suffering from Alzheimer’s disease, motivated Roca to write this tale. His book was highly acclaimed in Spain, and it was translated into English in 2008 by Britain’s Knockabout Comics. It was later adapted into an animated film in 2011 that was short-listed for an Oscar.

The success of Wrinkles has led to additional English translations of Roca’s brilliant work. Fantagraphics, a well-known U.S. comics publisher, has released a few of them through its European graphic novel line.

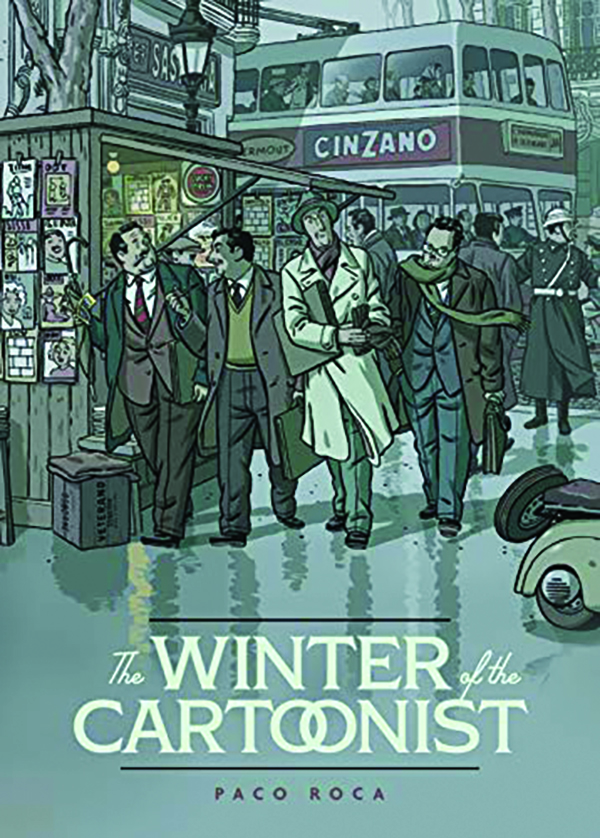

The Winter of the Cartoonist (“El Invierno del Dibujante”) was translated into English in 2020, which is nine years after the original Spanish edition was released. It’s the fascinating true account of five Spanish cartoonists, Carlos Conti, Guillermo Cifre, Eugenio Giner, Jose Penarroya, and Jose Escobar Saliente, who abruptly left the powerful Editorial Bruguera publishing house in 1957. They were frustrated with the poor working conditions and low pay, archaic contracts where they would lose complete control of their characters, and a fundamental lack of creative freedom and artistic integrity. So they struck out on their own, formed a cooperative, and launched an independent humor magazine, Tio Vivo.

The cartoonists’ revolt was short-lived. The cost of running a magazine in fascist Spain was exorbitant. Editorial Bruguera also had influence with national distributors, which limited Tio Vivo’s availability on newsstands and profits. The magazine was acquired by their former employer in 1959, and they returned to their old haunting grounds, with the exception of Giner. Although Goliath had slain David, the cartoonists had courageously chased a dream and proved the status quo in the Spanish publishing industry could be and must be challenged. They earned the respect of their colleagues, and they went on to help build a new comics revolution in their country.

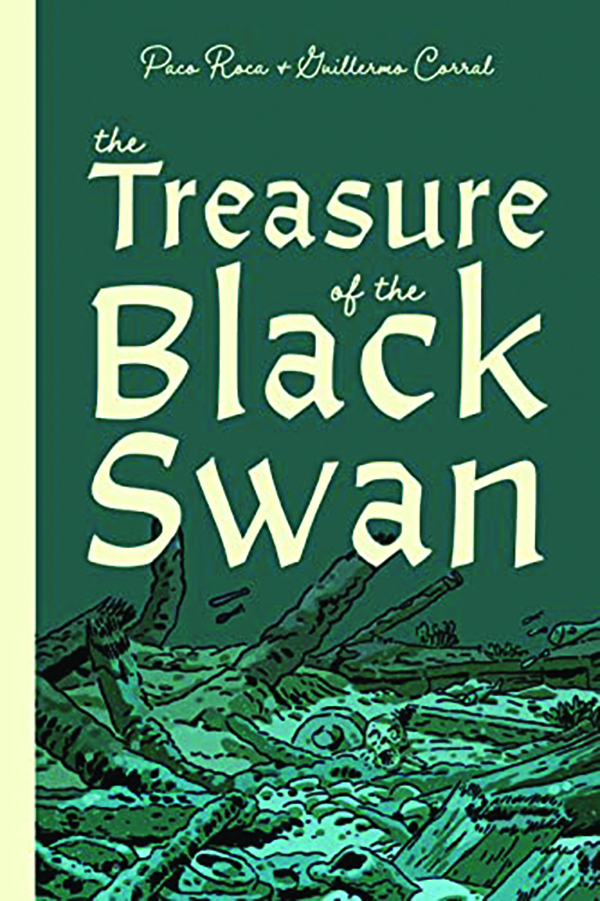

Fantagraphics’s most recent English translation of Roca’s work is The Treasure of the Black Swan (“El Tesoro del Cisne Negro”). Originally published in 2018, it was adapted by Spain’s Movistar+ and AMC Studios for the acclaimed 2021 TV miniseries La Fortuna, starring Stanley Tucci. For those who are fascinated by Spanish and European naval history, as well as the search for treasure buried many leagues under the sea, this is an incredible story of imagination and intrigue.

The Nuestra Señora de las Mercedes, a Spanish vessel, was sunk by the British Royal Navy off Portugal’s southern coast on Oct. 5, 1804, during the Battle of Cape Santa Maria. It carried an expensive secret to its watery grave: Roughly $500 million in silver and gold coins lay undisturbed for over two centuries. When the dark veil covering the Black Swan Project to recover the ship was first lifted in May 2007, many people were immediately intrigued to learn about mountains of historical bullion resting on the ocean floor.

The U.S.-based Odyssey Marine Exploration announced the recovery of 17 tons of coins from the wreckage. Alas, it was heavily criticized for the way it had secured the treasure amid questions over territorial water claims. Political disputes erupted between several countries, including the United States, the United Kingdom, Spain, and Panama. It led to many hard feelings and a lengthy court battle.

Co-writer Guillermo Corral, a former diplomat, was involved in the legal tussle with Odyssey. He teamed up with Roca to turn this real-life story into an illustrated account, albeit with some dashes of artistic liberty.

In Roca and Corral’s version, low-level Spanish diplomat Alex Ventura finds himself entangled in the mysterious identity of a sunken ship. Ventura and his romantic interest, Elsa, come into contact with self-described “amateur historian” Horacio Valverde de la Torre. He believes the Mercy, a ship tied to the Spanish navy and generalissimo Manuel Godoy, who later served as Spain’s first secretary of state from 1792-97 and again from 1801-08, is the elusive Black Swan. An intrepid cast of characters, including politicians, lawyers, and several shadowy figures, are involved in this gripping legal/political drama and race against time.

Corral and Roca’s engaging storyline and penetrating historical research, combined with the latter’s artistic brilliance, have created a mesmerizing graphic novel with the look and feel of a classic Tintin story. It’s truly a comics masterpiece.

The next time you walk by the comics section while perusing a bookstore, you may want to look and see what it’s offering. Politics and history buffs may be surprised to discover that the work of Paco Roca and other cartoonists could very well be up their alley.

Michael Taube, a columnist for four publications (Troy Media, Loonie Politics, National Post, and Epoch Times), was a speechwriter for former Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper.