The meaning of performative violence

Ben Sixsmith

One day in March 2008, Stephen “Steve-O” Glover, effectively maddened by a chronic drug addiction, emailed his Jackass colleagues to tell them that he planned to drive his motorcycle out of the window of his apartment. He wanted them to come and film the suicidal stunt. Johnny Knoxville and his other Jackass pals rocked up all right — but instead of creating the movie of his death, they picked him up and drove him off to rehab. He’s been sober almost ever since.

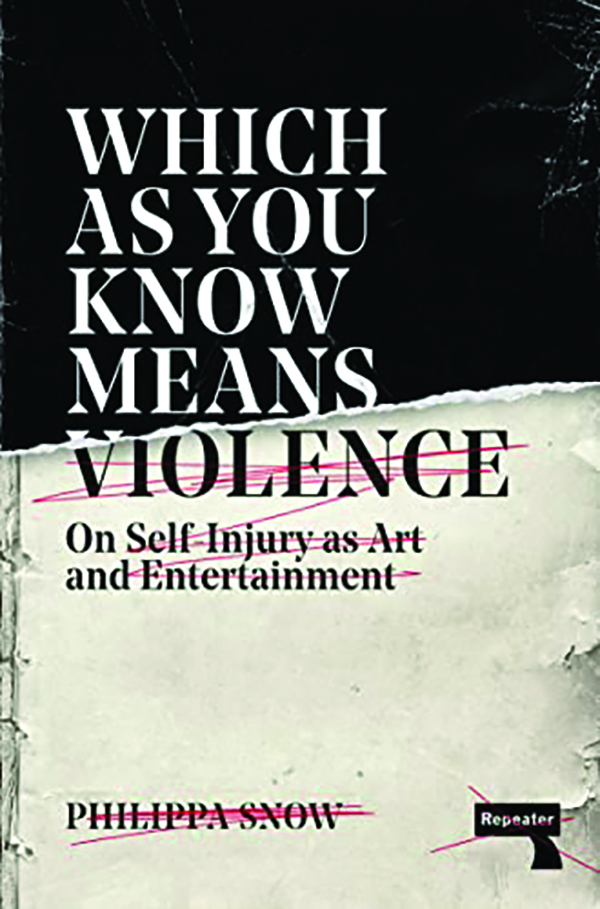

Accidentally, Steve-O had identified an important distinction. The fun of Jackass was in its cheerful, reckless performers narrowly escaping death and incapacitation. Their inevitability was no fun at all. In Which as You Know Means Violence, an exploration of “self-injury as art and entertainment,” Philippa Snow writes that the “self-injurious performance artist” is preoccupied with death, “but quite often they are courting it in order to feel or demonstrate that they are in fact still alive.” To come close to death, but to avoid it nonetheless, has an affirmative quality.

Which as You Know Means Violence attempts to take Jackass as seriously as Marina Abramovic in its contemplation of violence as art and “pain as an effective vehicle for profundity, liberation, feminism, subversion, eroticism, humour and divinity.” It is an interesting, engaging, but ultimately frustrating work of cultural criticism.

Snow ran the risk of taking silliness too seriously. Actually, I’m not sure she is serious enough. The book is beautifully written and contains some keen insights, but it is opportunistically ideological. Snow writes, for example, that Jackass “takes aim at America,” but this obscures how it is both a satire and celebration of the USA — an absurd manifestation of the American dream. What united the cast as much as genital humor was a bone-deep desire to “make it” — even if that meant being trampled by a bull and kicked in the nuts.

Nor is it, as Snow suggests, philosophically evocative of post-9/11 life. It is far more a child of the ’90s — a raging remnant of the “thumos” that Francis Fukuyama saw as being drained from comfortable post-history existence. When Snow suggests that ringmaster Johnny Knoxville’s career might have been shaped by “the contextualising bleakness of America in the immediate aftermath of 9/11,” she is being bizarrely ahistorical. As Snow writes elsewhere, Jackass began in 2000, and Knoxville had been doing similar dark and dangerous stunts for Big Brother magazine for years.

It might seem peculiar to take an analysis of an obscene stunt show quite this seriously, but the point I am prowling toward is that intellectual analysis of pop culture that purports to expose its hidden aesthetic or social relevance often misses the point on the most basic level. Writers would never get away with saying The Waste Land was inspired by World War II, but the lofty heights from which they judge more unsophisticated entertainment allows mistakes to sit unnoticed.

The charge of “politicization” is often philistinic. All culture can have political or at least social implications. When culture is assessed through a specific political lens, though, it can diminish rather than expand its significance. Why a man committing or enduring violence is perceived differently from a woman committing or enduring violence is a valid question. Snow considers it for page after page, though, while other interesting, telling aspects of “self-injury as art and entertainment” go underexplored.

For example, Snow discusses how the BDSM-influenced performance artist Ron Athey used self-harm as an escape from religious guilt. It reminded me of the professional wrestler Matt “Nick Mondo” Burns’s documentary, The Trade, which explores how his dangerous and agony-inducing style was influenced by shame-soaked evangelical rhetoric about the suffering of Christ. I would have been interested in more on this theme. But soon Snow was talking about how performers on the joyless Rad Girls, a female take on Jackass, could not accept being punched in the face “not only because breaking one’s nose is extraordinarily painful but because to do so as a woman is to risk permanent damage to one’s value as a commodity if it can’t be fixed.” It is perhaps worth pointing out that the Jackass cast members risked permanent damage to their value as a commodity, inasmuch as they could be killed or maimed, in almost every skit.

Still, there are interesting thoughts here. “It may be that Christ [is] the greatest artist of all time,” Snow writes:

… since whose death has since been more analysed by fans, denounced by critics, and paid homage to by other artists? Good art, as a great number of artists have insisted throughout history, is first and foremost about sacrifice, a willingness to disappear into the medium and the message fully enough that life itself becomes a secondary concern.

Snow could have gone further in exploring how consumers of popular culture can demand suffering from its creators. Inflicting and experiencing pain becomes a mark of morbid authenticity in a world in which so much is manufactured and spun. There is the death-match wrestler who is cut with glass and struck by chairs to prove that while the competition is staged, the suffering is real — or the drill rapper who endangers others and themselves to prove that they are really “on job.” Abramovic’s dark 1974 work of performance art, Rhythm 0, in which an audience was invited to give her pain or pleasure with the use of various objects, and which Snow writes about well, is eerily evocative here — even if these artists are more than capable of inflicting violence themselves.

“I am fascinated by the idea that our civilization is like a thin layer of ice upon a deep ocean of chaos and darkness,” Werner Herzog (himself no stranger to introducing real pain into the filmmaking process) told the author Paul Cronin. Suffering in art and entertainment allows us to peer through at the results of our more primal instincts. Still, we should remember that just to feel alive, or just to make the audience feel alive, we are standing on the ice separating the air from the cold waters of death.

Ben Sixsmith is contributing editor at The Critic.