In defense of old cranks

Peter Tonguette

Youth, or its appearance, rules the modern world. Women in their 60s dress in the style of teeny-boppers. And men in their 50s fill their time with video games. Meanwhile, plastic surgery, Botox, and assorted pharmaceutical interventions promise that the aged can look as youthful (or, at least, as stretched) as their juvenile overlords. Social media, a medium that feasts on the sort of cattiness once associated exclusively with junior high, is the dominant form of communication.

The cult of youth has been with us since the Romantic Era, but Madison Avenue, Silicon Valley, and Hollywood have assured that it has become a full-blown religion. Nowadays, most movies and TV shows seem to be engineered to appeal to audiences somewhere between the ages of 13 and 31. Comic books are spoken of seriously and superheroes solemnly. Grown people congregate online to scrutinize the latest Star Wars spinoff, Spider-Man reboot, or Indiana Jones sequel.

The large exception to the rule is Washington, the sole remaining power center in America in which the old are still in control — much to the worry of everybody else in our youth-obsessed land. One of the first signs of the devaluation of seniority and experience in the nation’s capital came during the now-quaint 2008 presidential campaign of John McCain, whose age and mental wellness were consistent fodder for his opponents. These days, President Joe Biden has become a national joke less for the failure of his policies or the incompetence of his administration than for falling down and snoozing like the octogenarian he is. Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-CA), a year removed from her 90th year, has faced endless entreaties for her to resign amid tabloidlike gossiping about her intellectual capacity and equally salacious speculation about her physical well-being. Sensing blood in the water, Republican presidential contender Nikki Haley proposed “mental competency tests” for political aspirants north of 75.

To which I say: Be careful what you wish for. Each of us one day will be among the ranks of the infirm. Furthermore, the rampant youth worship throughout America today, and the attendant ageism that informs the noxious attitudes toward Biden and Feinstein’s senescence, is countered by millennia of great art made by old cranks.

Let’s ask Orson Welles, several of whose best films, including The Magnificent Ambersons, Chimes at Midnight, and The Other Side of the Wind, portrayed the war of the young on the old. “You told me last night about all these old directors whom people in Hollywood say are ‘over the hill,’ and it made me so sick I couldn’t sleep,” Welles once said to his friend Peter Bogdanovich. “I started thinking about all those conductors — Klemperer, Beecham, Toscanini; I could name almost a hundred in the last century — who were at the height of their powers after 75 and were conducting at 80.”

The argument for artists working until they keel over is admittedly more straightforward than for public servants hanging on until they reach senility. Unlike politicians, artists are not responsible for the laws under which we live or the wars by which we might die. They merely must make good art, and the great ones, such as the conductors revered by Welles or Welles himself, almost invariably do so until the very end. Any of us can point to major artists whose gifts flowered for a final time late in life: Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard, Edward Hopper’s painting Intermission, Frank Sinatra’s Trilogy album, Saul Bellow’s Ravelstein. Cussedness, infirmity, or declining “mental competency” were not impediments to the creation of any of these works.

In fact, late works are often defined by a “don’t-give-a-damn” openness. By all accounts, Philip Roth ended his life as a cantankerous grump, and his final novels, including the masterly Indignation and The Humbling, are fittingly despairing. Failing to produce a workable novel out of his last major literary project, Kurt Vonnegut offered up a shapeless though lovely hodgepodge of fiction and autobiography, Timequake. It is as though the strain of the act of creating compels aging artists to say what they must and nothing more. Consider the terse, taut last works of Ernest Hemingway (The Old Man and the Sea), John Cheever (Oh What a Paradise It Seems), and Joseph Heller (Portrait of an Artist, as an Old Man). In their last books, Joan Didion and Susan Sontag produced exacting sentences that seemed arrived at only with strenuous effort.

Moviemakers approaching the autumn of their lives also enjoy a last burst of expressiveness. Kurosawa’s Madadayo, Bunuel’s That Obscure Object of Desire, and Altman’s A Prairie Home Companion are often as weird, as open, as broken-down as any of the old members of our decaying ruling class. And they are the more fascinating for it.

Alfred Hitchcock discarded his English gentility with a next-to-last film of rare violence and brutality, Frenzy. Howard Hawks made himself (but few others) happy with a trio of Westerns that shamelessly used and reused the same setup and star: John Wayne in Rio Bravo, El Dorado, Rio Lobo. George Cukor, who was gay, made a startling reference to his sexuality in his last film, the masterpiece Rich and Famous. In the closing scene, longtime female friends played by Jacqueline Bisset and Candice Bergen kiss each other on New Year’s Eve. “I want the press of human flesh, and you’re the only flesh around,” Bisset says — her words serving as a beautifully unguarded, yet elegantly oblique, admission of Cukor’s true self.

If we want art to teach us something about life, beauty, civilization, or the cosmos, it follows that the old have more to tell us than the young. I have always gravitated toward works by older artists for this reason. The most significant artistic event in my lifetime was the release of the final film of Stanley Kubrick, Eyes Wide Shut. Why did I spend half of my teenage years so eagerly anticipating its release? Because I regarded Kubrick, in his late 60s when he made the movie, in the same way that I regarded nearly all old people: as an oracle, a seer, a wise man. Nearly five decades of filmmaking gave Kubrick infinitely more directorial tools at his disposal than his younger colleagues. Nearly seven decades of living gave him a far more nuanced picture of the world. We know deep down that old age, even when marred by ill health, confers authority and that youth, even when boosted by outward vigor, suggests superficiality.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

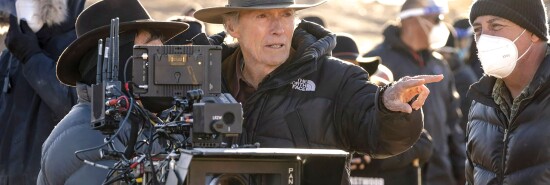

Later this year, 93-year-old Clint Eastwood will embark on what is supposed to be his final directorial outing, but let us hope it is not. “When old age tempts or forces a man to give away the very source of his ascendancy over the young — his power — it’s they, the young, who are the tyrants, and he, who was all-powerful, becomes a pensioner,” Welles once said in a proposal for his never-made film of King Lear. Young tyrants today see their inevitable rule as benign, and so the sooner, the better. But if Eastwood does not belong behind a movie camera, where, exactly, does he belong?

So who has something to learn from whom? Should the arts teach the consumer culture and the political culture a thing or two about the old or the other way around? Today, to show signs of advancing age — to speak softly, to walk slowly, to be forgetful, weary, or grouchy — is now to invite open ridicule as never before. “Respect for one’s elders shows character,” says Harvey Keitel’s Winston Wolf in Pulp Fiction, and we have precious little of it.

Peter Tonguette is a contributing writer to the Washington Examiner magazine.