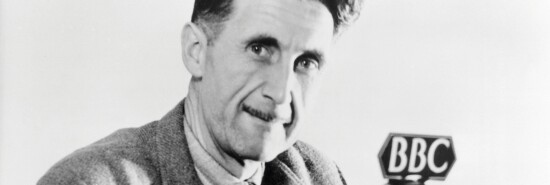

Thinking doubly hard about George Orwell

Michael Moynihan

A year into the Iraq War, the Chicago Tribune asked if it was “any surprise, as we barrel further into political conflict in Iraq and assess our role as a global power, that local theater companies are staging adaptations of George Orwell’s books.” At about the same time, I was compelled by a radical friend to watch a documentary with the clumsy title Orwell Rolls in His Grave, which argued that America’s supplicant media were indistinguishable from the Ministry of Truth, that sinister propaganda factory from his anti-Stalinist classic 1984. After the election of Donald Trump, frightened Americans, presumably in anticipation of their country’s long slide into dictatorship, ensured that 1984 sat atop the Amazon bestseller list for weeks.

George Orwell would likely wince at how easily he tempts polemicists and paranoiacs toward a sort of narcissistic presentism: ours as a uniquely undemocratic epoch, the prophecy of 1984 fulfilled, the endpoint on the long march toward Big Brother. The habit of viewing contemporary crises through the presentiments of the past inevitably leads to an Orwell quote, usually wrenched from context, and a lazy invocation of 1984, which despite its modest length and manageable prose, seems more cited than read.

DAVE BARRY LOVES FLORIDA ENOUGH TO SKEWER IT RIGHT

It’s inarguable that 1984 ranks as the most politically influential novel of the 20th century, if only for contributing “doublethink,” “memory hole,” “newspeak,” “thoughtcrime,” “unperson,” and “Big Brother” to the political lexicon. Animal Farm, Orwell’s other anti-communist allegory, isn’t far behind. For those who have read 1984, and understand the basics of its etymology, most contemporary comparisons — with the usual exception of North Korea — tend to feel overdrawn. And the hackneyed term “Orwellian” has been so misused that it now aligns with Orwell’s own complaint about the calculated imprecision of political speech. Take the word “fascism,” Orwell wrote in 1946, which “now has no meaning except in so far as it signifies ‘something not desirable.’”

Orwell is that rare intellectual whose mantle everyone wants to claim, someone whose beliefs were internally consistent and unambiguous yet whose legacy has been kidnapped by those on the Left and Right. These conjurers of Orwell’s ghost are guilty of what his biographer John Rodden called “intellectual grave robbing.” But the real George Orwell was a more complicated figure. He so loathed the idea of someone writing about his life, something that seemed far from necessary during his lifetime, that a no-biography clause was enshrined in his will. But his wealth and renown would come in the afterlife, and there would be no stopping the flood of books examining everything from Orwell’s health to his love for gardening.

The critic and scholar D.J. Taylor has now taken a second crack at an Orwell biography. It appears an odd choice, considering there was little to improve upon in his brilliant 2003 book Orwell: A Life. But as new material has trickled out of various archives, Taylor undertook a reassessment, producing the exhaustive, definitive, not-soon-to-be-surpassed Orwell: The New Life. In the crowded field of Orwell studies, Taylor’s trenchantly observed portrait will be the standard to exceed, written in beautifully rendered prose that adheres to his subject’s admonition that good writing should be “like a window pane.”

The precis of Orwell’s life is familiar. The son of a colonial official in British India who sold opium to the Chinese, Orwell was born into what he called the “lower-upper-middle-class” — stolidly British, hardly wealthy, an Etonian but on scholarship. As seems customary for English writers of his generation, he was brutalized at school, where he developed a keen hatred of authority. Taylor points out that while Orwell’s account of the “awful nightmare” of his early schooldays, the lurid essay “Such, Such Were The Joys,” is broadly true, its barbarous details were contested by friends and contemporaries.

After leaving school, Orwell carried on the family tradition of colonial service by working as a policeman in Burma, where he would develop a keen hatred of imperialism; the British empire was a birthright he was eager to disinherit. While Orwell considered colonialism a moral stain on his homeland, he was nevertheless surprisingly patriotic and, Taylor writes, “hopelessly in love with the past.” His childhood friend Cyril Connolly quipped that he was a “rebel in love with 1910.”

When investigating the squalid conditions of the British working class, Orwell’s upbringing wasn’t easily camouflaged. Betrayed by his upper-class accent, he appeared “an imposter vainly trying to disguise himself in an environment where no disguise is possible.” Despite his vocal solidarity with the proletariat, “he was a man of his class and couldn’t break from it,” a radical forever loyal “to the caste that created him.”

Orwell’s enchantment with socialist politics, which felt instinctual rather than ideological, informed his early novels and reportage but would be tested when, in 1936, he volunteered to fight in the Spanish Civil War, a cause that obsessed the British intellectual class. It was Spain, Taylor says, that “made him a different person.”

Upon arriving in Barcelona, he wrote to Connolly that in his brief time in the country, he had “seen wonderful things, and at last [I] really believe in Socialism, which I never did before.”

But it was here that Orwell witnessed the totalitarianism encoded in the DNA of the Stalinist Left, where various antifascist factions were too busy fighting each other to wage war on the fascist enemy effectively. This should have come as no surprise to Orwell, considering that in the waning days of the Weimar Republic, the intramural battles on the Left had done much to facilitate Hitler’s occupation of the chancellery. Fascism had to be defeated, said the communists, but so did the “social fascism” of our enemies on the Left.

When Orwell submitted an article critical of Soviet interference in Spain to the New Statesman, it was rejected on grounds that would become familiar. While the magazine’s editor acknowledged the essential truth of his argument, he worried that it would “damage” the communist cause. When Orwell produced his book-length account of the war, Homage to Catalonia, it was rejected by his publisher on the same grounds.

Indeed, two of his most politically significant works, Homage to Catalonia and Animal Farm, were met with varying degrees of skepticism and hostility by publishers, often out of sympathy for one of history’s greatest tyrants. And as a result, Taylor writes, Orwell “believed that he was the victim of a truth-extinguishing left-wing plot.”

Orwell had come to understand that the “prevailing orthodoxy [in England] is an uncritical admiration of Soviet Russia” and that anything deviating from this was “next door to unprintable.” In an unpublished preface to Animal Farm, he warned that “the English intelligentsia, or a great part of it, had developed nationalistic loyalty toward the U.S.S.R.” There is a bit of overstatement here, but not much. In both America and the United Kingdom, we tend to remember Stalin’s Western influence as existing only in the fevered imagination of McCarthyites and Birchers. But the briefly opened Soviet archives did much to complicate this narrative — and confirm Orwell’s suspicions.

It is doubtless true that he would have had an easy time finding publishers for books on the evils of fascism, a theme always lurking, but rarely explicit, in Orwell’s writing. But he understood “that there would be great difficulty in getting [Animal Farm] published.” And indeed, there was. Orwell’s publisher Jonathan Cape was visited by an official of the Ministry of Information, who advised against publishing Animal Farm lest it offend Britain’s allies-of-convenience in Moscow. Shamefully, Cape complied. And it wasn’t until 1991, with the collapse of the Soviet Union, that the ministry official, Peter Smollett, would be publicly unmasked as a Soviet agent.

By the time 1984 was published in 1949, six months before Orwell’s untimely death, the political climate had shifted, high-born Western Stalinists were out of favor, and the book was a critical and commercial success. After all, one couldn’t convincingly lie about purges, gulags, and institutionalized state repression forever. Plenty of writers have weighed in on whether the “prophecies” in 1984 have been “realized.” But the book is more revelation than prophecy; only a slight fictionalization of Stalin’s contemporaneous terror state. Immediately after the book’s publication, Orwell wrote that these themes had “partly been realized” by both communism and fascism.

But he was, Taylor argues, “eerily prophetic” on the post-war political landscape, particularly the coming “cold war,” an Orwell coinage. But he is also right to point out that this wasn’t always the case. His celebrated 1941 essay “The Lion and the Unicorn” is crammed full of predictions that “now seem hopelessly awry,” says Taylor. Indeed, one can’t help but wince when reading sentences such as this: “The lady in the Rolls-Royce car is more damaging to [British] morale than a fleet of Goering’s bombing planes.”

Orwell biographer Christopher Hitchens often said, quite rightly, that Orwell was correct about the three great subjects of the 20th century: imperialism, fascism, and Stalinism. But on this, he was hardly alone. More impressive was his prescient writing on the subversion of language, foreseeing the rise of obfuscatory academic jargon (is there anything he would have hated more than postmodernism?) and warning that simple euphemism was often employed to conceal the sinister. The barbarian state of East Germany, which had no republican or democratic tendencies, was officially known as the German Democratic Republic. The national newspaper of the Soviet Union, within which not a syllable could be trusted, was tauntingly called Pravda, the Russian word for truth. And so on.

Reading Taylor’s book, one cannot help but have contempt for those “intellectual graverobbers” who deny the complications of Orwell’s thought in service of cheap ideological point-scoring. He is celebrated by conservatives, though he protested the idea that he was one of them, clarifying in 1945 that “I belong to the left and must work inside it, much as I hate Russian totalitarianism and its poisonous influence in this country.” He stressed that 1984 wasn’t an attack on socialism but did worry that socialism “is not inherently democratic.” And in common with many on the Right, Orwell saw moral equivalence between the 20th century’s two monstrous ideologies, writing in a 1947 letter to journalist Richard Usborne that there was “not much to choose between communism and fascism.”

Orwell’s legacy is one forever connected to the failures and violence of communism, his name forever associated with the obscenities of totalitarianism. The very availability of his catalog is one of the best measures of a country’s political freedom. For the dissident writer, the enemy of cant and doublethink, there can be no greater legacy.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Michael Moynihan is a host of The Fifth Column podcast.