It was once believed that new technologies — powerful cameras in phones, sophisticated yet intuitive digital editing tools, the internet itself — would transform Hollywood by liberating and empowering filmmakers, allowing them to shoot wherever and whenever they wanted, producing professional-quality material without depending on meddling studios to front the capital.

“I’m very aware as a creative person that those who control the means of production control the creative vision,” George Lucas told Forbes in 1996, as he schemed to unleash Jar Jar Binks on an unsuspecting world. The context was a profile not just of Lucas himself, but of Skywalker Ranch, his digital Shangri-la in Marin County, where untold millions of dollars’ worth of technology are marshalled today toward filling an ever-expanding universe of Star Wars content with its computer-generated elements.

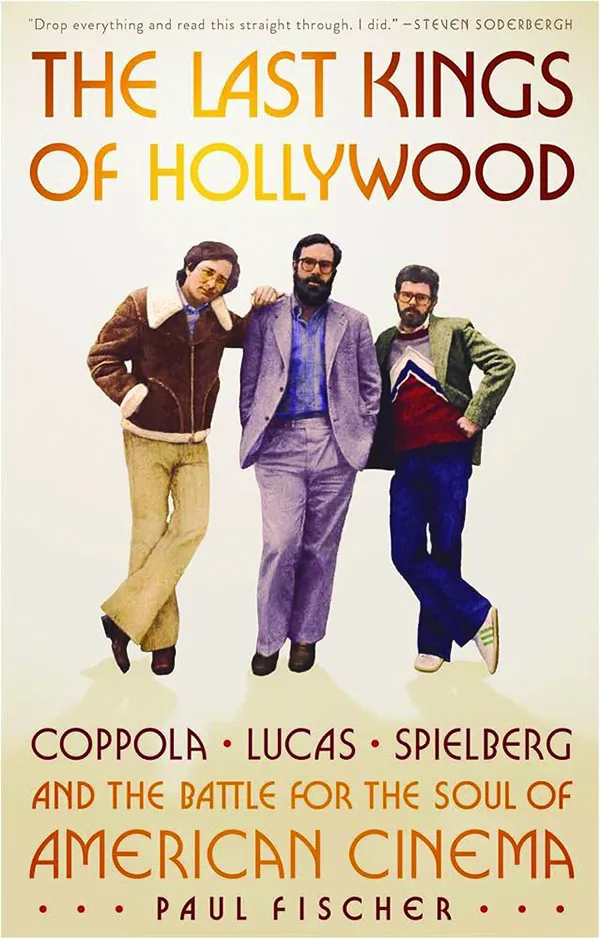

The Last Kings of Hollywood: Coppola, Lucas, Spielberg—and the Battle for the Soul of American Cinema is an attempt by the culture writer Paul Fischer to explain how the iconoclastic, shot-calling cinematic auteurs of the 1970s inadvertently pulled up the ladder behind them and ceded the cultural field to bland franchise fare. Lucas’s self-awareness — Fischer quotes him from the same profile as saying “All studios are going to look like what we are,” that is, part software company — was limited characteristically to the technological. While anyone can, in theory, make a movie, what a studio will pay for remains tethered to boardroom logic, a phenomenon for which Lucas and his cohort are largely responsible.

Fischer begins his story with Lucas’s lifelong frenemy/rival, Francis Ford Coppola. A young, promising director from the University of Southern California’s film school, Coppola was dissatisfied with the studio fare handed to him, such as Finian’s Rainbow, a preposterous, out-of-touch musical about a leprechaun, and a vehicle for a near-septuagenarian Fred Astaire. Coppola’s desire to make movies on his own terms would consume him for the rest of his life, but it began with his striking out on his own and starting an artist-driven subsidiary of Warner Bros. called American Zoetrope.

Zoetrope’s first film, completed without an iota of pesky studio meddling, was Lucas’s THX 1138 (1981), a feature-length version of his revered USC student film. A turgid, unoriginal riff on Orwellian dystopia, the studio hated it, and audiences did as well when it was finally released in theaters after an agonizing back-and-forth with Warner Bros. over ultimately minor edits. That was the end of Zoetrope, at least in its idealized form. But the idea of filmmaking without compromises would dog Coppola and Lucas for the rest of their days, although to decidedly different ends.

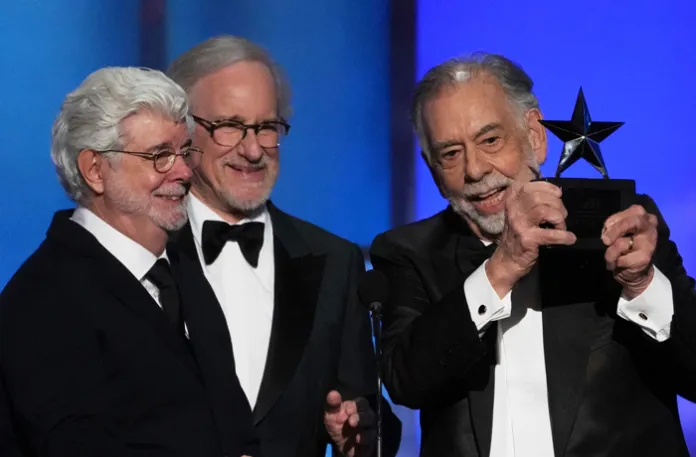

It’s amusing and instructive to consider the interpersonal contrast between the men, as Fischer highlights with aplomb: Coppola the ebullient, bellowing, Italian-American paterfamilias and hopeless romantic bleeding for his art; Lucas, the awkward, laconic, gadget-obsessed tinkerer from Modesto, California, more comfortable in the cool silence of the editing suite than, well, anywhere near another human being. Despite squabbles both personal and professional, the two remain lifelong friends, with Coppola toasting Lucas before he received his honorary Palme d’Or at Cannes in 2025.

Perhaps more naturally attuned to the nerdy Lucas was Steven Spielberg, the partnership between them serving as the catalyst for Fischer’s thesis about the creative decline of Hollywood. Spielberg had his own neuroses rooted in his peripatetic background, his parents’ tumultuous marriage, and his outsider status as a Jew growing up in conformist McCarthy-era suburbia, later to be told in his 2022 cinematic roman a clef The Fabelmans. While Spielberg’s filmmaking had, in spades, the warmth and human touch that Lucas’s lacked, they shared a juvenile obsession with the comic book and film serial culture of their youth that led ultimately to the creation of the Indiana Jones franchise.

Fischer pins the transformation of the film industry on the contemporaneous rise of figures such as Barry Diller and his “Diller’s Killers” at Paramount Pictures, which jumped at the chance to release “high concept,” easily franchised fare of the exact sort that Lucas and Spielberg were perfecting. If the business side of the movie industry could be characterized in the 1970s by figures like the louche, risk-taking Robert Evans, figures like the sharklike, no-nonsense Diller — or, better yet, the maniacal, coke-frenzied Don Simpson, who partnered with Jerry Bruckheimer on hits such as Flashdance (1983) and Top Gun (1986) and lifted weights with Arnold Schwarzenegger — owned the 1980s.

Lucas and Spielberg’s stars rose as Coppola’s waned, with a series of ruinous financial experiments forcing Coppola to produce quieter, more workmanlike fare through the 1980s as he paid off immense debts. While Fischer’s book is more history than cultural criticism, the kernel of an analysis is there: Coppola and Lucas shared the same desire to make the art they wanted, on their own terms; it just so happened that what Lucas wanted aligned precisely with Hollywood’s transformation into a single-minded global enterprise for middlebrow fantasy entertainment.

The Last Kings of Hollywood is a pleasure to read and captures its tritagonists’ characters remarkably well for a 400-page book with such a broad scope. At the same time, Fischer seems overly content to linger on anecdotes that are by now biblically familiar to cinephiles (to wit: Coppola’s righteous struggle to cast Al Pacino in 1972’s The Godfather, Lucas’s anti-charisma and the misery it wrought on the set of Star Wars, the malfunctioning boondoggle that was the titular animatronic in 1975’s Jaws). He also spends an arguably disproportionate amount of time on the three directors’ marriages and romantic entanglements, which, while compelling as biography, shed little light on the dynamic between the three at the center of the book.

MAGAZINE: CHUCK KLOSTERMAN PROBES THE MEANING OF FOOTBALL

Still, it’s difficult to deny Fischer’s insight that the struggle for technological independence from Hollywood might not inherently lead to anything more artistically noble than the schlock Coppola and Lucas meant to supplant. The surprise box office hit of the year thus far is Iron Lung, a self-financed video game adaptation written, directed, edited by, and starring Mark Fischbach, better known as the YouTube megastar Markiplier. It’s hard to imagine a film more directly in the lineage of Lucas’s dreamed-of technological emancipation from the studio system. And yet, even an otherwise mutedly positive review from IndieWire felt obligated to describe it as “at times astonishingly boring.” More caustically, the Guardian called it “not unlike spending 12 hours on Twitch with all the curtains closed.”

Moments like those described in The Last Kings of Hollywood, where the auteur and the blockbuster aligned, are more revealing of cultural conditions than the unique genius of the three men in question. And while the promised technological revolution might have come to moviemaking, it will be a long time before we fully understand what it’s done to movie watching, with unpromising early returns. No amount of technical wizardry or bankrolling can force art down a society’s throat. Because ultimately, the missing factor in any structural assessment of what Hollywood does, or does not, do, is taste. And right now, society is facing a life-threatening deficit.

Derek Robertson is a writer based in New York.