Midway through The Beast in Me, Netflix’s entertainingly flawed saga of murder and longform journalism, comes a moment guaranteed to make the editors in the audience smile. Nile Jarvis, a menacing real estate developer played by Matthew Rhys, has recently snuck into the home of Aggie Wiggs (Claire Danes), the author writing his profile. Coming behind her subject, Aggie discovers not thievery but a manuscript full of notes. “The Beast and Me”? Try “in.” Et voilà! A middling “4” of a title is now a solid “9” or “10.”

Netflix’s limited series is not quite an exploration of writing and revision. One could be forgiven, however, for noting how often the sociopathic Nile improves our heroine’s work. When viewers first meet Aggie, a neurotic scribbler of New Yorker dreck, she is struggling through a book-length tribute to Antonin Scalia and Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s friendship. Oh, barf. Mere days later, the Pulitzer winner has set aside that pedantry in favor of a snazzier job. “You should write about me,” Nile remarks upon realizing that he and Aggie are new neighbors. Indeed, she should. The dramatic arc is much more compelling.

Nile’s story concerns the disappearance and likely death of his first wife, a crime for which he has already been convicted in the court of public opinion. Determined to build Jarvis Yards, a mixed-use venture on the banks of the Hudson, Nile wants nothing so much as to be “relegitimized” by a major journalist. For her own part, Aggie is in no position to refuse her neighbor’s offer of “access.” A bereaved mother, she can’t forgive — and torments — the young man whose poor driving took her son’s life. Perhaps this will be the book to bring her back from the personal and professional brink.

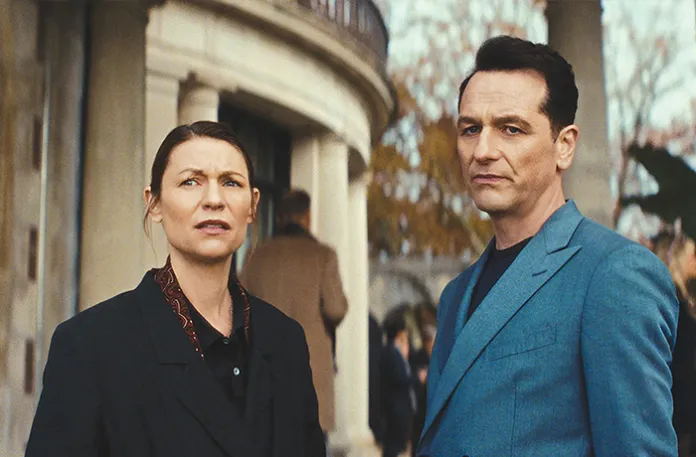

Such tawdry motives are hardly the stuff to make Walter Cronkite stand up from his grave and cheer. What they can produce, if the actors are capable, is abundant fireworks. The hugely talented star of FX’s The Americans (2013-18), Rhys is more than up to the task, imbuing Nile with a smiling ferocity just this side of deranged. In his best-known role, the Welshman played Philip Jennings, a KGB officer under deep cover as a Washington, D.C., travel agent and father of two. Here, the actor evokes a different kind of sleeper hiding in plain sight. Nile appears, at a glance, to be entirely guilty. But wouldn’t an actual murderer take care not to seem so obviously a villain?

As for the production’s supporting players, they are uniformly well-cast and effective. Fresh from Netflix’s The Hunting Wives, former soap star Brittany Snow is quietly charismatic as Nina, Nile’s second and current wife. Jonathan Banks (Better Call Saul) is characteristically strong as Nile’s father, Martin, a man whose incompletely buried conscience provides one of the show’s few points of authentic moral concern. Best of all by far is Deirdre O’Connell (The Penguin) as Aggie’s agent, a performance that manages to summon every literary representative I’ve ever met without descending into cliché. Though it might be going too far to ask that O’Connell receive her own spinoff series, her dishy, unsentimental work steals every episode in which she appears.

If I am delaying a particular verdict, it is only because the actress in question has been so good across her more than three decades onscreen. In My So-Called Life (1994-95), Danes achieved a poignancy of expression that remains the teen-angst standard to this day, despite numerous pretenders to the throne. Homeland (2011-20), in its early seasons a revelation, was as perfect a marriage of material and dramatic lead as the medium has yet produced. Watching The Beast in Me, one could almost wish that Danes had retired at the end of her 96 episodes as troubled CIA operative Carrie Mathison. What happened instead is simply sad. Danes’s latest work is not just underwhelming but an outright, even a spectacular, disaster.

How that came to pass is worth a moment’s thought. A performer of exceptional technical skill, Danes has long possessed near-perfect control over the muscles of her face. If a scene calls for vulnerability, she will deliver it with a precision that awes. The problem is that, having dipped into this bag so frequently, Danes is increasingly unable to modulate her grimaces and tics. Take, for example, her infamously quivering chin. (Google it.) The same gesture now emerges whether the actress is going over Niagara Falls in a barrel or settling for her second-favorite Château Lafite.

One consequence of this indiscrimination is that Danes has become more than a little tedious to watch. We know already the mannerisms with which she will advance the emotional plot. Another is that, paired with a naturalistic actor such as Rhys, Danes can appear to be playing to the back row rather than to the camera mere inches away. One might expect, given his showier role, that Danes’s co-star would be the one to chew Netflix’s scenery. Sorry, no. Rhys is clearly having a wonderful time and gives a memorable, if broad, performance as a man content to be a brute. It is Danes who leaves teeth marks. The beast in me, indeed.

Does a disappointing co-lead ruin an otherwise juicy series? In this case, at least, I think not. Although few will look to the production as a model of psychological realism and restraint, the show is so much fun scene by scene that one is inclined to forgive it its faults. Hey, you: Want to watch a rich monster build skyscrapers while whiners pound sand? I thought so.

Graham Hillard is editor at the James G. Martin Center for Academic Renewal and a Washington Examiner magazine contributing writer.